Encounters with low weather aren’t an everyday occurrence, but it just takes a tepid spring day to set the stage. Mix in moist, stable air, add a light aircraft and toss in a PIC with get-there-itis and you have it. So it should be no surprise for this flight to end well short of both destination and alternate, the latter just off the wing but out of reach. The only option is a far-flung diversion you’re not ready for. Better get started.

The Route

A family emergency is the only reason you decided to launch from St. Cloud, Minnesota (2000-10) for Dickinson, North Dakota (200-1). You’re flying a fast retrac and you’re well-versed flying in IMC; otherwise there’d be no choice but to sit it out or start driving. The LPV approaches at the destination also prompted the decision to go. The filed alternate is Bismarck, North Dakota, an hour east of Dickinson. It’s the closest airport that (barely) met the alternate weather requirements of 600-2 with an ILS approach. It also has a TAF, offering a means for monitoring local weather.

On the minus side, the three-hour, non-stop flight has little margin for delay if you divert from KDIK. While visibility’s expected to stay above one mile, ceilings are trending from 500-600 feet. And the AIRMET for icing conditions above 4000 feet, while north of your route, is a second factor to watch. The marginal VFR weather flying out of St. Cloud does allow for an easy return so long as, by your estimate, you turn back before passing Aberdeen, South Dakota, since the LIFR starts before the state line. Ice, a mechanical issue, or any glitch are all possible reasons to abort, so under the circumstances you feel like it’s get to Dickinson ASAP, or use your good turnaround plan.

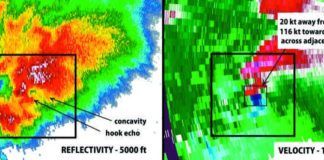

There’s no ice cruising at 8000 feet. Tops are higher than you thought, but the ride’s smooth so you stay at that altitude. Just short of Bismarck on V2, though, you hear pilots missing at both KDIK and KBIS. Conditions have dipped down to 100-½.

You’ve come this far, so the urge to get in somewhere as close as possible to Dickinson is strong. You decide to overfly both your airports to reach better weather to the west. Glendive, Montana is the best and nearest option, slightly better at 400-3. The LPV approach, by the numbers, will get you in with 2708-1. So you amend the clearance and press on. Out here, you’d prefer to stay on the airways for the published MEAs and better position reporting, but there’s no direct way to Glendive. You scramble to find the few fixes in the area to use: DIK V2 UMWEL FESTU V545 YAFLU.

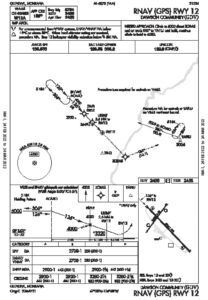

While a bit messy, Center’s got a couple of aircraft ahead of you also diverting there and the plan is to begin vectors to the approach as soon as traffic allows. You press on and read up on the LPV Runway 12. The plan view has two caveats for the arrival: “Procedure NA for arrivals at YAFLU on V545 northeast bound.” Not only is this the missed approach fix for the RNAV 12, it’s a 124-degree turn to pick up the transition to ACAKO. That’s past the maximum 90-degree turn for RNAV guidelines (See “A Bit Over Ninety,” IFR, September 2017). Your inquiry with Center assures you of vectors to ACAKO near YAFLU at an angle permitting the straight-in approach. Avoiding the hold-in-lieu-of-procedure-turn course reversal would still mean sacrificing fuel for a lengthy set of vectors, though.

Take the Hold

Here’s a novel idea: Fly the darn HILPT. It will save you time, distance and fuel over all that vectoring. Since you’re coming from the southeast, you tell Center you just want to get to ACAKO with the intention of flying the HILPT to the inbound course of 126 degrees. Sounds good; now you’re cleared from UMWEL direct YAFLU. Cross YAFLU at or above 6000, expect vectors from there. This you do, staying at 8000 for now. Four miles north of YAFLU, you don’t get the magic words, but something close: “Cleared direct ACAKO. Descend and maintain 5000. Report procedure turn inbound.” You make a beeline for the fix, then have a mental freeze: Where’s “procedure turn inbound”? Before ACAKO, or after? In the HILPT or on the 126-degree inbound? Not a good time to look that up, so … flip through the mental files and recall that this instruction means something more like: “Fly procedure turn then report inbound.” That’s where ATC will again assess the separation between you and the preceding aircraft.

But now you started accumulating light rime ice when you turned for ACAKO. Still at 8000; could 6000, or 5000, be better … or worse? You decide that altitude and speed are the priority. Reluctant to descend until the HILPT, you tell Center about the icing and the need for a block between 5000-8000 until “PT inbound.” Approved. Next, a sigh of relief and on to the hold. From the southeast it’s a teardrop entry at ACAKO. You’ve already slowed to 130 knots—15 knots faster than usual at this point. You don’t want to reduce that until the final segment of the approach. Now over ACAKO, you find yourself still at 8000 feet. You start a descent to 6000 feet on the autopilot, but you’ll still be high when entering the hold.

Worse, you didn’t tell ATC about a full lap around the holding pattern. AIM 5-4-9 is specific. After the holding entry, you’re expected to intercept final and head on in. “If pilots elect to make additional circuits to lose excessive altitude or to become better established on course, it is their responsibility to so advise ATC upon receipt of their approach clearance.” Well, technically, you didn’t receive this yet, so you request one circuit in the hold while descending to 6000 feet;. Approved, with a clearance for the approach, and “Report ACAKO inbound.” Still high, fast and clean (except for the ice), you turn within the holding pattern and now, in front of the southeast winds aloft, you’ve breached the pattern about a mile to the west.

Enter TERPS

Still high, you’re more concerned about ATC than obstacles, but there’s no comment other than “Roger” as you make you way back towards ACAKO and report inbound. With no more ice buildup, you decide to descend closer to the published stepdown. You’ll find out later that the IPH (4-46) confirms that a procedure turn primary area has at least 1000 feet of obstacle clearance. And: “In the secondary area, 500 feet of obstacle clearance is provided at the inner edge, tapering uniformly to 0 feet at the outer edge.” While its width doesn’t get a mention in the handbook, TERPS specifies that the secondary area is a 2-NM wide band surrounding the primary area.

Still high, you’re more concerned about ATC than obstacles, but there’s no comment other than “Roger” as you make you way back towards ACAKO and report inbound. With no more ice buildup, you decide to descend closer to the published stepdown. You’ll find out later that the IPH (4-46) confirms that a procedure turn primary area has at least 1000 feet of obstacle clearance. And: “In the secondary area, 500 feet of obstacle clearance is provided at the inner edge, tapering uniformly to 0 feet at the outer edge.” While its width doesn’t get a mention in the handbook, TERPS specifies that the secondary area is a 2-NM wide band surrounding the primary area.

Finally, you’re on the descent to 4000 and the glidepath leads you in with just one mile visibility, and bases at 700 feet AGL. This flight took closer to four hours due to the diversion, but it required just one approach and still left you with 45 minutes of fuel. You top off, wait an hour for Dickinson to improve, and pick up where you left off. While the diversion might not have been the best choice and icing made the get-there-itis worse, you had the mindset of focusing on the flying tasks (aviate, navigate, communicate), even if this flight wasn’t the best choice to begin with.