We’ve all heard “Maintain … until established.” We fly the route and make our descents without ATC yelling (usually). But are we actually doing it right?

Surprisingly, the FAA is not the place to look for a definition of “established.” The AIM and the Instrument Flying Handbook say nothing on the topic. Only in the Instrument Procedures Handbook (FAA-H-8261-1A) does a definition pop up, and it just says that ICAO defines “established” as within half-scale indication on a localizer or VOR course. Useful, but there must be more.

Vectors to Final

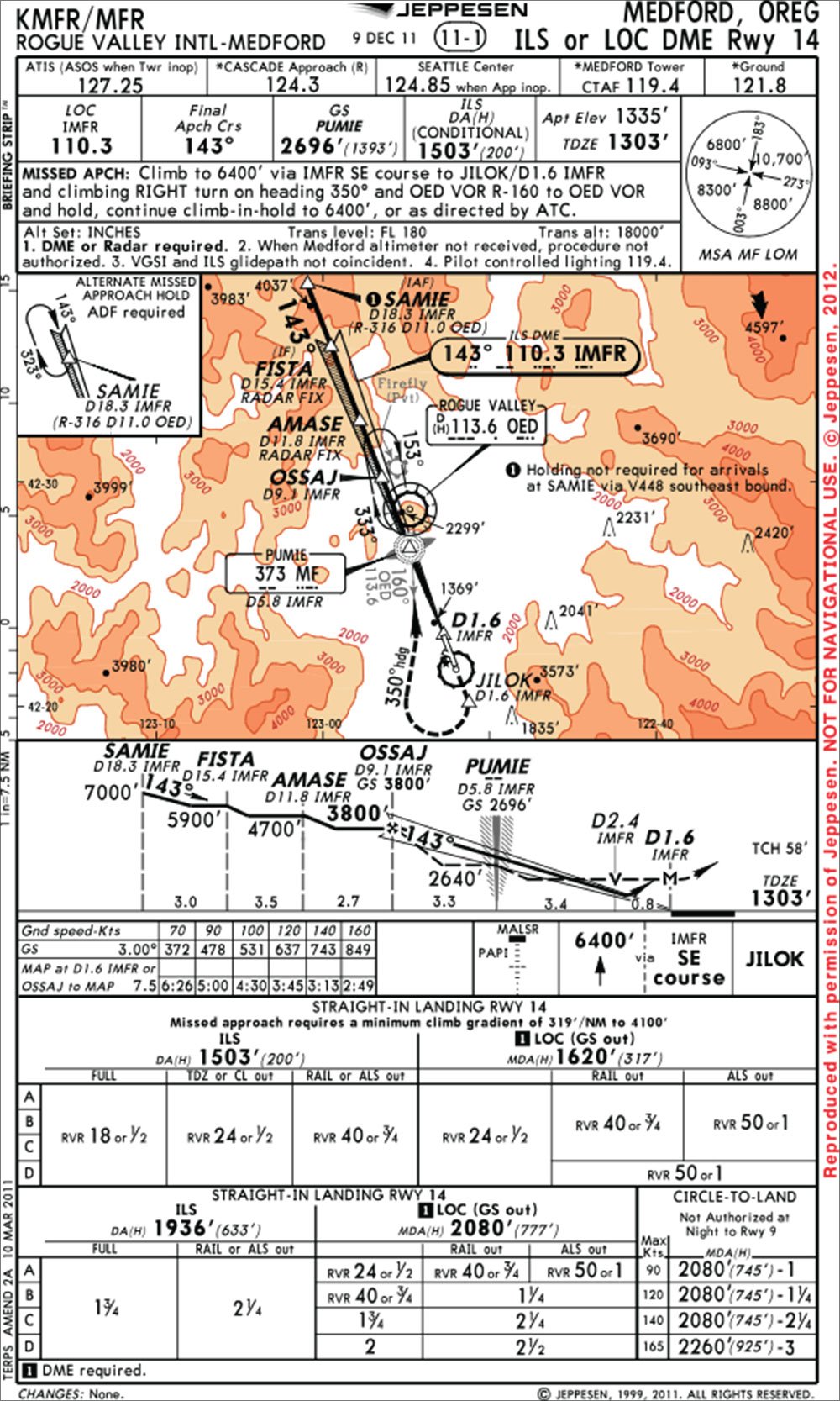

For “more,” let’s work our way through the various cases, starting with the simplest. Say you’re on a heading from the north into Medford, Ore., and you hear those empowering words, “Fly heading 180. Maintain at or above 7000 until established on the localizer. Cleared ILS Runway 14 approach.” If terrain permits, you might get, “Cross FISTA at or above 5900.” Just begin the turn and descent then level off on heading and altitude. Then wait until you’re “established.”

