Me Too

I enjoyed the “Ice and Flying Don’t Mix” article in the January issue. It was right in line with a recent experience I had near Philadelphia.

Harry Dill

I bought my 2003 Ovation a couple years ago primarily for its flight in known ice certification (FIKI). Frequent trips to the Milwaukee and Philadelphia areas to see grandkids mean occasional exposure to ice. I’d never flown with FIKI. My first use last year was very encouraging; climbing out of KUES through an icy layer into the clear we accumulated maybe 1/8″ on the landing lights and wing tips but nothing anywhere else. However, I subsequently found and fixed multiple fitting leaks.

Two weeks ago I planned a flight into Brandywine, PA (KOQN) from our home field near Raleigh, NC (5NC5). Weather conditions got extra attention as the forecast indicated overcast ceilings at around 3000 feet with tops at 9000 and a cirrus layer at 25,000; temperature from the ground up was below freezing. There were AIRMETs for moderate ice.

After 40+ years of reading about bad outcomes when challenging ice I was a little nervous about this trip. On the other hand, a descent from above the tops to clear air below was what the Mooney’s TKS system was certified to do. Plan B was to return if the ice was prohibitive.

Taking off we climbed through a thin broken layer and were then VMC up to 9000, our final altitude. As we approached an undercast, the pitot heat came on, the TKS system was primed and indicated successful pressurization.

Then came a descent clearance to 4000—just below the ceilings. I switched the TKS to MAX and began descent. We started picking up ice on the leading edge of the wings almost immediately. My attention now focused on the TKS system operation and ice buildup while the autopilot kept us on course and in the descent at 700 fpm. Descent speed was kept high to preclude the autopilot getting us into a stall condition.

I reported moderate ice (AIM says I should have said severe). By the time we broke out at 4000 about eight minutes later there was at least inch of ice across the entire leading edge of both wings.

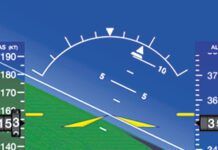

Over the next few minutes the TKS system seemed to catch up and most of the ice broke off the leading edges. The TKS system appeared to be working, just not keeping up with the rate of accumulation, but when we landed there was still ice on the outboard 10 inches of the right wing. (See the photo.)

Lesson learned; checking the TKS system during runup is not sufficient. I need to ensure that fluid is flowing freely down the entire length of each panel. I suspect that not all fluid was reaching the panels with some leaking out of the fittings. The plane goes into maintenance next week for an exhaustive check on the TKS. I’m hoping the service center will find and fix a problem. Otherwise, it will be difficult to trust the system; even for brief ice exposures (which is all I would ever use it for).

Harry Dill

Mebane, NC

Thanks for the story, Harry. Hope by now you’ve regained confidence in your system.

“No” to Privatized ATC

While I agree that privatizing ATC in this country would be the final nail in the coffin of GA, I’m not sure Nav Canada is an argument for the proponents.

I took extended trips in Western and Central Canada from 1996 to 2011, and I can say service was never very good. Typical wait times for IFR clearances were 45 minutes from filing to receipt, and it wasn’t because they were swamped with flights.

Harry Dill

I don’t know how it is now, but in those days a pop-up clearance was not gonna happen—land somewhere, try to find a phone (cell service in those days was abysmal), call in and you’d get the clearance, eventually.

A briefing once failed to elicit the NOTAM that my CANPASS airport was closed by an airshow to all VFR traffic, and I was issued a clearance for 15,000 feet (in my non-turbo 182).

Canada really didn’t seem interested in piston singles flying IFR. I don’t know if that’s changed or not; I avoid it now whenever I can. I note also, that U.S. ATC and the new, improved EAPIS don’t play well together, either, at least for GA.

On the positive side, the very reasonable charge (seems like it was under $20 U.S.) for quarterly use of their services was at least manageable. I expect when—not if—our ATC is finally privatized, the charges will be that much per flight or more. Canada can’t afford to get rid of GA because their huge empty spaces make it a necessity. The U.S., however, doesn’t really seem to need or want us.

David T. Chuljian

Port Townsend, WA

What Maintenance?

I found one comment in your March article, “Manage Your Electrons” to be confusing. You said that Concorde batteries “require ongoing care in the form of keeping them charged…”

There wasn’t any content in the article that fleshed that out, but “require” is a strong word. I know some people use the chargers he was referring to, but what’s the evidence for them? Are they required?

Andrew Doorey

Wilmington, DE

Okay, “require” is perhaps a bit strong. If battery longevity isn’t a concern, or if your aircraft gets flown every few days, then, no, you probably don’t need a battery charger/maintainer/desulfator. However, if battery longevity is important to you and you don’t fly as often as needed to keep the battery from sulfating, then, yes, you really should be using the recommended battery charger/maintainer/desulfator. More information is available in the follow-on article, “Inside Batteries” that appeared in May.The battery in my Cessna 340 is now up over $700. I purchased a new battery a number of years ago and did not properly maintain it. After less than two years, it was junk. I replaced it and spent the requisite few hundred dollars on the proper charger/maintainer/desulfator and that replacement battery is still going strong after four years. Clearly, this is anecdotal evidence, but I urge you to research this with both Concorde and with BatteryMinder for more scientific evidence.When I’m on a trip, I don’t worry about the battery because I am flying every few days. But, as soon as the plane is securely put to bed in the hangar, I plug in the BatteryMinder and walk away with confidence that the battery will be strong and ready for my next flight, be it in a few days or a month or more. —FB

ATC Knows

I enjoyed your December article, “Altimeters on Approach“. But in the article, you left out one other possibility in an emergency. If you cannot get the altimeter setting for your destination and cannot get it for any surrounding airports or any of the other ways you mentioned, you could ask ATC for your indicated altitude and use that to set the altimeter in a Part 91 flight emergency. Assuming your encoder is within limits—which it should be—that would also give you a guesstimate to which you could add a safety factor.

I love the publication and a month never goes by that I don’t learn something or am forced to think more deeply about certain situations.

Larry Levin

Lincoln, RI

You’re right; we didn’t consider that.Our Mode C is based only on pressure altitude (29.92) and ATC computers display your altitude after adjustment for local baro settings. But, they don’t have magic sources; if you can’t get the altimeter setting, ATC can’t get it either. However, it’s reasonable to assume that those same computers will smooth the readout based on outlying altimeters, similar to what we suggested you do manually. Thus, the accuracy of that setting might be no better than other things you could do.Also, recall that Mode C only resolves to 100 feet. So, ATC will see your altitude as, say, 3300 feet and the next thing they see is 3200 feet. Even if you have a 10-foot or even one-foot encoder, the Mode C format only sends 100s of feet.With some time and some effort you could reduce that uncertainty from 100 feet to perhaps as little as 20 feet or so. Start a very gradual, smooth descent and ask the controller to tell you the instant the readout changes from, say, 3300 to 3200 feet. In a perfect world, it should make that change at 3250 feet. Given the inevitable lag for processing time, reaction time, radar sweeps, etc., I’d probably set my altimeter to indicate about 3230 feet when the controller reported seeing 3200 feet.Like the article, this is an intellectual discussion with unlikely practical application. Given all that extra time and effort, we’d just go to another airport. Recall that the original discussion surrounded an emergency requiring nearly an immediate landing. Nonetheless, you’ve offered yet another way to think this through. Thanks for thinking outside the box.

We read ’em all and try to answer most e-mail, but it can take a month or more. Please be sure to include your full name and location. Contact us at[email protected].