Until just recently, the role for most pilots was pilot flying with manual control, occasionally supplemented with autoflight when the workload was high and we needed a helping hand. With the increasing availability of more and more capable systems, that role is changing to one of systems manager or, worse, just systems observer. That’s not good. Our problem extends far beyond automation complacency. It’s become a new and dangerous way of thinking about the role of the pilot.

A friend of mine recently sent me a link to a rather lengthy YouTube video taken at an American Airlines training seminar called “Children of Magenta.” In this video, Captain Warren Vanderburgh gives an excellent presentation discussing issues that have long been on my mind. His cogent material allowed me to crystalize my own thinking and I’ve adapted some of his concepts to help convey my thoughts. My thanks to Captain Vanderburgh.

In the Old Days

When most of us started flying, you could certainly get an autopilot, and it could perform the wondrous job of keeping the wings level as you concentrated on more demanding tasks. If you had big bucks, your autopilot might even have the ability to track a VOR radial, although few of us actually used them that way because the signal from the VOR was too unstable and caused the autopilot to hunt.

Add a bit more capability (and money) and your autopilot would hold altitude with some precision and even level off at a preset altitude.

Once it could do all that, it was another step in money and electronic alchemy to have the autopilot fly an ILS. But all that’s been available for quite some time if you had the money. Few of us did have that money, or at least few of us chose to spend it on that stuff.

We could navigate from either NDBs or VORs, although even then NDBs were falling out of grace, in favor of the far more robust and simpler VOR navigation. Of course, in most of our planes each navigation source had a separate instrument that required a great deal of engagement from the pilot to actually interpret the data to properly fly the course. Some of us even spent significant sums for a horizontal situation indicator to simplify the interpretation of that VOR data.

But until the advent of glass panels and electronic “navigators” the most technologically sophisticated system still required the pilot to remain fully engaged, checking signal strength, tuning in the next station, changing course and monitoring progress on, you know, a map. In GA about the best you could do was fly for about 75 miles before you had to do something to keep the airplane going where you wanted it to go.

In the New Days

In many ways, even our basic GPS navigators today rival the capabilities of the most sophisticated flight management systems of 20 years ago. Today you can program your entire route of flight from the comfort of your hangar or even at home. Once you take off, you’ve but to press a couple buttons and you can follow the magenta line all the way to your destination, many hundreds of miles away. And you can do that without bothering with further navigation chores.

It’s that newfound navigation simplicity that has insidiously changed our way of thinking. We’ve become lazy. We no longer have to monitor our progress on the maps, checking distance to the next VOR, monitoring for the change-over points and MEA changes and tuning in the next station. While we were doing that, it was just natural to use those checkpoints to monitor our fuel and remind us to change tanks. We’ve now disengaged from the entire process, with nothing to do except miss a few radio calls while we’re worrying about the next playlist on the MP3 player.

A number of years ago this point was driven home for me. I was flying along in our Cessna 340 in the low flight levels and I heard a pop-up asking ATC for an instrument clearance to punch through some unexpected clouds. Naturally, one of the first questions the controller asked was position, to which the pop-up replied, “Uh, we’re showing about 320 miles west of San Antonio.” Gee, really?

Obviously this guy had programmed direct to San Antonio and relinquished further navigational awareness to the integrated circuits of his navigator operating in collusion with the satellites. The controller, also recognizing what was up, simply said to the pilot, “I’m unable an IFR clearance without a position using fixes closer to you.” Good for him.

Even the FAA has noticed. In early January, they issued a Safety Alert for Operators (SAFO 13002) discussing this very topic. They recommend a renewed emphasis on building and maintaining the manual skills necessary to operate a plane without the automation. “Continuous use of autoflight systems could lead to degradation of the pilot’s ability to quickly recover the aircraft from an undesired state.” In this usage, “undesired state” could be as simple as a bit off course or as dramatic as upside-down from a wake turbulence encounter with a heavy. SAFOs are targeted at air carriers and organized flight departments, but the material can apply to all of us.

That Paradigm Thing

This whole thing runs deeper than just automation complacency. It has become a way of thinking.

Until all this automation, in our mind’s eye we were still a pilot, operating an airplane, even utilizing some automation when available. Increasingly, we’ve surrendered that mindset of flying the airplane in favor of our automation.

Captain Vanderburgh talks about one revealing incident he witnessed that I’ve seen multiple times in my own flying. It could be anybody, anywhere, so long as the airplane is equipped with a suitable autopilot.