Eventually the localizer needle approaches half-scale. You turn and smoothly intercept final and note that you’re outside FISTA —textbook perfect for ICAO. Now what? Before we answer, let’s look at the “What if?” case of needing to descend more quickly.

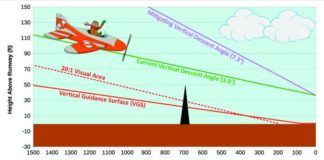

Recall that your CDI shows two degrees per dot. A five-dot instrument represents 10 degrees full-scale. A localizer increases sensitivity four times, so full-scale here is now only 2.5 degrees. Extrapolating from the old “one degree equals one mile at 60 miles,” that 1.25 degrees for half-scale at five miles is just over a tenth of a mile. Yet, the laterally protected airspace at five miles on an ILS is 5000 feet each side. So, you’d be quite safe using “course alive” as your definition of “established” if you needed a little extra time or distance—so long as you’re not on a checkride or anything.

Step Down

Outside FISTA at 7000 feet, the glideslope centers. Rather than bother with those step-downs, perhaps you should just ride the glideslope down. The FAA charts depict a continuous slope through the step-down fixes, which might mislead you into flying the glideslope from 7000 feet down. The glideslope doesn’t guarantee you’ll meet the minimum crossing altitudes at FISTA and AMASE. Atmospheric conditions can conspire to make the crossings at FISTA and AMASE higher than the glideslope by a hundred feet or more, and ATC might get testy about it. Jeppesen more clearly depicts the stepdowns as restrictions.

So you can ride the glideslope and monitor your compliance with the crossing restrictions, or you can dive-n-drive after each step until intercepting the glide slope at the FAF. Your call; just don’t bust the crossing altitudes.

But when are you established on the next leg from whence you can start down? Good question, and the answer applies equally to feeder routes, transitions and even MEA changes at an en-route waypoint. By the book, you cannot cross AMASE at anything less than 4700 feet and that means that 4699 feet is a bust. But most of us aren’t that good. Neither are our autopilots. Neither is ATC radar or your 100-foot-resolution Mode C transponder.

The practical answer actually lies mostly in aircraft speed. How fast will you descend and how quickly will you initiate that descent? Consider: You’re going 120 knots. That’s two miles a minute, or a tenth of a mile every three seconds. Even if you begin a descent 0.2 miles (six seconds) before the fix, with the time it takes to actually start down and your gradually increasing descent rate, you’ll still be crossing the fix essentially on altitude. The only way you’d get in trouble starting a bit early is if you pushed over hard enough to float your approach chart (or your instructor).

No GPS?

If you’re old-school and only have the LOC/GS and DME, you note that FISTA is at 15.4 DME. Your DME will indicate 15.4 DME when you are inside 15.45 miles from the antenna. So, technically, if you start down right then you’re not past FISTA. But, as above, starting down 0.2 miles early is perfectly fine anyway. Just know that the distance displayed is rounded from what is internally calculated on either DME or GPS.

On the decreasing precision scale, the next way to identify many fixes on an approach is by crossing radials. We’re starting to split hairs here, but recall that a VOR can be up to a few degrees off and still usable for IFR flight. (Have you done a VOR check lately?)

Say the defining VOR is 30 miles away and your indicator is four degrees off. That’s a permissible error of two miles. It’s probably best to wait until your crossing-radial indicator has centered and is a needle-width or two on the other side before claiming to be established on the next leg. But even then you could be well over a mile short of the fix and quite legal. Ah, the joys of protected airspace!

Finally, there’s the VOR as a fix. This applies perhaps more to en-route flying but is still common on approaches. Remember that cone-of-silence thing? Perfect station passage directly overhead is indicated when the needle goes full scale in one direction on the way in, the To/From flag flips and the needle goes full scale on the other side on the way out.

