Enduring a black-screen episode in flight, for those in the know, isn’t as bad as it sounds. While the thought of losing a moving color map is often the modern pilot’s horror-movie nightmare, most cockpits now have enough backup equipment so you can fly the airplane, navigate and (barring a full electrical failure) communicate. Do add a few essentials—a full array of charts, a good alternate, and a little recent practice. Then, you can make it out of the clouds, fly an approach and get on the ground without sweating, screaming, or going all white knuckles.

The Route

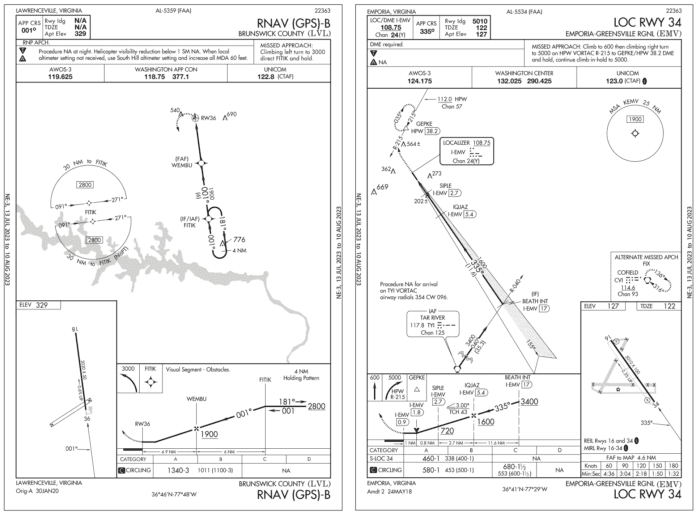

It all starts well planning your holiday weekend trip to Lawrenceville, Virginia. There’s a small airport with one 3020-foot runway (18/36). Sure, it’s small, but it’s minutes from your buddy’s house and a good thousand feet longer than your private turf strip at home in Georgia. You and your GPS-equipped taildragger will have a great time. Lawrenceville’s Brunswick County airport does have tie-downs and even instrument approaches (which you don’t have at home—yet). With marginal VFR in the forecast, the approaches to the paved runway will come in handy. You would’ve preferred using one of what seems to be two turf strips there, but those are marked closed. So the RNAV (GPS) A and B are available for 18 and 36, respectively.

According to the approach charts, the inbound courses are straight-in to each end, so why aren’t these named RNAV 18 and 36? Is the runway too short? Perhaps; it’s more common to see instrument runways at least 3500 feet. Mainly, it’s the lack of instrument-friendly markings, which here are sparse even by VFR standards. (See IFR August 2019, “Reading the Fine Print.”).The markings, as listed in the FAA airport data for 18/36, indicate the absence of runway end lights and it’s not clear of the status of other runway lighting. Markings are “basic” and their condition is “fair,” as is the asphalt.

Turning to the AIM, the term “visual” rather than “basic” is the lowest grade of three categories of markings. The runway will have numbers, maybe a centerline. Don’t expect glidepath guidance, lit or painted. Still, the weather’s nowhere close to low, so plan the RNAV B to Runway 36, published for 1340-3. The weather should hold around 2000-5, and you note that the MDA is a touch more than 1000 feet AGL so it just about matches the VFR traffic pattern altitude, offering a safe circling option if there’s a traffic conflict or if you need to go around. You can tie down for your weekend visit, and fuel up for the flight home.

Got Beacon?

The alternate will be a convenient one: Emporia, Virginia, is just a few minutes to the east. The only potential gotcha you see is winds—gusty from northeast and possibly reaching 25 knots. That could mean crosswind components bordering on your personal maximum of 15 knots. As winds at Emporia will be similar to Lawrenceville, you figure you can always cut the flight short and head for any number of airports along the way, many of which offer landings to the northeast. You’ll accept up to 30 knots for winds within five degrees of the runway. At Emporia, don’t worry about the LOC 34 chart that says “NA” for alternates, as the RNAV 34 lacks that limitation. You’ll use the LNAV approach as low as the MDA at 460 feet; the circling MDA is 100 feet higher.

