Airborne communications failures can be uncomfortable at best. It’s eerie hearing the radios go quiet when they should be bustling with transmissions, and you can’t tell anyone about your plight. It gets even worse when it’s a sign of something more serious, like an electrical system failure.

It’s here where you must let good judgment do the talking instead. Your actions going forward will define the difference between a positive or problematic outcome.

For us on the air traffic control side of things, the biggest issue is predicting what an incommunicado pilot will do next. Some pilots do what they’re expected to do. Others go off the rails, piling on the anxiety. How did different pilots—including yours truly—react when their talk boxes tapped out?

Is Anyone Home?

Many years ago, before I became an air traffic controller, I rented a Cessna 172 and flew VFR over to an airport just over an hour away. On the return flight, I hit some turbulence. While getting whacked around, I dialed in my home tower’s frequency on COM1.

When I transmitted a request for landing, though, I heard only silence. It was the middle of a weekend day at a busy Class D training airport. No chance the pattern could be this dead. I checked the frequency, headset jack, electrical system, and volume. All looked fine. I transmitted again. Nothing.

Well then…. I eyed the light gun signal chart on my kneeboard and reached to squawk 7600: radio failure. Then I realized I had one last thing to check: the COM buttons. And there it was! In the turbulence, I’d accidentally bumped the panel and set COM2 as my receiver, while leaving COM1 as my transmitter. I set COM1 to transmit and receive, and suddenly my headset burst to life with ATC and aircraft transmissions.

Tower had been hearing me the whole time. He wasn’t too pleased, as I’d been stomping on his own transmissions and his traffic’s calls with my (unknowingly) blind transmissions. However, he’d heard my intentions, spotted me on his radar, had his light gun prepped, and was going to make a gap for me. Even if my low-time butt hadn’t solved the puzzle, he had a pretty good idea of what I wanted.

While not exactly an Apollo 12 “SCE to AUX” story (Search the web for it.) this was an early lesson to me on the importance of knowing your aircraft’s systems. Also, that sinking feeling of being incommunicado taught me something else: I needed to buy a handheld backup radio, and I did.

Mutual Surprise

Even with a backup radio, though, things can go awry. One day in a previous tower, I was working Ground. My friend was training a new controller on Local (Tower). The trainee was struggling a bit with the pattern and sequence. While handling my own duties, I was acting as a third pair of eyes, ensuring things didn’t get too out of hand.

Along with several training aircraft in the downwinds, I knew they had two trainers on final. But, something looked odd. I snatched the binoculars and saw… a third aircraft! A glance at the radar confirmed a dim primary-only target between the two trainers. “Hey,” I asked my friend, “does N123AB have a wingman?” Uh, no? “Then who’s that Cherokee right behind him?”

My friend immediately took over the position from her trainee and broke the lead aircraft out of the way. Not knowing who this guy was or what he was doing, she moved her downwinds further out. I grabbed the light gun and gave the Piper a steady green. It was easier to get him down, than to keep maneuvering our other planes around him indefinitely.