Be careful, though. If you don’t go through the middle of that cone (as in off-center or anticipating a turn), your needle may only peg on one side, then gradually work its way back toward the center. In this case just the To/From flip may be your best indication. Geeks out there might also note that a DME will indicate altitude directly above the VOR as they cross: Cross 9000 above the VOR, and the lowest the DME will indicate is 1.5 miles, while a GPS will indicate zero, of course.

Turn Anticipation

Turn anticipation is a different matter, particularly with a GPS that’s calculating that turn to roll out exactly on the new course. Except for fly-over fixes, turn anticipation is a sign of good situational awareness and a skilled pilot.

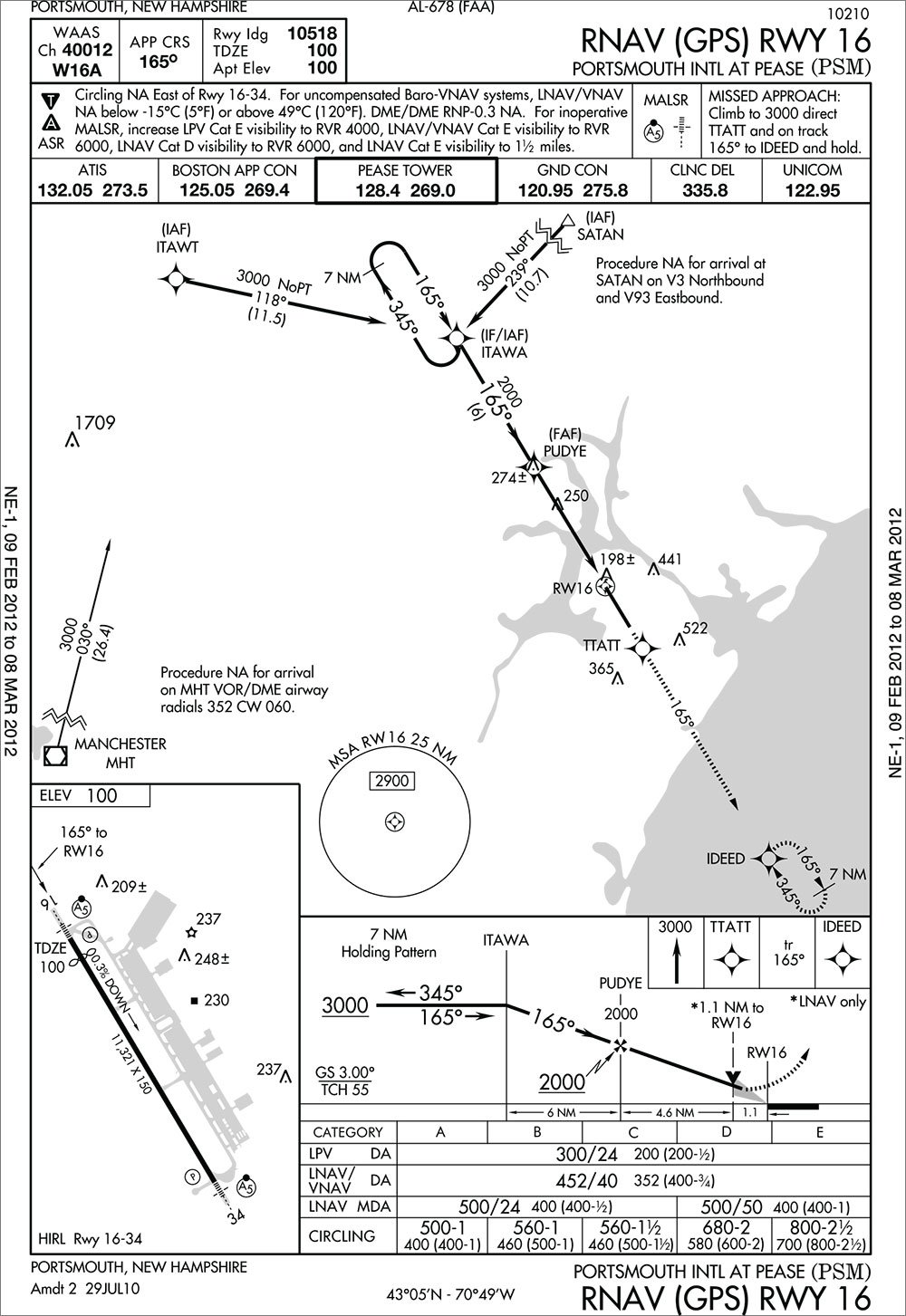

Say you’re on the SATAN transition for the RNAV (GPS) Runway 16 approach into Portsmouth, N.H., and you hear, “Cross ITAWA at or above 3000, cleared RNAV (GPS) Runway 16 Approach at Portsmouth.”

