Simple in principle, procedure turns can turn ugly if the pilot and the controller aren’t on the same page. GPS has made this worse, not better. But that’s easily remedied.

It used to be the procedure turn (PT) was the lynchpin of many an instrument approach. You’d track to the VOR or NDB station located on the airport, fly outbound, use a PT to reverse course, and fly back to the station on a specific course while descending to the specified minimum descent altitude. If you didn’t visually acquire the airport, locating the missed approach point was a simple matter of identifying station passage.

These approaches still exist, but the advent of DME and GPS have made them the exception rather than the rule. Yet the PT lives on. It’s time to get the rust off your PT flying skills, bend that GPS receiver to meet your will, and ensure that you and air traffic control understand the game plan.

Right Tool for the Job

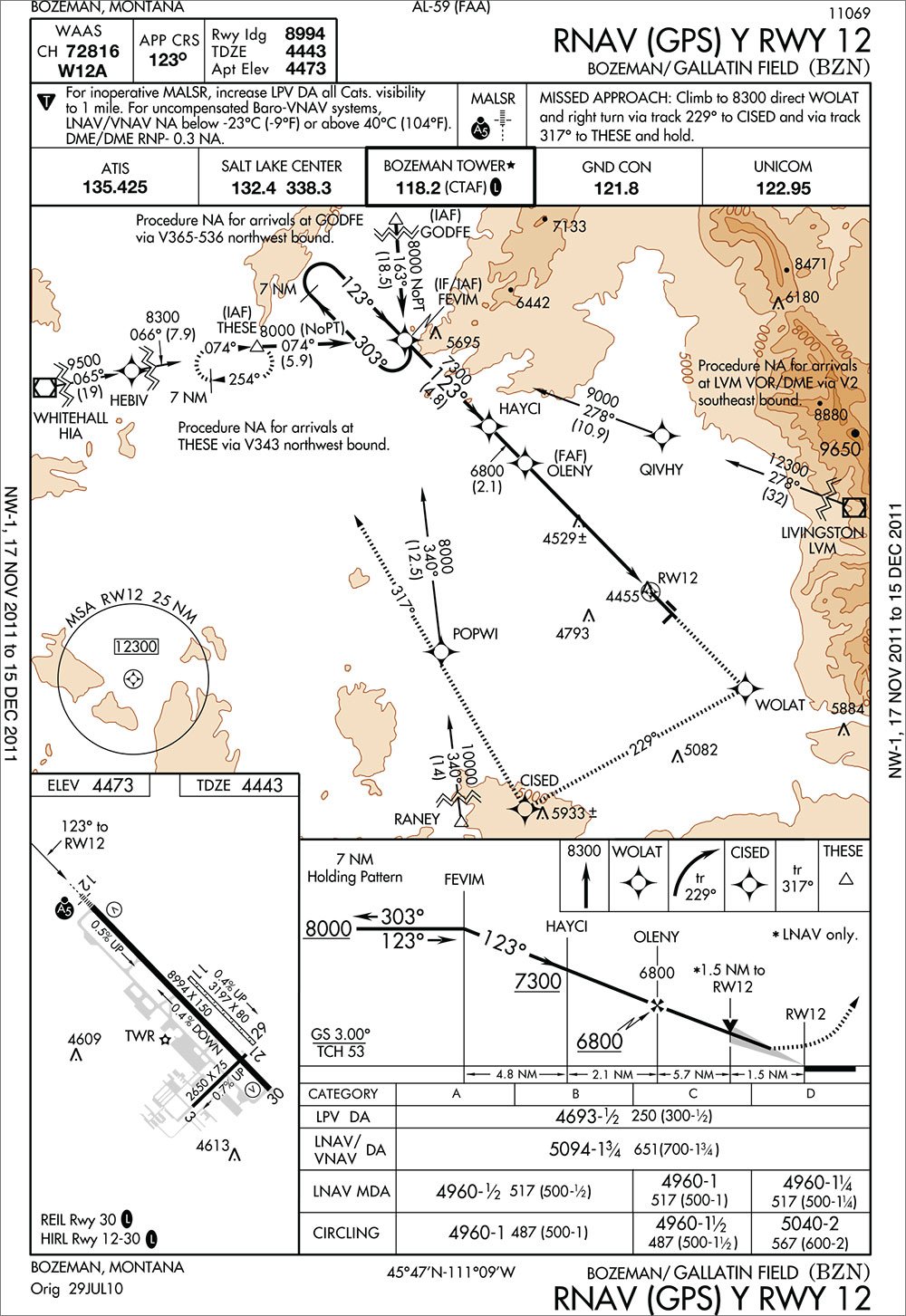

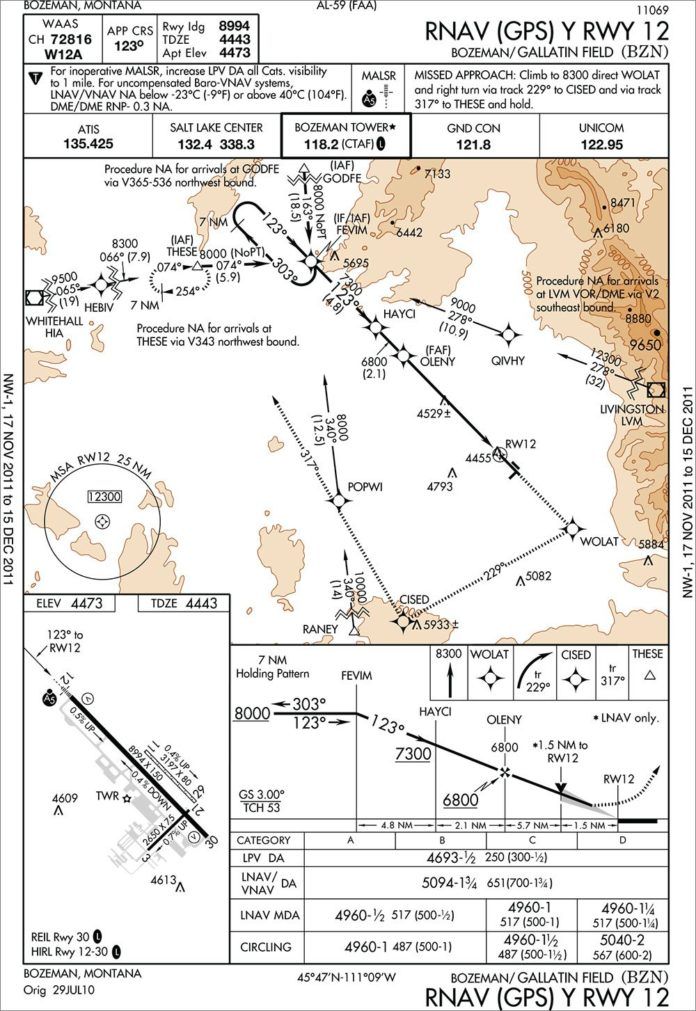

PTs come in three flavors: The barb, the teardrop, and the hold-in-lieu of procedure-turn. However you fly it, a PT is a controlled maneuver allowing you to change direction, often while climbing or descending. The profile view on an instrument approach will specify the altitude to maintain and the distance you must remain within while reversing course.

