Special Use Airspace often must be avoided, but what if you need to cross military airways, or even fly into a Military Operations Area? Lots of GA destinations exist in such airspaces, and it’s certainly legal to fly within most, even when active. So when fuel’s tight and weather’s chasing you to an unknown destination, it should be like any other flight—with additional FYIs.

Goin’ Direct

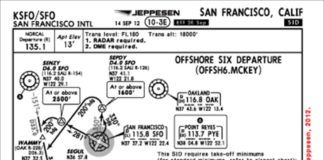

For this personal trip from southern Minnesota to central Texas, there will be at least one, maybe two, fuel stops. Wanting to get as far south as possible before stopping, the first destination is Ponca City in northern Oklahoma. That’s a convenient stop with reasonable fuel prices (relatively speaking, in this year of record-high fuel prices).

It’ll be a leg-cramping 3.5 hour flight even going fast. Still, your Hershey-bar Piper with 50 gallons will arrive with an hour reserve. With convective weather intensifying to the south, you want to get an early start noting you’ll land sooner if needed to avoid bad weather.

While you haven’t yet flown to Oklahoma or Texas, you start over familiar territory as you make your way direct from Redwood Falls, Minnesota, (RWF) to KPNC. So you’re good with flying right through the Crypt North, Central and South MOAs.

While these large MOAs are active from 8000 to 17999 feet regularly during the week, there’s a long break each day from 1101 to 1359. Since you’ll be motoring through under IFR between 1230 and 1330, you’re good to go, and before departing RWF get “cleared as filed” for 10,000 feet. There have been other days when you’d have to either fly lower or bypass the MOAs to the west. But today, you’re happy with the direct route—any fuel saved will provide better reserves for reaching Ponca City.

The other lucky break is that the straight line to KPNC shoots between the Eureka and Riley MOAs and even avoids a Restricted Area around Manhattan, Kansas. However, there are numerous Military Training Routes, depicted as light brown airways on the en-route charts, that zigzag across your route. They include VR 540 (which you cross twice), IR504, VR535, VR511/512, VR534/535. What about those?

MTR Review

Shouldn’t be a big deal, as flying IFR provides the same traffic separation and advisories with military aircraft. The extra precautions come with speed (they get to fly faster than we can) and operations (they can do things we can’t). Aside from that, there’s more than you need to know about MTRs in the Chart User’s Guide, the Pilot-Controller Glossary (PCG), and the AIM.

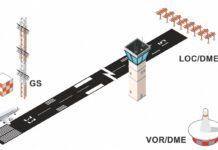

The chart guide, reminds us these follow a 56-day update cycle and notes that usually VFR Military Training Routes, “VR,” have four-digit numbers and users operate at or below 1500 feet AGL. IFR routes, with three or fewer digits, are labeled IR or VR and go higher. Like any other airspace or chart feature, you’ll find unique variations and MTRs have plenty.

The PCG (the latest found online via FAA Air Traffic Publications) describes IRs and VRs as having a lot of overlap. Both are routes “used by the Department of Defense and associated Reserve and Air Guard units for the purpose of conducting low-altitude navigation and tactical training” for IR (both IFR/VFR) or VFR, all “below 10,000 feet MSL at airspeeds in excess of 250 knots IAS.” The lengthy MTR entry in AIM 3-5-1 adds a reminder that like MOAs, Restricted Areas and such, any number of military activities can cross your flight route. In general, MTR widths run from four to 16 miles and if you have a concern, ATC can pass on information for routes in their sectors.

That’s easier than following the AIM and contacting FSS. Or if you’re bored, there’s a military pub referred to in the AIM as the FLIP AP/1B. In the end, the guidance confirms that you can treat them much like MOAs. It’s legal to fly within an MTR and you probably often cross them without noticing. IFR traffic advisories are provided, but as always keep a watch on the airspace.

Now Off-Route

Loaded with more than you wanted to know about military airways, you depart for Ponca City with a close eye on weather forming to your right. The bulk of it seems to be moving more to the north, which will likely allow you to cruise well south and east of it. That and the oodles of alternates on the route near Omaha, Manhattan, and Wichita areas are reassuring. Given that, you’re fine with getting as far south as you can for the day.

