Periodically, NASA’s Aviation Safety Reporting System publishes many of the most meaningful ASRS report submissions that relate to various specific aspects of aviation, such as weather, near-midairs, GPS and the like. We looked at these selected reports covering Air Traffic Control, with a view toward lessons we can learn in dealing with ATC, better practices we can follow, and generally ways to do things better.

You’ll note two recurring themes. The first is incorrect pilot readbacks of controller instructions and controllers not catching the mistake. The second is pilots turning incorrectly left, right or to the wrong heading, or similar errors with altitude, as in this first case below.

Descend via Canceled?

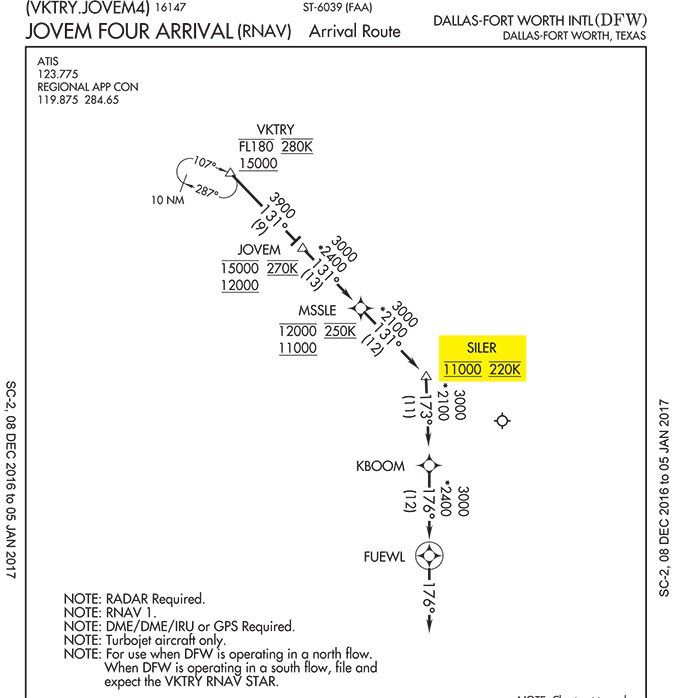

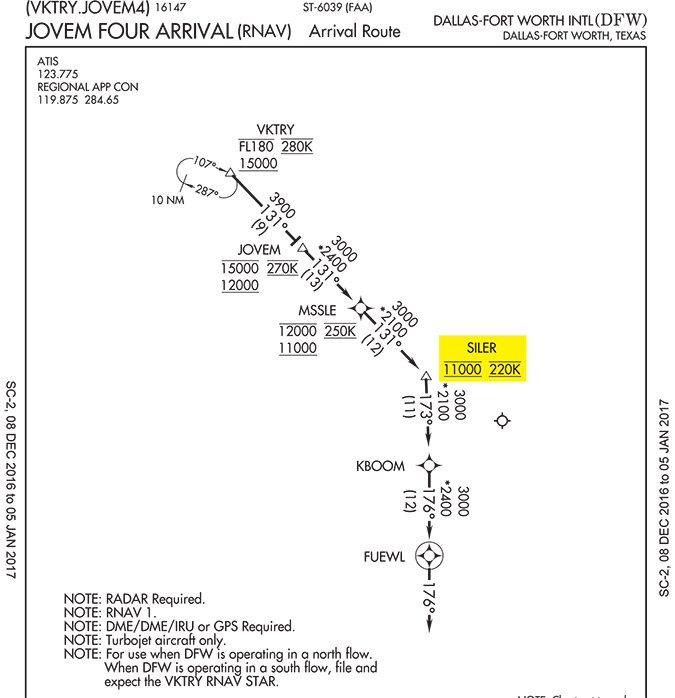

Fort Worth Center told an aircraft to descend via the JOVEM2 [now JOVEM4] arrival, level off at 6000 and contact Regional Approach as they descended through 7800 ft. The receiving controller questioned their altitude, having expected them to cross SILER at 11,000 feet as published. In the receiving controller’s view, they had descended early. The descending aircraft informed approach that the last center controller issued the descent.

In the future, the captain said that if told to descend to a lower than published altitude he would not descend until he confirms with ATC that the descend-via clearance is cancelled. This error resulted from not clearly understanding the clearance and could have been remedied with a clarification. When in doubt, ask.

Bad Place for a Jump Zone

An approach controller told a jump aircraft to cross an intersection at 14,000 feet so he could work other aircraft down on the arrival. The jump pilot thought he was cleared to 12,000 feet and read that back, garbled but readable. The controller did not catch the incorrect readback. That lower, incorrect altitude complicated matters for arrivals in progress.

In this case, the pilot erred in reading back an incorrect altitude and the controller did not catch the error. The matter became critical because the jump aircraft was descending along a busy arrival route into a major airport.

Dark Territory at SFO

An aircraft was instructed to line up and wait on Runway 10L. The crew properly acknowledged. The flight was then cleared for takeoff. There was no acknowledgement and the aircraft didn’t move. The instruction was issued again with no response from the aircraft. Tower then canceled the takeoff clearance and directed hold in position. Still, there was no response. ATC switched to the standby transmitter, told the crew to hold in position and asked how they heard. They reported loud and clear. There is a dead zone on Runway 10L and elsewhere where aircraft of certain height are unable to receive the tower’s main transmitter.