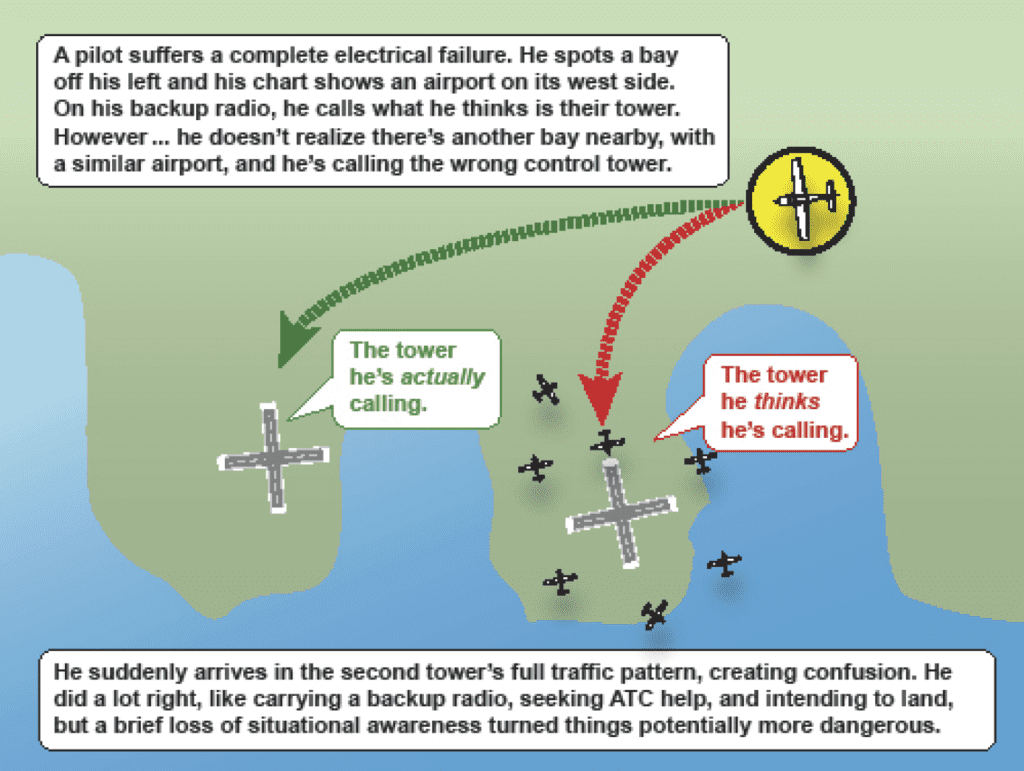

After he landed safely and taxied in, we advised the FBO to have the pilot call us. He told us he’d been flying VFR on his own and had a complete electrical failure 15 miles north of us. He got out his chart and portable radio, and took a look around. Off his left, he could see a large bay. On his chart, there was an airport on the west side of that bay, so he dialed in that tower’s freq on the portable and told them the situation.

All well and good, except he missed a key detail: there were two different bays in the region… and each had an airport similarly located on its west side. While he was talking to the other tower, he was in fact approaching ours. As he got closer and lower to us, he dropped below radio coverage with the other tower, who was trying to figure out where he was. However, through luck, he just happened to fall into our traffic sequence perfectly.

An initially confusing situation had a good resolution. He’d seen my green light gun signal and knew somebody—even though it turned out I was a different somebody—was looking out for him. The lesson here is: even when encountering communications difficulty, try to maintain situational awareness, lest you make things inadvertently worse and your luck doesn’t hold up.

Want a Wingman?

Aircraft lose communications with ATC fairly often. It’s not uncommon for me to see a couple during an average shift, usually VFR trainers on cross-country flights. Maybe a frequency change got missed or misheard.

The other day, a center controller handed me off a VFR Skyhawk inbound to one of our satellite airports and told me he’d lost comms with it. I typed “RF”—radio failure—and clicked on the target, making a bright red “RF” appear on the target to every controller in our airspace. I then called the destination airport’s tower, told him the situation, and he said he’d let me know if the Skyhawk contacted him. A few minutes later, he called me back; the Skyhawk had indeed checked in with him. He landed normally. Situation over.

Like this, nine out of ten times, an airplane’s ventures into Frequency Land get resolved benignly. If the airplane keeps doing what’s expected of it—in this case, continuing inbound to its destination—and every controller involved is in on the situation, it’s no sweat.

However, in this post-9/11 world, the red flags start waving when an aircraft—especially an IFR one—does something completely unexpected. Over two decades ago, it was controllers watching multiple IFR aircraft veer off course and refuse to respond who first knew something was horribly wrong on that September day.

One afternoon, Center called our approach control with a concerning situation. An IFR light twin had been filed to a towered airport 60 miles south of our airspace, lost comms, got near its destination (its clearance limit), and suddenly turned north, directly at us. Center reached out to it on Guard 121.5 and other frequencies. No joy. They were still receiving its transponder, so the aircraft had electrical power.

