Always Works for Me

In “‘No’ to Privatized ATC” (Readback, July 2018) David Chuljian’s experiences are quite different from mine. I am a GA (beginner) IFR pilot and I fly IFR and VFR with flight following in Canada and the U.S.

When I cross the border into the U.S. I don’t see any difference in communications or how ATC treats me. I filed IFR with ForeFlight and here again I don’t see any difference. I’ve never heard of a long wait for a clearance. In Canada and in the U.S. my clearance is always ready for me.

A few times, I filed VFR over the phone with Leidos and once in the air I called FSS but they didn’t have my plan. Of course, this can be challenging when a flight plan is mandatory to cross the border.

David also talks about ATC and eAPIS not playing well together, but ATC has nothing to do with eAPIS.

Andr Durocher

Gatineau, QC, Canada

Who Can Log That? When?

Mr. Bencini-Tibo’s excellent article, “Regulation Fine Points” in July might possibly leave the reader thinking that the safety pilot could log time when the flying pilot was not “under the hood.” FAA Office of Chief Counsel makes it clear in a legal interpretation on this matter dated June 22, 2009 to Jeff Gebhart, that the safety pilot can log only that time that the flying pilot is “under the hood.” Since the flight is made in an aircraft that does not require a SIC the safety pilot was not a required crew-member during the time the other pilot did not have the hood on, so the safety pilot does not get to log anything during that portion of the flight.

Also see the August 8, 2013 legal interpretation to Danny Creech that also addresses similar situations. While it refers to the Gebhart letter, it also serves to clarify the interpretations on logging with a safety pilot and also of logging cross country with a safety pilot.

Tom Inglima

Location Withheld

You are right, of course. In both examples in the article a pilot is under the hood, but we could have stressed that the safety pilot can only log the time the other pilot is actually under the hood. —LB-T

Timely Articles

I am of South African extraction, now living in Singapore, and in the fortunate position to be able to visit the U.S. two or three times a year. During these visits, I have the opportunity to do some flying, having earned my FAA Commercial ticket and Instrument Rating a couple of years ago. I file IFR 100% of the time, so your July 2018 editorial, “I Always File IFR,” resonated strongly with me. I have jokingly said to my U.S. pilot friends that I refrain from flying VFR in the U.S., because it’s too difficult. Your editorial lucidly conveyed why that is so.

I read widely in the field of flying and of all the magazines I have access to, yours is undoubtedly the one that has done the most to improve my flying. Uncannily, when I’m pondering an IFR issue or have an IFR-related question, oftentimes it’ll pop up in an IFR Magazine article in the next one or two issues I read.

Exactly that happened to me again when reading your July issue. Last week, I flew what was for me an epic trip from Houston to Indianapolis and back. There was some grim weather to deal with in both directions, and I made extensive use of my onboard Stormscope and ADS-B weather.

Against this backdrop, Tarrance Kramer’s article “When Ya Gotta Deviate,” left me slack-jawed at its timing. Most of the controllers I dealt with on my return trip were heroic. Their vigilance in keeping me away from what seemed like the worst of the weather, was profound. Even though I’d rather have read the article before my trip, reviewing Tarrance’s “Talk the Talk” sidebar in the article, I feel in retrospect that my phraseology was passable. Courtesy of the excellent article, next time I’ll be even more professional.

I still hold my ICAO Commercial license and Instrument Rating, and continue to fly in Southern Africa from time to time. In general, I don’t think that U.S. pilots realize how fortunate they are, compared to GA pilots elsewhere in the world. From being users of the best ATC system and its professional controllers, to being beneficiaries of the advocacy efforts of organizations like EAA and AOPA, in both relative and absolute terms, you don’t realize how blessed you are.

Keep up the fine work.

Name withheld by request

Thank you for your kind words and articulate letter. If at any time there’s a topic you’ve not seen in the magazine that you’d like us to cover, please let us know. Often, simply coming up with ideas for the articles is the most difficult part of the job, and reader input is critical.

Which Way to Turn?

Regarding your excellent article on localizer back courses (“Back to Back” in September), another trick to reverse sensing I learned from a CFI, “Needle Me,” as he poked me in the ribs. In other words, you are the needle; the course line is in the center.

On a font course, you are the dot and the needle is the course line. On a back course, you are the needle and the dot is the course line you are seeking. So, needle is me, needle me. I love all the mind tricks we come up with to remember things. Of course that kinda goes away with an HSI.

Bruce Bream

Cleveland, OH

Really? That Far? Always?