This is also a common problem at many GA nontowered airports. At North Palm Beach County (F45) for example, Clearance Delivery is the issue because the radio is off-airport. Sometimes moving an aircraft just a few feet solves the problem. In aircraft with one antenna atop the fuselage and another below, the top antenna will usually work better. If nothing works, you can call FSS for your clearance or call the Clearance Delivery telephone number at (888)766-8267, or even depart VFR and get your clearance airborne.

NORDO No-No

The weather at SFO was very bad when they lost radio contact with an IFR corporate aircraft west-southwest of SFO at an unknown altitude. The airport was using Runways 10R and 19R for departures and there were aircraft in position. The SFO tower manager suggested that they taxi those aircraft clear of the runways in case the subject aircraft was more than just no-radio (NORDO), but also had an emergency and was trying to land at SFO. This foresight proved wise when the aircraft emerged from the clouds and landed on Runway 1L, opposite the traffic flow for the airport and with a tailwind exceeding 20 knots.

If NORDO, the pilot should have squawked 7600, or in an emergency, 7700. This would have helped the controllers understand the nature of the pilot’s issue. It did not help that aircraft’s altitude reporting system was malfunctioning.

The aircraft’s destination was nearby. Under 91.185, the pilot should have landed there, but in an emergency it could land anywhere. The pilot’s actions were erratic and seemed panicky and you just can’t help wondering whether the pilot’s skills were up to the nasty weather that day.

Uh, Your Other Right

A Jacksonville controller issued traffic to a military transport, calling out a southbound VFR aircraft at the same altitude. The controller advised the transport that on their current heading, the VFR traffic would pass close behind, but if the transport turned 15 degrees right, the traffic would definitely pass behind. The transport acknowledged, “Looking for traffic.”

Mistiming is everything. The controller was then to be relieved. Subsequently, the transport reported that traffic had come within 20 feet of him. The controller then noticed that the transport had incorrectly turned left changing course toward the traffic, not right, away from the traffic, as advised.

In retrospect, the controller felt he should have reissued the traffic to make sure the transport saw the traffic. Alternatively, he could have issued a positive-control instruction instead of a suggested heading. It might also have been wise to delay the relief briefing until the traffic was clear. As always, the pilot who confused left with right should have confirmed the turn if there was any doubt as to which way to turn.

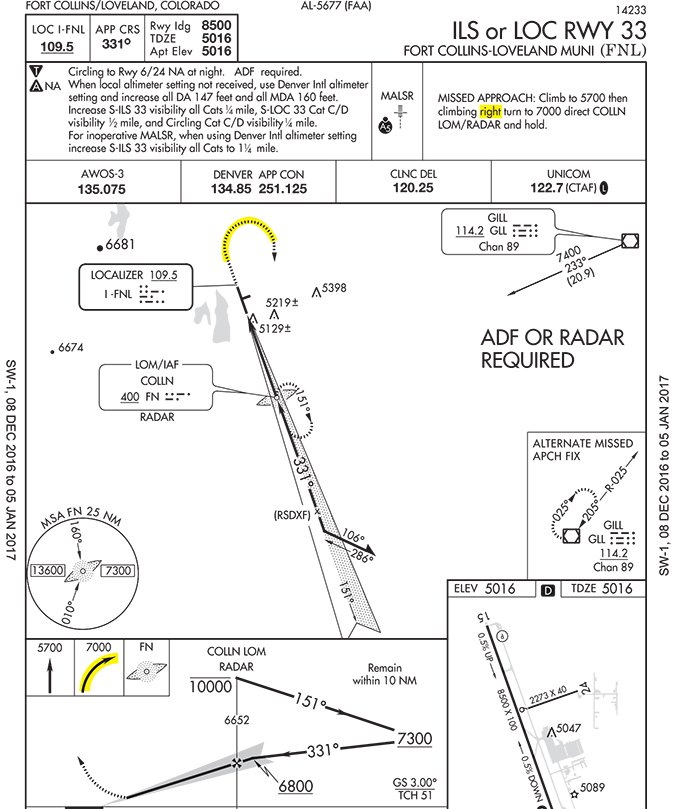

Heading Disconnect at KFNL

Fort Collins-Loveland Municipal Airport is nontowered and has a Diverse Vector Area (DVA) from 350-180 degrees. The main runways at KFNL are 15/33. Standard Operating Procedures state that Runway 33 departures must be issued a right turn into the DVA and the controller must hear it read back.

Controllers there have requested management to explain why the DVA only begins at 350 degrees and what pilots must do to get there because Runway 33 is published with left traffic. One controller had an IFR aircraft shooting a practice ILS 33 at FNL. The controller issued missed approach instructions—a right turn to 120 degrees—and the pilot read them back correctly.