Per 14 CFR §91.185 (IFR operations: Two-way Radio Communications Failure) if the pilot was in VFR conditions, he should’ve landed “as soon as practicable.” If unable to proceed VFR, he should’ve continued via “the route assigned in the last ATC clearance received” and—upon arriving at the clearance limit—then “proceed to a fix from which an approach begins and commence descent or descent and approach as close as possible to the estimated time of arrival.”

This fellow didn’t do any of those things. He didn’t land when the issue first occurred. He then just blew right on past his clearance limit. ATC didn’t know if he’d been incapacitated or was up to something nefarious. We take this stuff seriously, moving our traffic out of his (unpredictable) path, alerting the towers in the area, and continually reaching out to him on Guard and our standard freqs. He also remained on his original IFR code. Squawking 7600 (communications failure) would’ve indicated he was aware of his communications status.

Suddenly, long after he’d entered our airspace, he just nonchalantly called us. When told Center had been trying to reach him, he said he’d lost comms with them and—you could almost hear the shrug on the radio—decided to change his destination to an airport in our airspace. That’s not how that works, sir, I felt like saying.

A controller cleared him to his new destination, but also gave him the “Possible pilot deviation…” phraseology, with Center’s phone number. The willful violation of his clearance limit was truly concerning. Had he just landed where expected, it would’ve been a non-issue. Instead, Center had already been making calls to scramble some F-16 fighters from a nearby US Air Force base to get eyes on him. That was certainly going to be a fun phone conversation. The last I heard of the incident, we’d sent the investigators our radar and radio recordings.

Study in Contrast

Not long after the previous incident occurred, Center called us with yet another IFR NORDO—“no radio”—aircraft handoff. The whole radar room groaned. However, this time, it was as if the universe was trying to balance itself. The pilot flying this Cherokee did everything by the book.

The pilot’s clearance limit was an airport within our airspace. He arrived in our space, squawking 7600, indicating he was aware of his comms failure. He flew the route he’d been issued, steadily trucking along at the filed altitude of 5000 feet. There was an overcast at 3000 feet, which would hamper any attempt to proceed and land VFR. We kept other aircraft away from him and flagged his target with an “RF.” As before, we notified the control tower.

Once he was in the vicinity of his clearance limit airport, the Cherokee turned a downwind leg and started a descent. He levelled at 2000. When we pulled up the RNAV Runway 9 approach map on our scopes, we could see he was overflying its left initial approach fix, whose altitude was—you guessed it—2000 feet. He crossed the IAF, flew towards the intermediate fix, and then departed it towards the final approach fix.

Once he was in the vicinity of his clearance limit airport, the Cherokee turned a downwind leg and started a descent. He levelled at 2000. When we pulled up the RNAV Runway 9 approach map on our scopes, we could see he was overflying its left initial approach fix, whose altitude was—you guessed it—2000 feet. He crossed the IAF, flew towards the intermediate fix, and then departed it towards the final approach fix.

Just then, the tower controller rang. “Approach, Tower, N123AB just called me on his handheld radio. Partial panel failure. He’s got the airport in sight.” We authorized the tower to clear him for a visual approach, and the Cherokee landed safely. We notified Center as well. There likely wouldn’t be much paperwork to do here; it was a non-incident, as the pilot did everything he should’ve done.

ATC works aircraft based on their known intentions. When radios fail and ATC can’t ask you, the pilot, to verify those intentions, the only things ATC can fall back on are your filed flight plan and the Radio Communications Failure guidance in §91.185. That’s not the time you want to go off the rails and pour on more unpredictability.

Good decision making going forward can make the huge difference between a benign radio failure situation—like the latter situation with the Cherokee—and a surprise-formation-flight-with-an-F-16-type incident. Stick to the plan as best as you can, and ATC will provide the space and assistance you need.

Tarrance Kramer appreciates the benefits of fully functional radios while working air traffic out in the Midwest.