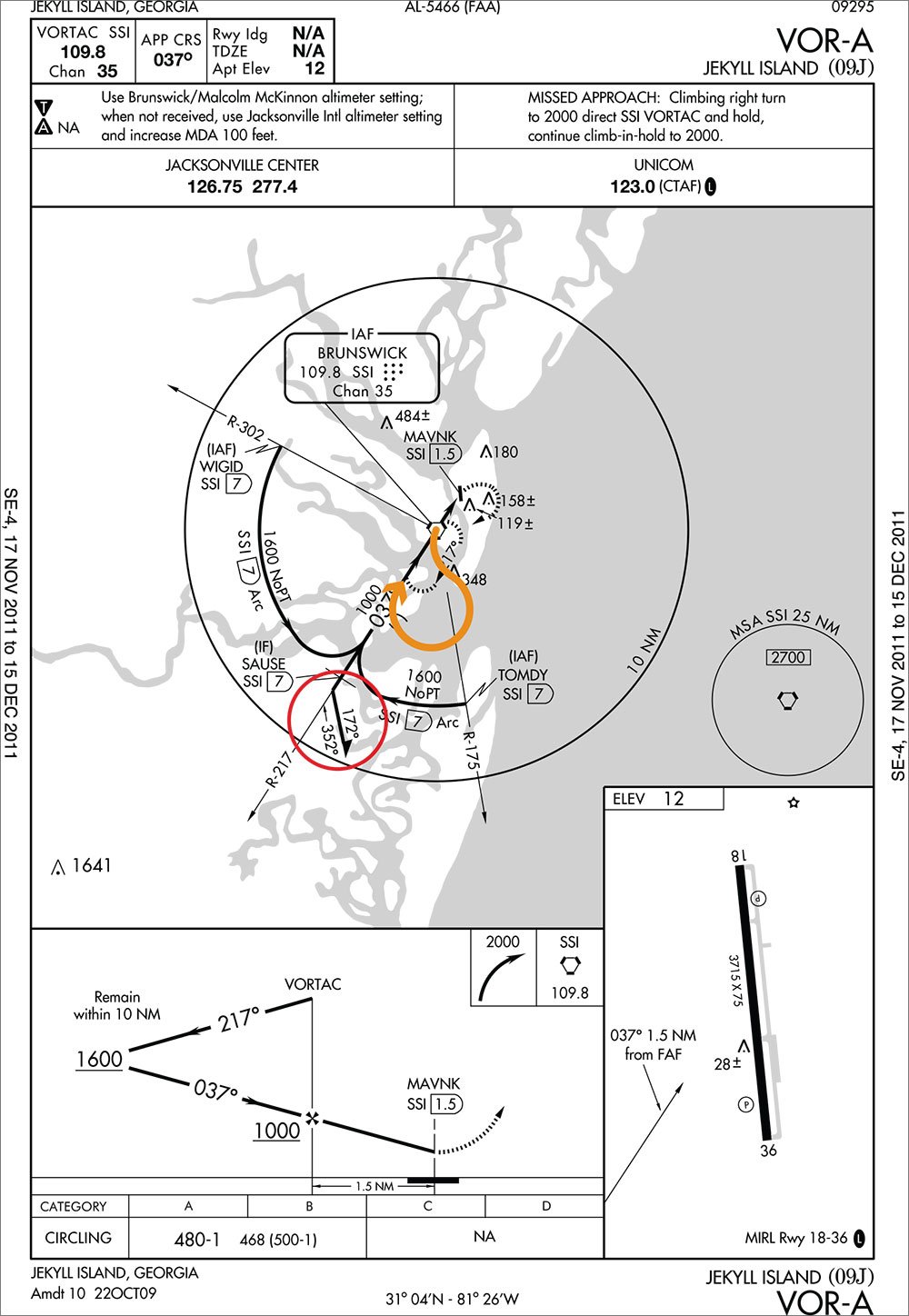

The most common PT depiction on the plan view of approaches based on ground stations is the barb. It’s also the most flexible; you can reverse course however you like as long as you maneuver on the same side of the approach course as the barb depiction.

The standard technique is to turn 45-degrees in the direction of the barb, fly for a minute, do a standard-rate 180-degree turn and intercept the inbound course. Depending on the winds, this should take about three minutes. GPS receivers like the G1000 will prompt you to fly the 45-degree PT, but you have other options.

If weather is approaching, you’re low on fuel, or there’s some pressing need, you can fly the 80-260: Turn 80 degrees in the direction of the barb depiction, then immediately roll into an opposite turn of 260 degrees and intercept the inbound course.

The 80-260 is more abrupt and you’d be wise to practice first with an instructor or safety pilot before attempting it in IMC. The 80-260 PT takes about two minutes to complete and is a good technique when time is of the essence. Your GPS receiver should figure out you’ve turned inbound, but be prepared to activate the appropriate leg or waypoint should it become confused.

