The national news seldom trains its eye on the FAA. So it was unusual when FAA Administrator Michael Huerta made the news with a speech he gave to the Flight Safety Foundation last October. His speech centered on a newly effective “Compliance Philosophy” which could represent a sea change for better relations between pilots and the FAA.

Among the many things he said was that the aviation environment has reached a level of complexity where just applying rules no longer improves safety, because improving safety is an endless evolution. Put another way, static rules do not suffice in a dynamic environment.

Example: Airline passengers in the U.S. take safety for granted. Fatal accidents in commercial aviation were one per 3.1 million flights in 2015. This did not just happen. It resulted from the FAA and the airlines working together to “identify hazards, assess the risks from those hazards, and put measures in place to mitigate those risks.” This ongoing effort has paid off handsomely and might work for general aviation.

The Compliance Philosophy

Having worked so well for the airlines, the FAA expanded the concept of working together to improve safety into something called the Compliance Philosophy. Its focus is simple: Find problems in the National Airspace System (NAS) before they cause an incident or accident. Use the right tools to fix them. Monitor afterward to make sure the fix remains.

Refreshingly, and implicit in its title, the Compliance Philosophy acknowledges the reality that most of us voluntarily comply with the rules. The inevitable bad eggs cause the FAA to shift to enforcement. While no one gets a free pass, enforcement results only if offenders resist compliance. Yes, resistance is futile.

Compliance Philosophy recognizes that even the best operators make honest mistakes. But, that is no free pass. When this happens, the first effort is to use training or documented improvements to bring the matter into compliance. This positive and productive approach has made U.S. airlines the safest transportation mode in history. Now it’s GA’s turn.

That said, many GA pilots deeply distrust the FAA, an attitude which in my view the FAA brought upon itself. Over the years, the once-cordial relationship between pilots and the FAA deteriorated into an FAA-versus-us mentality. This unfortunate course of events is due to the belief that the FAA’s preference is for the stick of enforcement rather than the carrot of compliance. Senator Dan Inouye’s Pilot’s Bill of Rights exists for that reason.

Administrator Huerta acknowledges this issue, saying that, “the Compliance Philosophy requires both the FAA and the aviation community to evolve in how we do business and how we interact with one another.” Given what we stand to gain in safety terms, I heartily agree with that statement.

Even so, trust, once broken, is hard to rebuild. The FAA’s tradition of—sometimes mindlessly relentless—enforcement needs to change. We are asked to make some operational changes, too, which are sensible and not at all onerous. More on that shortly.

Implementation

According to Administrator Huerta, all FAA employees are being trained to apply the Compliance Philosophy, not just in the abstract, but in “How do I implement it in the work I do?” For instance, instead of using arbitrary dates to conduct inspections, inspection intervals are now being adjusted based on applicable data.

Perhaps most important, the FAA stresses that employees apply critical thinking. For example, inspectors are now required to use their skills to identify risks and then use appropriate tools to permanently fix the problems.

What is asked of us as GA pilots? Administrator Huerta does not address this specifically, but he says that compliance “means going above and beyond,” such as developing and implementing risk controls appropriate to our individual operational environments. This would include setting personal minimums, applying IMSAFE, PAVE and other guidelines. He asks us to think about outcomes and performance, hazard identification and mitigating those hazards before flight. It’s all about accountability which looks forward, versus blame which focuses on punishment after the fact.

Compliance, he says, is the most important factor in safety. Rapid return to compliance, mitigating risk and ensuring positive, permanent change all benefit the aviation community. That, he says, is what the Compliance Philosophy is all about.

New Priorities

John Duncan heads the Flight Standards Service. In his view as well most people want to be compliant. Pilots don’t set out to break rules. Failures to comply are almost always unintentional, and can be the result of lack of training or knowledge, inadequate skills or procedures that don’t work right.

Echoing his boss’ sentiments, the correct response to unintended errors is accountability, which means taking responsibility and looking forward, not fixing blame.

Mr. Duncan believes that the greatest safety risk in the NAS is not a specific event or outcome. He believes it necessary to look at the operator’s or pilot’s willingness and ability to comply with safety standards. The biggest risk is the operator or pilot being unwilling or unable to comply with the rules.