The GPS leads the turn from ITAWA toward PUDYE by over half a mile at 120 knots. As you roll into that 74-degree left turn, you start a descent to 2000, right?

Wrong. And that’s a common error. Just because you start turning before the fix—and fly-by fixes on RNAV approaches are designed expecting you’ll turn early—doesn’t mean you’re established on the next leg yet. While the error is common, it’s unlikely to hurt you. You’re in protected airspace that close to the fix, but the lower segment doesn’t really begin until after ITAWA.

Good practice is to wait until you’re abeam ITAWA to begin your descent. If you don’t have the ability to see when you’re abeam that fix (really?), think about “established” and wait until the needle decreases to about half-scale deflection for that 165-degree course to PUDYE, if your avionics work that way (see sidebar). That might be a bit conservative, but it’s certain you’ve passed ITAWA by that point. The same turn anticipation guidelines are true regardless whether you’re on approach (GPS or otherwise) or just crossing an en-route waypoint at altitude.

Does It Matter?

Unless you’re flying something with afterburners, if you start a turn or altitude change a bit early, your speed will almost certainly keep you in protected airspace, both horizontally and vertically. The hapless, sloppy pilot can be comfortable in the safe outcome within a system that is largely designed for the lowest common denominator.

But I’m going to guess that you’re not reading this to find out how sloppy you can be. You’re probably reading this to gain or retain precision—or to learn enough to make your own decisions. That’s what thinking pilots do. That, and make reasonable attempts to comply with the regulations while getting the job done. So, yes, it matters.

Half-scale? Not on a GPS turn

One of the oddities of GPS turn anticipation is that you’re never off course even when you’re, well, off course. The issue is that the route approaches the fix at one heading and immediately departs it on another heading. Unless you’re flying a helicopter, this is as impossible as it is unnecessary to do.

Traditional VOR navigation had you pass over and beyond the fix and then turn back to intercept the new course, or estimate a lead that worked so you could roll out roughly on the new course. Modern GPSs can calculate exactly the right amount of lead given your groundspeed (even factoring an anticipated change in groundspeed if it has wind and true airspeed data). But this curved path is now your course, and so long as you follow it, the GPS will show you centered on course.

That’s fine unless you want to start a descent when you’re established on the next leg and try to employ the half-scale rule. Here’s where you have to know your avionics. Some systems, like the G1000 below, will keep the CDI centered the entire time. Notice how it’s lying to a degree; as soon as the aircraft starts the turn, the HSI slews from the inbound course of 239 to the outbound course of 164. But the needle remains centered in reference to the GPS-guided turn even though you’re not nearly centered on the outbound course of 164.

This makes it tempting to start down the moment you start turning. A better plan would be to wait until the GPS sequences to make the next leg active and then start down.

Other avionics handle the situation differently. Some HSIs will show an uncentered needle from the moment you leave the inbound course until you’re established on the outbound course. The moral to the story is to know what your system does, especially if you have it coupled up with an autopilot, and when you’ll make the vertical change associated with the next leg of the approach. —JVW

Frank Bowlin is happy any time “established” doesn’t include ATC saying, “Looks like you passed through the localizer. Fly heading …”

Of course the ITAWT transition to the RNAV 16 @ KPSM starts one of the most humorous sequence of approach fixes anyone at the FAA ever came up with…

Where is the pop-up in the instrument Procedures Handbook that says ICAO definition of established is half deflection? I keep looking and can’t find it. However, on page 4-54 in the FAA-H-8083-16B, I noticed that it says:

“…For aircraft operating on unpublished routes, an altitude is assigned to maintain until the aircraft is established on a segment of a published route or IAP. (Example: “Maintain 2,000 until established on the final approach course outbound, cleared VOR/DME runway 12.”) The FAA definition of established on course requires the aircraft to be established on the route centerline. Generally, the controller assigns an altitude compatible with glideslope/ glidepath intercept prior to being cleared for the approach.”