Anything that can go wrong, will, and at the worst possible moment—so states Finagle’s corollary to Murphy’s Law. This notion is drilled into pilots from the beginning, so that it becomes second nature to have a plan to handle all sorts of potential failures that could be experienced in flight. Engine failure: check. Instrument and system malfunction: got it covered. Communication failure: no problem. GPS failure… Uhhh, what? Hang on a minute.

A reader recently told us about a GPS outage while flying VFR along airways over Arizona. The pilot reported no GPS signal for around 100 NM. Other general aviation and airline traffic in the area reported a similar loss, and ATC seemed to be taken by surprise as well.

GPS signals at the receiver are weak, so it doesn’t take much to interfere with them. For instance, in 2012, an illegal jammer installed in a GPS-tracked commercial truck to hide its location, interfered with pre-deployment testing of the ground-based augmentation system (GBAS) at Newark airport. The device was powered through the truck’s cigarette lighter.

The FAA is gradually decommissioning many navaids through a program known as the VOR Minimum Operational Network (MON). (See “The March To PBN,” March 2017). However, GPS is a single point of failure that is managed by the Department of Defense, and civil use of the system is on DoD terms. The potential for widespread GPS signal degradation or loss exists through military jamming, illegal jamming by bad guys, or even an inopportune solar flare. We need to be as prepared for these situations as for a vacuum pump failure.

They’re Jammin’

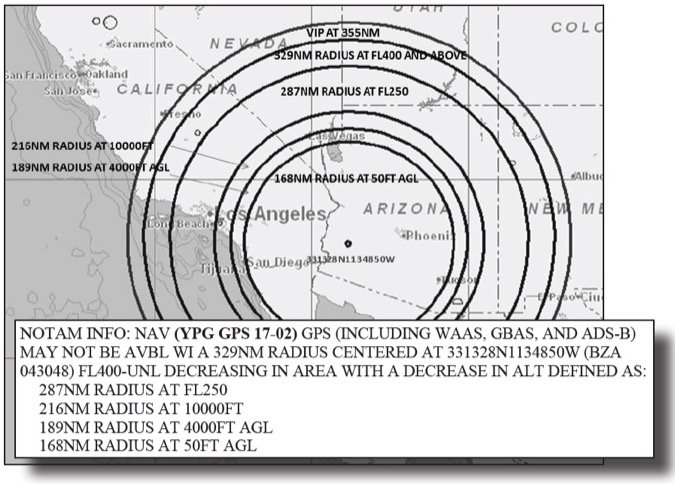

After the GPS signal loss, our reader reviewed NOTAMS and discovered that there actually was a NOTAM for potential GPS jamming being conducted at nearby Yuma Proving Ground. The NOTAM was in the en route navigational NOTAM section for Los Angeles Center and described the impacted radius and altitudes centered on a latitude and longitude location. In short, the notice was technically there, but was buried in a wall of text and not in a format that’s actually helpful for pilots or ATC.

The areas described by these NOTAMs are not graphically depicted by any of the major flight planning platforms. A graphical advisory of the event did exist but was only sent to local pilots subscribed to such notices through FAASafety.gov. Unfortunately, the pilot was just passing through and didn’t receive it. Of course it’s always entirely the pilot’s responsibility to be fully prepared for a flight, but the oversight that this pilot made is likely one that many pilots would have similarly committed.

The FAA’s NOTAM search website (https://pilotweb.nas.faa.gov) allows you to view the GPS NOTAMs on file for an ARTCC. In addition, graphical GPS flight advisories related to NOTAMs are available on the Public Notices section of FAASafety.gov (https://www.faasafety.gov/SPANS/notices_public.aspx) and are removed when no longer applicable. The graphical notices aren’t interactive or very detailed, but at least depict the general area that’s being described. The FAA also has a RAIM Service Availability Prediction Tool (SAPT) available at http://sapt.faa.gov/. It doesn’t appear fully functional as of this writing, but does provide a link to generate a KML file of planned jamming events for viewing in Google Earth.

Contingency Planning

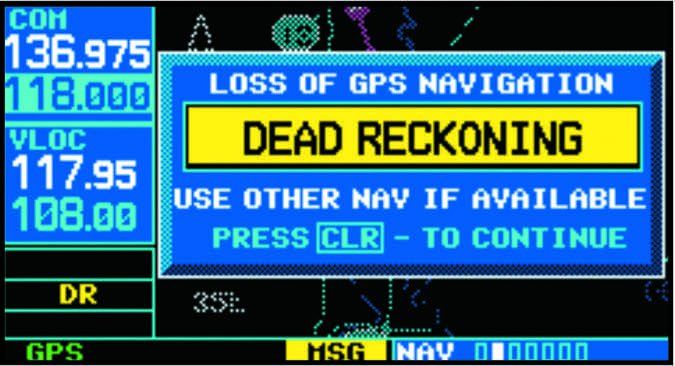

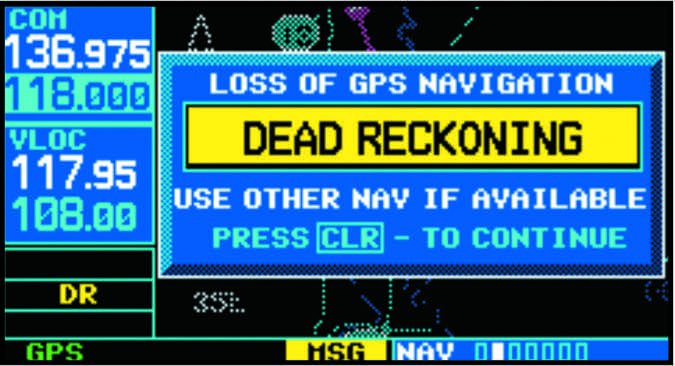

If the interference causes your GPS receiver to lose its satellite reception, IFR-certified units will give you a clear indication, but non-certified receivers like the ubiquitous tablets might not let you know. However, if the interference instead attempts to send false GPS signals (as some have reported during military jamming events), things get more interesting. The RAIM capability provided by IFR-certified GPS units should detect and exclude the faulty signals and not pass on bad position data to the pilot. Panel mounted VFR units and tablets that do not have RAIM may simply interpret the false signal, resulting in erroneous position data and unrealistic speed/altitude indications on the unit. Have fun with that.