The teardrop PT is another option. Cross the appropriate fix outbound and then turn 10, 20 or 30 degrees; just be sure you’re maneuvering on the same side as the barb depicted on the plan view. If you turned 10 degrees, fly outbound for three minutes (two minutes if you turned 20 degrees or one minute if you turned 30 degrees) then turn inbound and intercept the inbound course.

Hello HILO

Last, but not least, is the holding pattern in lieu of a procedure turn, or HILO. (It’s probably better abbreviated as the HILOPT, but no one seems to do that. Maybe HILOPT sounds too much like you’re trying to spit out the horsefly you just accidently inhaled.)

When a hold is depicted for course reversal, you’re required to fly a holding pattern entry to reverse course. RNAV approaches commonly specify holding pattern leg lengths of four miles. For high-altitude airports, they can be as long as seven miles. Your GPS will dutifully guide you that full distance, burning more time and fuel in the course reversal than necessary for most light GA aircraft. If you want to fly a one-minute outbound leg, just ask ATC. The controller may actually prefer that you fly shorter legs. Such is the case with the Rio Vista RNAV Rwy 25 approach (not shown here): When flown in VFR conditions, four-mile legs in the hold at WAGER will likely put you underneath the parachute jump zone at the Lodi airport!

Traditionalist pilots might not want to hear this, but using GPS to enhance situational awareness on non-RNAV approaches is a good thing when it comes to flying procedure turns. If your GPS displays real-time winds aloft, by all means let that inform your decision of how long to fly outbound before beginning a 45-degree or 80-260 procedure turn. With strong winds aloft, it can be difficult or impossible to know if you are straying outside the “remain within” distance shown on the profile view without GPS, especially if that distance is specified from an NDB or locator outer marker.

Need to PT?

You’ve just been cleared direct to the initial approach fix (IAF) on an RNAV approach and have also been cleared for the approach. Thing is, there’s a HILO depicted at the IAF. When you select the approach, your GPS asks you if you want to hold at the IAF. You are not flying on a segment of the approach that says “No PT,” so do you fly the hold or not?

The regulations describing PT restrictions are found in a rather strange place: FAR 91.175: “Takeoff and Landing under IFR.” The meat of the rule is: In the case of a radar vector to a final approach course or fix, a timed approach from a holding fix, or an approach for which the procedure specifies ‘No PT,’ no pilot may make a procedure turn unless cleared to do so by ATC.

This has led to a lot of arguments about what does and does not constitute a radar vector. Controllers love the point-and-shoot nature of GPS direct to a fix and will use it in lieu of a vector on to the final approach course if it will safely accomplish the same thing. In this case, they should say something like “Cleared straight-in RNAV approach.” If that happens, don’t fly the hold.

If the controller didn’t specify straight-in in your approach clearance, cut the Gordian knot: Ask them if they want you to fly the hold. The answer will probably be “No,” but better to ask than to be given a phone number to call after you’ve landed.

When loading a non-RNAV approach, look closely and you may be surprised to see your GPS receiver has included a PT or HILO without asking you. The tip-offs are a depiction of the PT or HILO on the moving map and the hold or procedure turn appearing in the flight plan view. To get proper waypoint sequencing, you’ll need to remove the unwanted PT or HILO.

The other great thing about using the GPS moving map is that it takes much of the guesswork out of that 80-260 turn. As soon as you start the 260-degree turn back to the fix, you can watch the progress on the GPS and adjust your rate of turn to roll out right on target.

Stay Sharp

You might never have to fly a PT or HILO in our world of vectors, but a wise pilot practices for those times when radar vectors aren’t available. Stay proficient, practice and you’ll have no trouble enduring the … umm … barbs and HILOs of outrageous fortune.