Nearly three hours later you’re past Wichita and see a tail on the south end of the storm front starting to build to your right. NEXRAD shows a trend for the worse as it’s changing color while traveling directly east, towards you. Options: Turn around and land at a satellite airport near Wichita, or fly west now to get around the back of the building weather, then go back towards Ponca City.

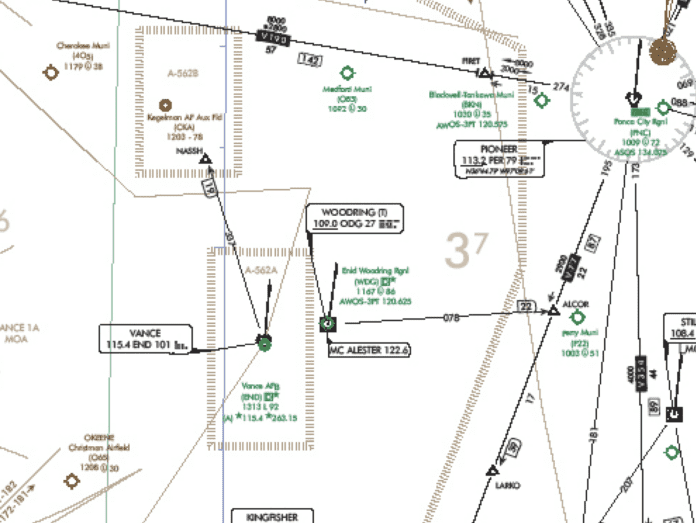

With scattered rain to fly through, but a wide enough gap of about 75 miles to avoid the heavier precip, you request and receive a big course change to the right. Now heading more southwest-bound with a good visual on the weather, everything’s calmed down. Except ATC gives you a heads-up that to descend to 6000 feet to get below the Vance MOA, northwest of the storms.

No problem, but you must remain clear of Alert Areas A-562B and A-562A. Do you want a new course around them? You look at the chart. That would involve using distances on radials from the Vance VORTAC, as there are no fixes, much less civilian airways, in the area to use. Yes, you know how to draw radials from a fix on the GPS, but it’ll take some button-pushing. Then you check the fuel situation, which is not in your favor. With 45 minutes remaining, you’ve gotta go somewhere practical.

Tight Squeeze

There are other tiny, unlabeled, airport-like symbols scattered around the region you’ve never noticed before; what are those? Tapping on one west of KPNC, you see it’s a VFR airport, 2K1, with one turf and one asphalt runway. 1OK has a 2540 foot turf runway. In an emergency, sure, but you’d prefer asphalt with runway numbers, and an approach would sure help.

Moderate rain is bringing the in-flight visibility to four miles, and low scud is forming below you. You hadn’t considered KWDG (Enid, Oklahoma) due to its location within the Vance 1B MOA, but it seems like the most efficient route to a safe landing. Chart check: it’s a Class D airspace situated just east of the sizeable Vance MOAs and even overlaps an embedded Alert Area, which notes “high density student training” up to 10,000 feet.

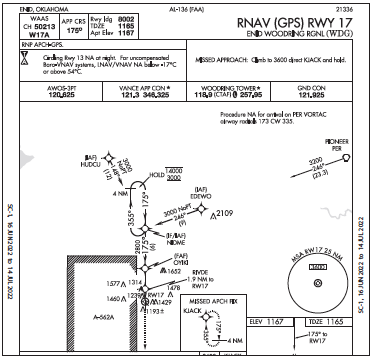

You want to go straight south to pick up the RNAV 17 at HUDCU, thus staying just outside military airspace. But the weather’s swirling towards HUDCU and to get behind the storms, the bargain with ATC comes down to vectors straight south around A-562B, then straight east between the two Alert Areas towards the NIDME IF/IAF as a start to a straight-in for 17.

With a south wind and your willingness to slow to 100 knots (saving a bit more fuel), the 90-degree turn to final isn’t a big deal right now. Besides, it’d also be a 90-degree turn to pick up the course reversal, and you certainly don’t need the additional time in the air.

Given a descent from 10,000 feet to 5000, you press on through a broken layer and look for the ground. The Enid AWOS indicates scattered clouds at 2000 feet with light rain and five miles’ visibility. That allows for VMC by the final fix. Lucky day, for sure: You had a straight-line route through lots of military airspace and almost made it to the destination; not bad considering the weather. Better yet, the fuel was cheaper at Enid.