Many of us are in need of some instrument refreshing. After the usual winter hiatus, followed by all the restrictions of COVID-19, themrust might be thicker than usual. So once you’ve gotten reacquainted with your local ILS and LPV approaches, practice some edge cases, like a nonprecision, non-GPS approach.

One favorite is the circle-to-land. If you’re lucky enough to have an airport nearby with a VOR-A (seriously), that’s perfect for our purposes.

Ah, yes. The VOR-A wasn’t so much a procedure as it was an exercise or, (ahem) an “instrument” of torture, used by your CFII to check off some boxes: Ground-based non-precision approaches, circling approaches, and landing from a circling approach (all required training). Haven’t done one since the checkride? Oh, you’re in for some fun.

Trimming Minimums

Our choice for today’s abuse is Henderson, Kentucky. KEHR does have RNAV approaches to 9 and 27, but you’re not allowed to use them today. Besides, they don’t have circling minimums. While some GPS-A approaches exist for obstacle criteria and such, they’re scarce. As the satellite-dependent airspace system progresses, the FAA has been phasing out circling approaches as airports with few navaids—like Henderson—get RNAV approaches to each runway.

To that end, the FAA published a new policy on cancelling instrument procedures, with much attention paid to circling minimums and circling-only approaches. That makes Henderson’s VOR-A at risk for cancellation. The FAA said, “As of March 29, 2018, there are 12,068 IAPs in publication, consisting of 33,825 lines of minima, 11,701 of which are circling lines of minima … Circling procedures account for approximately one-third of all lines of minima for IAPs in the NAS.”

At risk or not, there are still plenty of circling procedures. In general, they can be created for one of three reasons. At Henderson, the final course is more than 30 degrees to either runway, which is the most common reason to designate a circling approach. The second would be a descent gradient “greater than 400 feet/NM from the FAF to the threshold crossing height.” Third reason, strange as it is: “A runway is not clearly defined on the airfield.”

Yup, Non-Precision

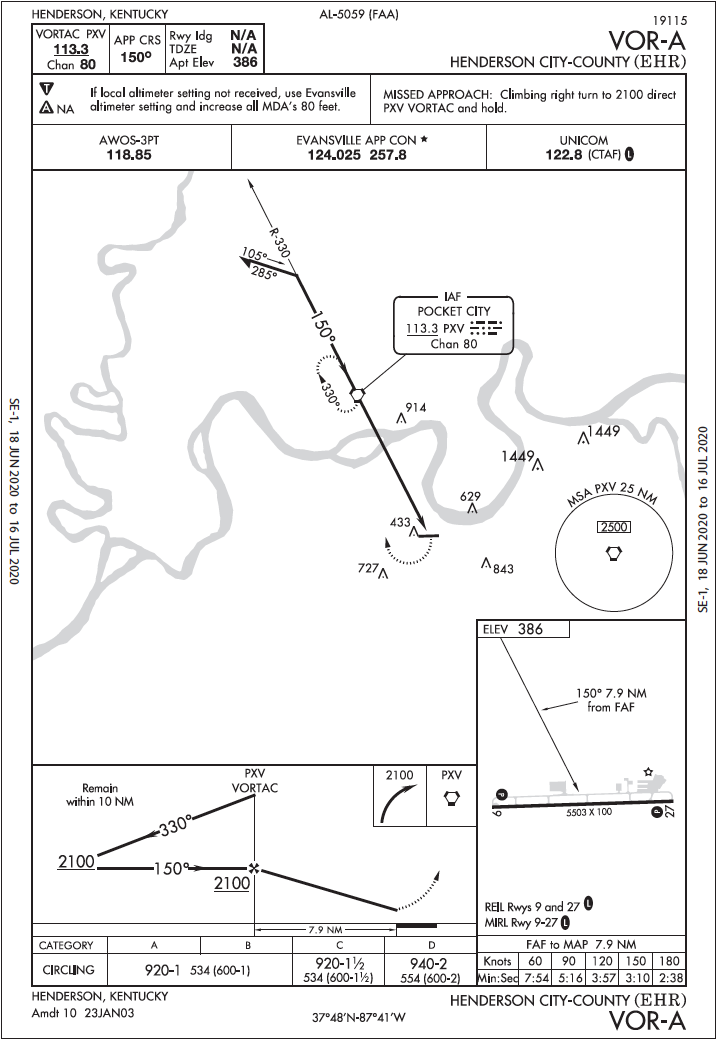

The VOR-A at Henderson is typical for this kind of approach. The IAF is the Pocket City VORTAC eight miles northwest of the airport; it’s also the final approach fix and the holding fix. Doing the course reversal? File to PXV and get cleared for the full approach. Getting vectors from Evansville Approach? Again, file to PXV. It’s the perfect parking spot in case of a comm failure, ATC delay, weather delay or aircraft issue, or a combination thereof. (We’ve all had those days.)