Getting the GPS to hold

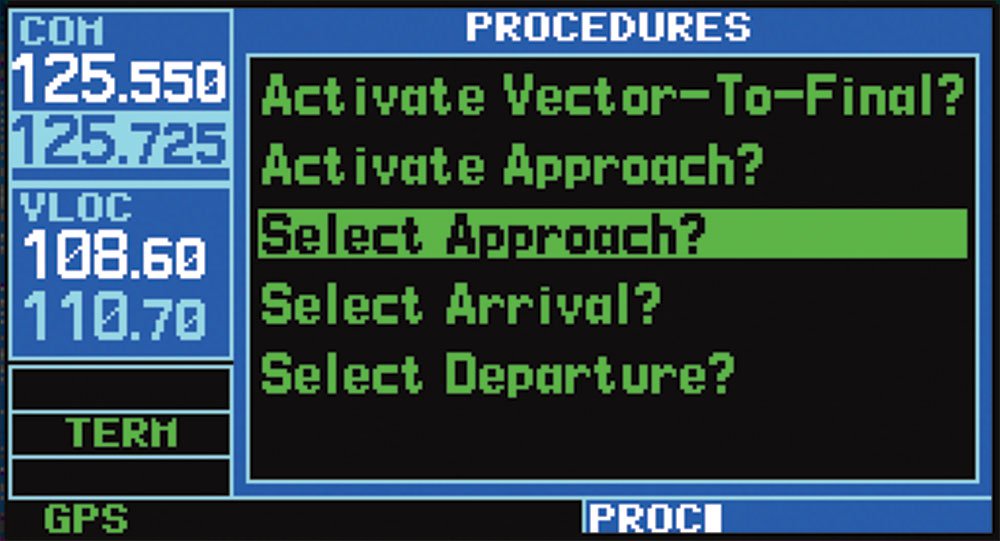

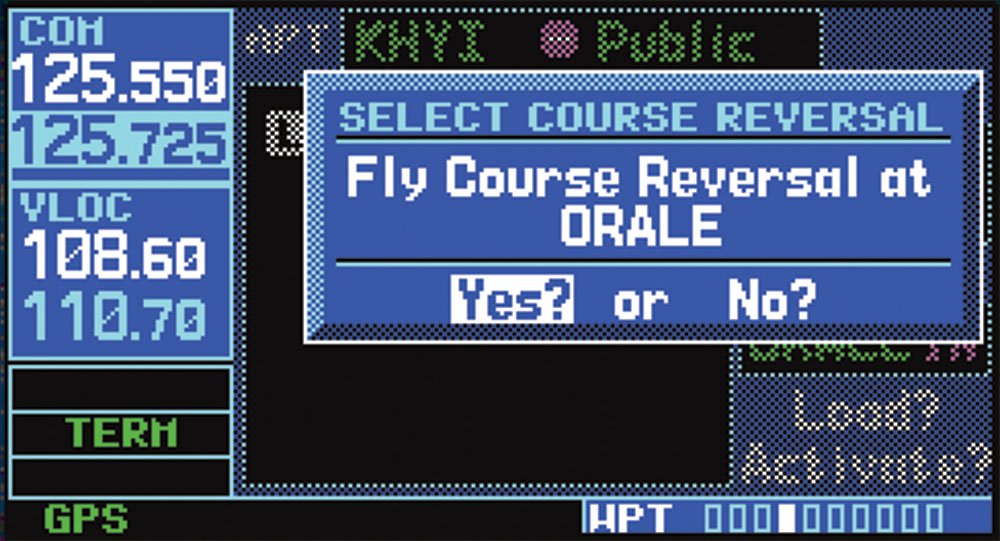

One issue for holding patterns for course reversals is getting the GPS to properly load the hold. Every unit is different, but the popular Garmin 400/500Ws and the G1000 behave similarly.

