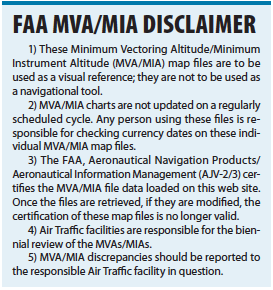

Instrument training is littered with acronyms and abbreviations. Altitudes like MEA, MCA, MOCA, OROCA can end up being the bane of students. And that’s just the en-route altitudes. When we get into the terminal environment, we then have the procedural MEAs on SIDs and STARs and, of course, the minimum—and sometime maximum—altitudes for the various segments of instrument approaches, from TAA to procedure turn to intermediate leg to FAF crossing to MDA (or DA) and finally the missed approach altitudes.

Charted IFR Altitudes

IFR altitudes published on our en-route charts, SIDs, STARs, and approach charts have a number of sources. Most are discussed in Parts 95 and 97 of the regs. Part 95 defines a number of en-route altitudes while Part 97 concerns itself mostly with instrument approaches and obstacle departure procedures. Other altitudes could be charting conventions or find their source in FAA Orders and other official nonregulatory or quasi-regulatory documents. Ultimately, though, they are all “regulatory” since the National Airspace System and its parts are all created by regulation.

However, here we are going to talk about IFR altitudes that are not charted. Other in-depth articles have covered the ones that are charted, but because there are so many and some are more familiar than others, a brief review can be helpful for context. In addition to the minimum altitudes for instrument approaches and obstacle departure procedures, we have the altitudes in the table below, which should be known to you.

Uncharted Altitudes

Minimum Vectoring Altitude

The uncharted minimum altitude most familiar to pilots is the MVA—the minimum vectoring altitude used by ATC primarily in the terminal area, although there are en-route MVAs as well. They are generally lower than the other minimum altitudes used in the terminal area—SID and STAR MEAs, TAAs, and charted segment altitudes—because the radar approach controller can “see” us and give us vectors clear of obstacles. If we have ever been vectored to the final approach course, we are familiar with the term. The Pilot/Controller Glossary contains the most detailed definition. The MVA is:

“The lowest MSL altitude at which an IFR aircraft will be vectored by a radar controller, except as otherwise authorized for radar approaches, departures, and missed approaches. The altitude meets IFR obstacle clearance criteria. It may be lower than the published MEA along an airway or J-route segment. It may be utilized for radar vectoring only upon the controller’s determination that an adequate radar return is being received from the aircraft being controlled. Charts depicting minimum vectoring altitudes are normally available only to the controllers and not to pilots.”

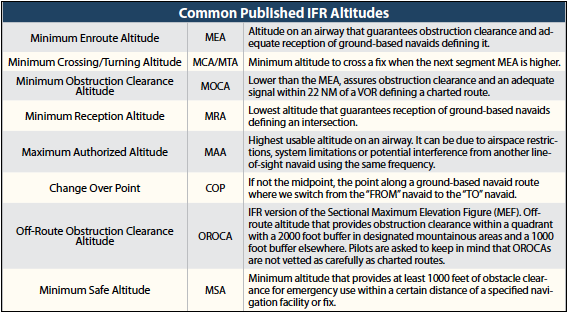

That last part—MVA charts being available to controllers and not to pilots—has generated much discussion in recent years. In reality, they are available to pilots, sort of. MVA charts are published and can be found at https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/flight_info/aeronav/digital_products/mva_mia/.

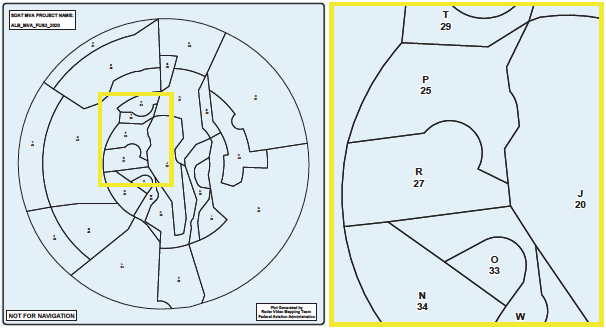

The “sort of” is that the PDFs are virtually unreadable. Look at the MVA chart from the Albany NY TRACON area above, along with a partial blowup. It’s easy enough to figure out that, for example, “R 27” on the left side of the blowup means “area R” and has a 2700 foot minimum vectoring altitude. But since we don’t know the metes and bounds of the charted area, the information is meaningless without more. For those with a bit of tech savvy, however, in addition to PDF, the FAA website provides AIXM (Aviation Information Exchange) XML files. Those can be converted into georeferenced KML (keyhole markup language) files. In turn, the KML can be massaged in Google Earth and imported as a custom layer into some EFB apps.