Observing the pilot’s missed approach, the controller saw the aircraft turn left and check in on a 190-degree heading, below the 7000-foot minimum vectoring altitude (MVA) and entering an 8000-foot MVA. When the controller inquired about the original clearance the pilot said he had to comply with the left pattern and was now turning left to the original 120-degree heading. That would have made matters worse by pointing back toward a busy traffic pattern and going even deeper into a higher MVA—a significant safety risk.

The pilot seriously erred because he neither followed ATC’s missed approach instructions nor the published missed approach instructions, which also call for a right turn. There is no requirement to “comply with the pattern.” The pilot was at greater risk as he turned left and then further left back into the pattern, now facing oncoming downwind traffic. Had he turned right to 120 degrees on climbout, there would have been no conflicts with the pattern on the left.

Getting into the DVA arc is possible and legal if the missed approach instructions are followed. We can assume that the contradiction between the controller’s instructions and the published traffic pattern direction would at least have created some confusion in the cockpit. Need we say it again? When in doubt, ask.

Trust, But Verify

A Seattle Center controller issued an IFR clearance via Victor 4 and a descent clearance. The pilot read back the clearance. The MEA on the airway was above the altitude issued in the descent clearance. Hence, the descent clearance should not have been issued, but rather a climb clearance to the MEA. The TRACON caught the error and the controller then issued correct instructions.

Our trust in ATC is well-deserved, but even they make mistakes. The crew should have verified the MEA for themselves. When a descent clearance is issued, it’s a good idea to satisfy yourself that you’re not being descended into something solid.

Snowballing Emergencies

An IFR corporate jet was inbound to Fargo, ND. Icing was present at all altitudes. The aircraft was at 2800 feet MSL with a reported airport ceiling of 700 feet AGL. It was daytime.

The pilot reported an autopilot issue which he later reported resolved. On the vector for the ILS, the pilot reported an engine failure. Given the aircraft’s position, a turn close to the approach gate (about two miles outside the FAF) was going to be required. The aircraft was unable to join the localizer and become established. ATC suggested a second try, but as the aircraft was joining the localizer it took a turn due west and again flew through the localizer. ATC speculated that the autopilot problem was perhaps not resolved after all.

The third time, ATC changed the game and asked the pilot if he wanted an ASR (Airport Surveillance Radar) approach. This time the pilot was vectored out onto a five-mile final, descended, broke out at 1800 feet and landed safely.

Very few of us have ever flown an ASR approach, even a simulated one. Airports that offer them are found in the Chart Supplement. If it has an ASR approach it will be noted in bold at the very bottom of the listing. You can find a complete listing of all radar approaches in section N of any Terminal Procedures Publication.

Most ASR approaches are found at military airports, but not all. KFAR has one, as does KCRG in Jacksonville, FL.

Too Much Turn

Northwest-bound Aircraft X lost cabin pressure and began a descent from FL240 without clearance. Just then, aircraft Y was climbing through 15,000 for FL230. The controller stopped aircraft Y’s climb at FL180 and told him to turn to 240 degrees and then issued FL190 to aircraft X. As aircraft X neared FL190, the controller noted that aircraft Y had turned not to 240 degrees, but 140 degrees, having misheard the instruction. The controller then told aircraft Y to turn to 220 degrees for traffic. During this turn, IFR separation was lost.

It is amazing how quickly things can get ugly. This is just one example of many pilots who misheard altitude and heading assignments. In some cases the controller missed the incorrect or an incomplete readback, as in the next report.

What You Think You Heard

An aircraft departed Fairbanks, Alaska on an IFR flight plan. The controller issued, “reaching 3000 feet, turn right direct airport ZZZ.” The pilot read back, “Roger coming right direct ZZZ.” The pilot did not acknowledge the altitude restriction, nor did ATC catch it until the aircraft was about 1.5 NM west of the departure corridor and climbing through 1700 ft. The controller realized what had happened, and asked the aircraft, “Aircraft X, verify heading 200.” The aircraft responded, “Negative, we are heading 297 direct ZZZ.” The controller then asked if the aircraft could maintain its own terrain and obstacle clearance, because he was now in an area with a 3700 feet minimum vectoring altitude. The pilot responded, “Affirmative.” The aircraft was then issued its clearance and after reaching 3700 feet was cleared as filed.

The error was not just the pilot’s. The controller admitted that “expectation bias” was a major factor, and he thought he heard what he expected to hear.

High Flyin’ Drone

An air carrier flight climbing through 6500 feet from Charlotte, NC encountered a drone about 2000 feet below the aircraft in the Class B airspace. No evasive action was required.

“Small” drones (55 pounds and below) should remain below 400 feet AGL. How anyone could control one at 4500 feet is a mystery, assuming it was under control at all.

The ASRS filer hit the nail on the head: “Not sure what the FAA can do about this problem.” Drone manufacturers must be required to build machines incapable of flight above their legal ceiling and entering hazardous areas to aircraft, called “geofencing.” For now, vigilance is our only recourse.

In sum, listen carefully when ATC gives you instructions. Read them back carefully and completely. Avoid turning the wrong way. Be especially mindful of altitude assignments including subtle modifiers such as “reaching.” Oh, and when in doubt, ask.

Fred Simonds, CFII tries to be diligent in radio usage and vigilant for traffic, especially those pesky little UAVs.