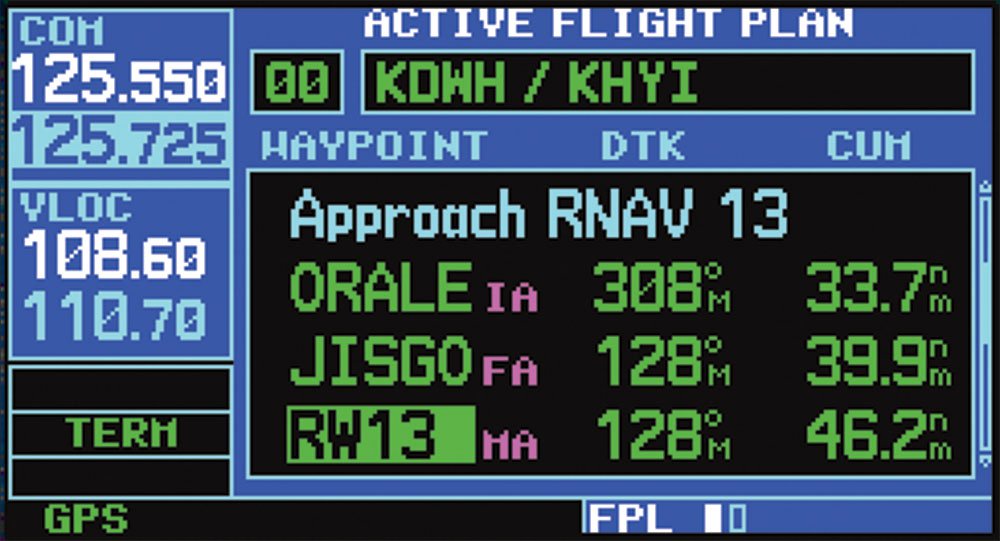

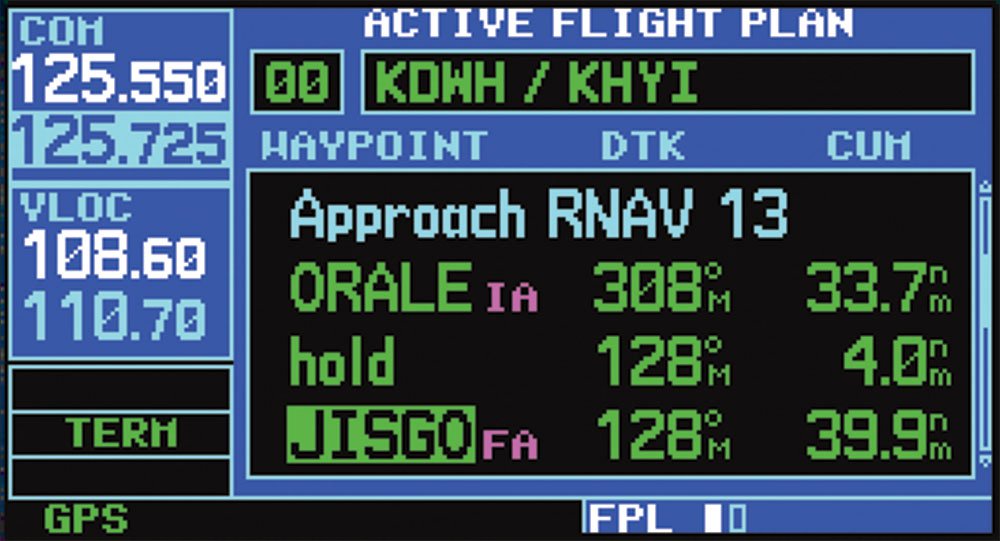

If you are approaching the hold from a position where you might want to be able to proceed straight-in, and you load the fix that defines the HILO as the initial approach fix, the GPS will ask whether or not you want to fly the course reversal. Select “Yes” and the hold will appear in the flight plan. Select “No” and the hold won’t.

That’s all well and good, until ATC tells you to expect that hold for traffic after you’ve already loaded the no-hold approach. There’s no way to just add it back into the flight plan. You’ll need to reload the approach from scratch and select “Yes” for the course reversal. Then when you’re in the hold, press OBS to suspend waypoint sequencing until you’re ready to move on.

Getting rid of a hold is easier. Get a cursor in the flight plan and scroll over the hold. Then push CLR. You’ll be prompted about removing the hold. Once it’s gone, you’d have to reload the approach to get it back.

You can also skip a hold by activating the leg just after it. However, make sure this won’t mess up any current navigation you have —JVW

John Ewing bears the whips and scorns of flight-training clients and blog readers in California. His blog is aviationmentor.blogspot.com.

Assume flying KCON-KCNH via KEYEK as IAF to RNAV 29, would you do the depicted lap in Hold as PT? (KCON is 24 nm from KEYEK)