Some wonder why our sophisticated EFBs don’t just have them. I think the “Not for Navigation” note and the more extensive disclaimer in the PDF file give the answer. It may be fine for us to individually take the safety and liability risk associated with converting and importing them. It’s not quite as attractive an idea for an EFB developer. I won’t join the pro-and-con argument about their inflight usefulness, but only point out that they do exist and can be used at our own risk.

Some wonder why our sophisticated EFBs don’t just have them. I think the “Not for Navigation” note and the more extensive disclaimer in the PDF file give the answer. It may be fine for us to individually take the safety and liability risk associated with converting and importing them. It’s not quite as attractive an idea for an EFB developer. I won’t join the pro-and-con argument about their inflight usefulness, but only point out that they do exist and can be used at our own risk.

Minimum Instrument Altitude

Somewhat less familiar than the MVA is the MIA, the “Minimum Instrument Altitude.” It has been loosely described as Center’s MVA. MIA charts are also available from the FAA website mentioned above. Comparing them, we can see that MVA charts are generally focused on terminal airspace; the MIA charts on Center airspace. There is another significant difference. ATC use of the minimum vectoring altitude requires radar; the MIA does not. Beyond that they are similar. The layout and format are the same; the disclaimers identical, and both are intended exclusively for use by controllers, not as a navigational aid for pilots. But like the MVA charts, the MIA charts are available in both PDF and AIXM XML formats, the latter of which can similarly be manipulated into a custom map layer. Which, of course, leads to discussions about their usability.

Leaving aside the question of importing them, what are MIAs good for? We understand how the MVA makes our life easier by allowing ATC to give us more direct routing to our destination, bypass procedure turns, and give us intercepts to the final approach course. But what about the MIA? One answer is that, even if we can’t effectively use them, knowing they exist gives us options—something we can ask ATC about. Let’s try a simple scenario as an example. This is a portion of the Albuquerque ARTCC MIA chart displayed in Google Earth over a low en-route chart. We are on V83 just south of the TAS VOR at the top of the graphic en route to Santa Fe at the bottom. We are in the clouds at the 11,000 foot MEA when we begin to accumulate ice on our non-FIKI Cessna Skylane. What are our options?

A traditional analysis would tell us to climb if we can, depending on what is above us. If we know we are near the top of a cloud deck or temperatures are substantially colder where ice is less likely to form, we might give it a try. With a good preflight weather briefing and onboard weather (which can be spotty in some areas) we may have some good information for that strategy, but with a normally-aspirated engine, we might have a fairly limited climb margin. Based on the outside air temperature we think a descent will bring us to sufficiently warmer air. But the MEA does not drop to 9000 feet until reaching NAMBE intersection, almost 50 NM from where we are. So descending to warmer temperatures is not an option. Or is it?

The MIA in the area outlined in pink is 11,000 MSL, like the airway. However, although the MEA continues at 11,000 feet all the way to NAMBE, the MIA drops to 9800 feet when we cross TELOY (yellow area). That gives us the potential ability to descend 1200 feet with ATC concurrence. Simply knowing that a below-MEA option could exist gives us the incentive to key the mic and say, “Albuquerque Center, Skylane 34A. We’re beginning to pick up ice. What’s your MIA? Can we get lower?” (Those who argue in favor of including this information in our EFBs would point out that having it would enable us to use it in an emergency or lost com event.)

A technical point: Recall that the MEA guarantees an adequate VOR navigation signal. If we drop below the MEA, that signal is no longer assured. As some controllers have pointed out to me, they cannot clear us to the MIA unless we have the ability to go direct rather than on the airway defined by VORs. Although the desired track is identical, it’s the difference between flying V83 to POAKE (or some other downstream fix) and flying “Direct POAKE” using GPS. One would hope for a controller who will respond with “Can you accept Direct POAKE?” but be prepared to request it.

Eye of the Beholder

As mentioned, a hot topic in aviation discussions is the creation of pilot-usable MVA and the lesser known ATC MIA charts. Given the FAA warnings about currency and accuracy, I don’t expect them to be available any time soon. Their usefulness as an overlay is a matter of opinion.

Some say knowing the MVA or MIA would be a help in flight planning, emergencies or lost com. For them there is the option to create EFB custom layers and use them at their own risk. Others question the practical value. But this answers questions about how ATC can vector us for an approach below published altitudes. Knowing controllers have MVA and MIA charts that might permit them to clear us to a lower altitude if asked (in the right way, of course) lets us know we have options which may not be reflected on our charts.

In case anyone’s interested, the tracon and *some* of the artcc mva/mia maps in a format importable into google earth and foreflight are now available here: https://github.com/dark/faa-mva-kml.