Signal anomalies in IFR-certified GPS receivers are a required ATC report per AIM 5-3-3. After reporting the interruption, the next thing you’ll likely hear is ATC asking you to “Say intentions.” Unless you’re nearing minimums on a GPS approach, loss of GPS nav shouldn’t be an emergency, so take your time. Before reporting the loss, you should work out a plan that involves evaluating the impact of the loss of navigational capability on what you’re doing at the moment, and whether or not you’ll be able to continue to your planned destination.

That impact is highly dependent upon aircraft capability, weather, and approaches available at your destination. Many airliners and high-end business jets have RNAV systems with inertial references or DME triangulation. Those pilots might not even notice the loss of GPS right away. For high-performance aircraft capable of flight above any MVAs, ATC might be able to help with vectors. If your destination has an ILS approach, you’ll likely still be able to make it in if continued flight under IFR is required. However, many GA operations don’t satisfy these conditions, so for them there’s more to think about.

You’ve Got a Problem

If you’re on an airway at or above the MEA, just use VORs to keep going. However, if you’re below the MEA, but at or above the GNSS MEA, you might have a problem. Since the GNSS MEA doesn’t account for navaid coverage, you might not receive the needed VOR unless you climb to the MEA. If you’re unable to climb due to weather or aircraft performance, that’s a problem.

Similarly, if you’re on a GPS-direct clearance or on a T or Q route then you no longer meet the requirements for navigation, so you’ll need to work out a new clearance with ATC.

Keep in mind that as ADS-B Out becomes mandatory, it will become the primary ATC surveillance system. Since the ADS-B system depends on aircraft-reported GPS position, the loss of GPS capability may also impact ATC surveillance.

Another consideration is that many smaller airports only have GPS approaches. When that’s the case for your destination and the weather precludes getting in under VFR or on a visual approach, you’ll need to divert to an airport where you can get in visually or using terrestrial navaids. Knowing where the nearest visual conditions are is always a prudent plan, but it’s worth keeping in mind where the nearest ILS is as well when planning a flight that will rely on GPS.

During recurrent aircraft training we exercise procedures and knowledge that we need to have when it counts, but don’t typically need to use. Recurrent instrument training should be no different. Since most pilots flying with an IFR-certified GPS navigator routinely take full advantage of GPS substitution, on your next recurrent flight consider incorporating a couple truly raw-data approaches. That means no moving maps, no loaded procedures, no recommended hold entries, and no fix identification. You might find yourself needing to fall back on those skills someday, so best to keep them fresh.

One Step Forward, One Back

The FAA is fully aware that the GPS system is vulnerable to interference and that this will only become more significant as the VOR MON is implemented, so planning for GPS outages is a fundamental component of its implementation plans. A large part of the VOR MON backup plan is ensuring that there is sufficient DME coverage to allow aircraft to continue to navigate using DME/DME RNAV.

But that doesn’t help GA pilots. The FAA gives us an assurance that there will be a VOR within 77 NM that’s usable at or above 5000 feet AGL and an airport within 100 NM with a VOR, ILS, or LOC approach that doesn’t depend on DME. Ironically, achieving this might mean installing new VOR and DME facilities. Hopefully pilots won’t be too rusty to use those dueling needles again.

In the not too distant past, LORAN and VOR/DME RNAV units were the epitome of aeronautical navigation sophistication and the envy of lesser-equipped panels. These days it seems you can’t even give them away, but they might yet have some life left. An old VOR/DME RNAV unit, like a KNS-80, would allow you to still fly direct to fixes, and do a lot of what GPS allows you to do, just over a shorter range and without a pretty moving map. In addition, although the Loran-C system was decommissioned in 2010, there is renewed interest in building out an upgraded LORAN network, known as eLoran, to serve as a backup system for GPS.

Since IFR GPS receivers have become commonplace, many aircraft owners have taken to pulling ADFs and DME receivers out of their panels, presumably for use as doorstops or boat anchors. However, in a situation where GPS navigation is disrupted, this lack of capability could leave pilots worse off than when they started. Like it or not, planning for a GPS navigation outage while in IMC should be a consideration during initial and recurrent instrument training and aircraft equipment updates.

Whatcha Gonna Do?

Most of us have become so reliant on GPS that we don’t think what we’d do if it suddenly stopped working. This article made me think about that.

I’m old school enough that I have two VORs tuned when using GPS. I also flight plan with an occasional VOR on my route. However, most of my situational awareness comes from—yup—my GPS-driven moving maps. Oops.

Everything I need is in the panel, but I also use a tablet. That panel stuff won’t be much good without the GPS, but I can still easily move the maps around on the tablet. Without GPS I’ll use the charts on the tablet, just like we did in the old days with paper charts. So, while loss of GPS at cruise would certainly get my attention, it shouldn’t be too difficult to transition to VOR nav. Hopefully, you’re in a similar comfort zone for en route navigation.

But, what about approach? Sure, there’s a lot of skill overlap between a GPS and terrestrial-nav approach, so it shouldn’t matter. But, I suspect that without GPS, my stress level would rise significantly, thereby lowering my performance and my situational awareness. The answer here is probably to spend a lot more time on ground-based approaches in the sim without that moving map. —FB