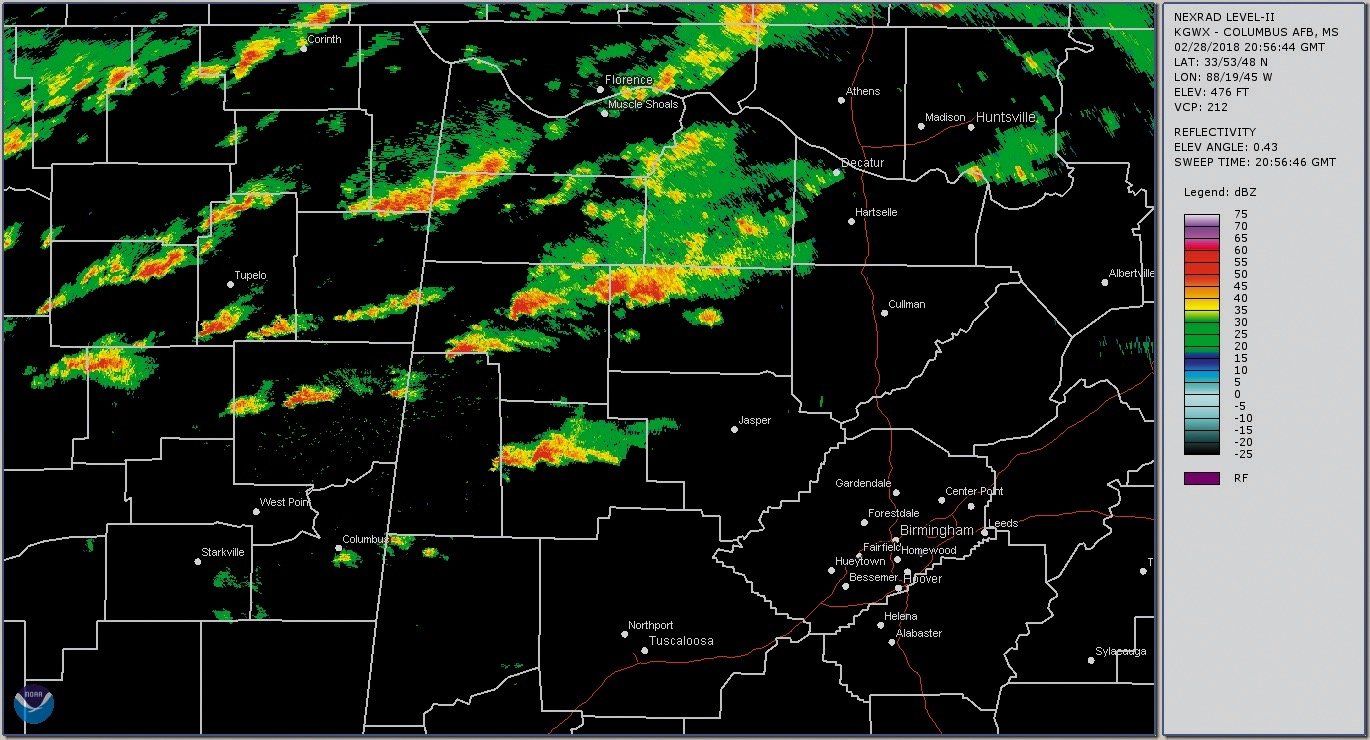

Thanks for your excellent periodic weather-accident reviews. I agree that memorable events like this do get burned into your memory. But let me pose a practical question.

Avoiding the massive storm in the Georgia example (“Weather Accidents #7” in August) seems intuitive. But what about just 1 or 2 cells on an XM download? I presume their algorithm for making this a cell means it’s bad, but do you need to avoid all cells by 20 or 25 miles?

Just last week a group of cells were lazily sliding by 10 miles from my home field, and everyone was flying around them in the sunshine and taking off and landing. They were nothing like the Georgia storm, but they were cells……

Andrew Doorey

Wilmington, DE

Like many rules of thumb in life, this one is conservative under most circumstances. And, like most, it’s not a real one-size-fits-all guide.It’s true that few “cells” are dangerous beyond a few miles, otherwise radar weather-equipped aircraft couldn’t successfully thread the needle to get through them. However, some are definite hazards out quite a ways.I remember years ago, someone I knew had just purchased a new Citation, his first jet. During his familiarization flying with a qualified instructor, they encountered some “cells” and nicely avoided them.It turned out that these particular cells were spitting out large hail stones that they could see neither visually nor on radar, and they flew right through them. The plane was significantly damaged on all of the leading edges—wings, engine inlets, etc.The final insult to that injury was that the damage came to something like high five figures and they’d opted for insurance with a deductible that was just beyond the repair costs. An expensive lesson, that.Personally, I use many indicators to tell me how dangerous a cell is. First, how steep are the gradients on radar? If it gradually goes from green to some yellow and then some red, it’s not too severe. However, if the distance between green (or nothing) and red is small, that’s a very intense cell. By the same measure, if you can see it visually, how dark, how ominous does it look? If it’s merely white and puffy, chances are it’s not spitting anything out the top or sides, especially if you can’t see anything. However, if it’s dark, with a big anvil overhead, stay far, far away. Also, passing upwind of the cell gives you more margin.If you’re unsure, just use the recommended 20 miles. Better safe with lots of room to spare, than not quite far enough away.—FB

We read ’em all and try to answer most e-mail, but it can take a month or more. Please be sure to include your full name and location. Contact us at [email protected].