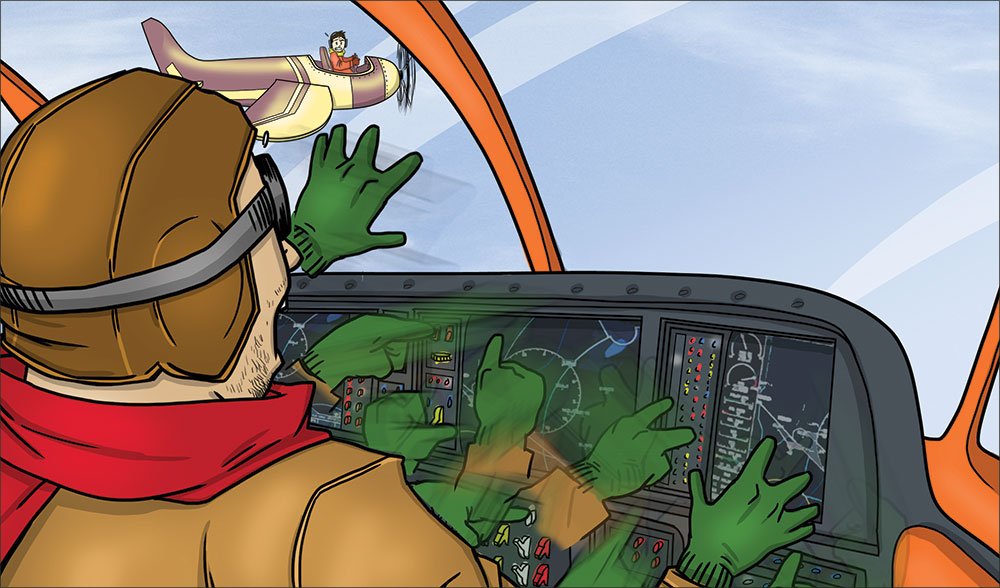

Our pilot, who has assimilated the automation paradigm in lieu of the more traditional pilot flying paradigm, has recently taken off and is in the climb. He spots crossing traffic in the distance, above him. Action is required by our pilot to avoid hitting the crossing traffic. There is sufficient time to make this a non-event, but little more.

Our friend frantically starts pushing buttons on the autopilot control panel, trying to get the plane to turn, level off or do anything to avoid hitting the target he’s rapidly approaching. The result is a near-collision with barely a hundred yards or so between the aircraft.

In his mind, the autopilot, not he, was in control of the airplane and he had to frantically instruct the autopilot to change the potentially cataclysmic trajectory into one that was merely breathtakingly scary. It simply never occurred to him to be the pilot flying and just push a button to turn off the autopilot and take manual control, giving the yoke a gentle push to reduce the climb and a gentle bank to pass a good mile behind and below the crossing traffic.

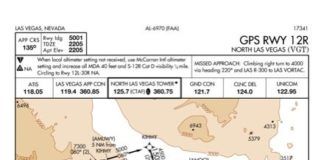

Consider being in busy airspace and the controller has his hands full. You’re already a couple dots high on the glideslope waiting for your clearance and just as you’re about to blow through final, you get, “Turn left, heading 300. Maintain 3000 until established on the localizer, cleared for the approach.”

Mashing all the right buttons will take at least 5 seconds, during which time you’ve traveled just enough further to give you no hope of intercepting before the localizer needle leaves the gauge. Instead, you can take less than a second to push the “A/P Disc” button on the yoke and immediately begin a somewhat steeper turn and descent, to cross the FAF exactly on profile.

To do that your hands must be in the right place. Are they safely in your lap, or resting lightly on the yoke, prepared to take control and fly your airplane at any time? Think about it.

Automation is a good thing. It improves safety, allowing us to concentrate on pressing matters without spending mind-share on heading and altitude. But we’ve got to guard against thinking of that automation as the primary controller of the airplane. After all, the FAA won’t bust your airplane for a violation. They’ll bust you.

It’s OK to Use Green Needles

The airplanes I fly for my day-job have a flight management system (FMS). Think of an FMS as little more than a navigation management system, similar to what our top-of-the-line GPS systems have become. An FMS, though, is able to automatically use all navigation sensors—VOR, DME, GPS and in many cases, even inertial navigation—to determine its position. The navigation capabilities and route management, though, are little different than what’s in today’s high-end GPS navigators.

As our fleet ages, the keypads on many of our FMSes are degrading and can get to a point where they just don’t work properly. The FMS is still usable, but you have to put up with an increasing and frustrating number of key input errors that really get in your way when time is tight.

So, sometimes enough is enough and the keypad gets so bad that I’ll defer it, forcing it to be repaired at some point soon. Because it is deferred, even though it’s still as usable as it was the moment before, we can’t legally continue to use it. We can fly without the FMS, but we then lose all that fancy point-to-point navigation and we’re limited to good old fashioned VOR/DME nav with charts and change-over points and all. That can be a handful for a leg or two, but it gets easy after a bit. I even had one FO tell me it was fun to fly “the old-fashioned way.” (Yeah, I had to let that one go.)

It usually takes a few days before the aircraft is routed back to a maintenance base for a new keypad. Meanwhile, many crews may have to fly it…on the green needles of VOR navigation. Occasionally, I’m one of those crews as I get swapped back into the plane another day.

In many cases, however, I notice that the deferral has been removed. Another crew was reluctant to fly on green needles so they simply called maintenance and told them the FMS was working “normally” and returned it to service. Perhaps that SAFO is right; maybe we have become too dependent on our automation. —FB.

Frank Bowlin actually enjoys hand-flying the airplane. Even so, he still must guard against slipping into the automation paradigm.