Henderson’s weather today is 900-2 with west winds at 10 knots. The circling MDA of 920 feet provides a seemingly tight 534 feet between you and the ground. This is a typical minimum for a circling approach—round this one to 600 feet and there’s the ceiling required to make it work. Still feels tight? You’re not alone. Most airline and charter operating rules require weather to be at least 1000-3 for circling. While this is mainly due to the wider circling space required for larger, faster aircraft, those numbers are perfect for anyone’s personal minimums in any aircraft.

Next, the inbound course of 150 degrees goes to the middle of 9/27, about 120 degrees offset from Runway 27. We’re talking non-precision for real. There’s no DME, no on-field navaid, so it’s a timed approach from the FAF that requires guesstimating.

You normally fly final at 100 knots with a notch of flaps. That’ll work here, but remember that the chart’s timetable is based on groundspeed: 5:16 at 90 knots, 3:57 for 120 knots. With a slight tailwind inbound, figure on coming inbound a bit over 100 knots, so settle on the halfway mark—4:35.

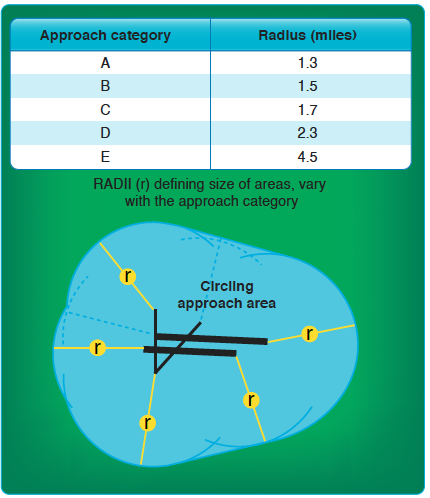

Now pick the approach category. You’re an A or possibly B, and the MDA’s the same for both. Approach categories, as defined in the IPH, are derived from carefully defined speed criteria bookended by rather wide speed ranges to determine the category. Think this is pretty open-ended? Keep reading.

The category (and speed) at the time of flying an approach is (somewhat) up to the PIC. Specifically, plan on 1.3 VSO (again, a guesstimate as this is based on max weight). For 80 KIAS, it’s Category A with a radius of 1.3 NM. If you prefer to use 90 knots and end up flying close to the B category, fine, just adjust MDA if necessary. Anyway, this is about planning ahead, so consider rounding up to 1.5 NM for some margin.

Note the 433-foot MSL obstacle at the departure end of 27. Check the takeoff obstacle notes and you see it’s a pole north of the centerline. Plus, there are objects, some more than 100 feet high, at both ends. As a reminder in the IPH: “A minimum of 300 feet of obstacle clearance is provided in the circling segment. Pilots should remain at or above the circling altitude until the aircraft is continuously in a position from which a descent to a landing on the intended runway can be made at a normal rate of descent and using normal maneuvers.”

“Normal” is a bit subjective, so it’s best to fly common-sense turns, descents, and speeds. To get set up comfortably, fly a smooth but timely descent to 920 feet soon after PXV, overfly the runway, and enter the left downwind from there. This not only makes the FAA happy, it complies with the standard traffic pattern. It also lets you scope out the runway before landing.

If You Miss

The depicted missed approach is a climbing right turn to PXV and hold at 2100 feet. Where must you start the missed? If the time’s up and there’s not enough of the runway environment, lighting, etc. to legally continue, it’s missed approach. Circling guidance emphasizes the need to fly at MDA, above obstacles and below the clouds, until established on final to the runway. If not, but still visual, do another circuit ‘round the pattern and back to downwind. If you’re using a higher MDA for yourself, assume you’ll have time to make a comfortable miss/ continue decision on that 150-degree course just north of the runway. Continuing? Fly into the left downwind for 27. Miss? Follow the procedure.

Now for a bigger caveat: what if you’re on the left downwind and get into IMC, or fly too far south and lose sight of the runway upon making the turn to downwind? Here’s where a good approach briefing can save you. Consider making a climbing left turn—essentially in the pattern—to get back over the runway, which is the safest place to be if not on the actual missed approach path. Roll out at 270 degrees up the runway (using normal maneuvers for IMC) until you reach the initial safe altitude (920 feet) for the missed. Passing the 150-degree radial from PXV, you can then point yourself toward the VOR and continue to tweak the needle from there. And if there’s any kind of GPS on board, feel free to use it legally as an “aid to situational awareness.” It’ll help confirm position while on the timed approach, and keep you oriented if you miss in an awkward spot. Plug in PXV and KEHR, or the approach if it’s available.

All these details are why everyone, the FAA included, calls the circling approach among the most difficult IFR procedures, with a corresponding increase in risk. Add the VOR aspect and it’s also among the most imprecise of operations. That means making one judgement call after another, so making those calls ahead of time is the best way to show off your newly discovered, or rediscovered, circle-to-land skills.