On the afternoon of departure, you start the pre-flight briefings and see that winds in the area will persist at 25 knots from the northeast. By departure time two hours later, the latest report at LVL show 15 knots, so that gotcha is managed for the time being and you are prepared to make a landing decision on the approach. Winds aloft at 5000 feet, though, are stiffer than you expected, so after just an hour in cruise, you re-figure fuel reserves. The ETA of 4:40 p.m. local as originally planned now has you about 20 minutes behind. Continuing non-stop to Lawrenceville still meets your personal requirements to get all the way to Emporia with 45 minutes’ of fuel. But it’ll be close—50 minutes remaining, by your calculations.

With the sun starting to dip closer to the cloud tops as you cruise along, you now figure on a landing at dusk. On go the nav lights while you’re thinking of it, and definitely re-brief the IFR approach and plan to use it even after you have a visual on the runway. There should be plenty of ambient light remaining a few minutes past sunset. With several hours of night time logged recently, you’re still feeling okay with continuing. Now, local sunset time happens to be at 5 p.m. local this time of the month in November, but you never researched the exact time. You also don’t know until descending below the clouds on a ten-mile final that the airport’s lacking more than fancy approach lighting.

During planning, you checked the KLVL airport on the en-route chart and assumed by the tick-marked airport symbol there that it has services, mainly fuel. But unbeknownst to you, the VFR sectional shows no tick marks on the LVL airport symbol and correctly identifies this as a no-services field. You figure this out eventually using your EFB airport data.

Ironically, the longer-than-expected flight had you poking around more on your EFB. While still 50 miles from the airport, you realized that the approach is NA at night, and when you explore this in the airport data, there are blank boxes for features including runway beacon and fuel. Could that be right? Moments later you tap-and-zoom the Chart Supplement entry for Lawrenceville: “arpt clsd SS-SR indefly.” What the heck does that mean? It means ‘cause there’s no beacon and no runway lights, landing between sunset and sunrise is NA. Emporia it is.

Oh No, No Map

After getting a new route clearance from Washington Approach to KEMV, you pop in the approach and head to the new initial fix, RESTE, for the RNAV 34. You’re handed off to another Washington Approach frequency that’s on the approach chart, but you hadn’t expected a change so close to Lawrenceville. So when the touch-screen moving map blinks out, taking the radio display with it, you’re kinda stuck without the extra fingers or eyeballs to sort that out. What’s left for avionics?

There’s an early-version digital VOR/LOC tuner that’s running, but you haven’t used it in a couple years. You’ve got the tablet EFB, but it doesn’t have GPS. Gotta press on, so report your issues to the current controller, who can get you vectored in if you’re okay to navigate with what you have. Affirmative, but you want radar to confirm you cross the final fix. Done. You reduce power and lean the fuel as much as you can, reluctant to add low fuel to the workload. Diverting elsewhere really doesn’t enter your mind as that would mean flying after sunset and you just want to land.

Without a geo-referenced map and an old nav tuner, you realize it’s time to swap out for the LOC 34 chart. Then you see this approach has the same FAF (IQJAZ) as the RNAV 34, so you tune in the 40-degree radial from the Tar River navaid to back up your radar coverage, which will cease below 2200 feet. How else can you confirm position after the final fix?

The FAF-to-runway timetable, of course. Since that’s only provided on the LOC chart, not RNAV, you did need that chart after all. Approach also provides the latest METAR, allowing you to estimate a groundspeed of 60 knots and 4:36 to reach the runway from IQJAZ. From there, you break out of the last cloud and start the battery-powered digital timer that you smartly kept on the panel, and used often. The timing isn’t as crucial now, but you don’t have a way to turn on the runway lights and anything you have on hand is gonna be useful at dusk. Although the weather didn’t seem challenging starting out, that approach to Lawrenceville was best saved for a VFR day. And the alternate wasn’t ideal either, but sometimes the closest workable Plan B can be the best alternative.

Elaine Kauh is a CFII in eastern Wisconsin. Rendering moving maps inoperative during training flights is a specialty she enjoys just a little too much.