An unwilling pilot is one who knowingly breaks rules or takes inappropriate risks. The term also covers an uncooperative pilot who won’t help fix the problem. Conversely, a pilot who makes a mistake and reports it through the Aviation Safety Reporting System is regarded as having a “constructive attitude,” which can make the difference between being penalized or not, and if penalized, determining whether the penalty is large or small.

An unable pilot is one “who fundamentally lacks the skills or qualifications needed to comply with the rules.” As aviation sins go, this might be the worst. Who would want to share the air with such a pilot?

At sum, if you are willing and able to comply, and you cooperate in getting back into compliance, such as attending remedial training, then you stand the best chance of avoiding an enforcement action. The FAA reserves enforcement for the unwilling or unable. Enforcement’s purpose is to rehabilitate and bring the guilty party (pilots, operators, mechanics, etc.) back into compliance such that they become willing and able to meet standards. For those beyond redemption, stronger enforcement means kicking that person out of the NAS, as in a certificate revocation.

The Compliance Philosophy is not new; many inspectors have applied its principles for years. Many, but not all. You could get the mild-mannered Inspector Jekyll or the evil Inspector Hyde. Either way, your flying fate rests in their hands. Within Flight Standards, the new philosophy officially clarifies FAA priorities: rapid compliance; elimination of safety risks and ensuring positive and permanent change. The Inspector Hydes within Flight Standards will need to change.

One thing that will be expected of us will be self-disclosure of errors, particularly through ASRS, which takes on added importance, especially since it carries the prospect of immunity. This essential part of the Compliance Philosophy makes it possible to find and fix problems before paint gets scraped. The word “compliance” means operating not just within the letter of the law, but within its spirit, too. Most of us are proud to do that.

Compliance

We all know something about Risk Management. It is embodied in the IMSAFE and PAVE checklists. A key, but less-known, element of Risk Management is an offshoot called Risk-Based Decision-Making (Yes, another acronym: RBDM). It falls squarely under the Compliance Philosophy because it is completely proactive. Unlike in-flight aeronautical decision making, RBDM is applied before flight. Part of its essence is memorialized in 91.103, Preflight Action. RBDM asks us to consider every known factor with the purpose of identifying and mitigating any hazard potentials.

The first question is whether to fly or not. The weather might be below your personal minimums, or the aircraft might not be up to the job. Our flight school forbids flight when the winds are 30 knots or greater. We recently canceled a flight because both prospective destinations were forecasting 30-knot winds, and we didn’t see any fun in getting kicked around like leaves in the wind.

Both the PAVE and IMSAFE checklists fall inside RBDM. If you are eager and looking forward to the flight, fine. If hesitant or uncertain, that says something, too.

Recently our flight school decided to send a young instructor from Florida to Colorado to pick up a Cessna 172 and fly it back. When I heard of this, all kinds of red flags went up. A flat-lander like myself, the pilot would be departing a 5200-foot field-elevation airport on the Front Range and flying east into lower elevations. I suggested he ask around the airport for any tips. He knew to lean for best power on departure. I gave him an Instrument Proficiency Check, but as is commonly misunderstood, an IPC is no quick-fix or assurance of real instrument proficiency.

We discussed the airplane; well, we tried to. He knew nothing about it. Was it a VFR-only airplane? Did it have a G1000 or a GPS? If it did, did he know how to use it and was the database current? Was its registration current? Altimeter/transponder check? ELT? How about proof of an annual inspection? AD compliance? He had no idea. He contacted the owner and eliminated a whole bunch of risk in one phone call.

I didn’t realize it then, but we were practicing RBDM, putting ourselves in an unfamiliar place and trying to learn everything possible in order to mitigate as much risk as possible in advance. In doing so, he won a mental victory before ever setting foot in the airplane. The flight went well.

In another RBDM instance, my student planned an IFR cross-country, which if flown directly, would have taken us over a large body of water and beyond gliding distance of land. After we talked about that, he chose to fly a slightly longer route but with much less over-water exposure.

Above and Beyond

Data collection is an essential component of the Compliance Philosophy, but ASRS reports alone are insufficient in volume and detail. Large amounts of detailed data are the only way to identify trends, subtle problems and especially problems in the making. From this realization emerges a new concept: Flight Data Monitoring. No, it’s not Big Brother in aviation. Read on.

(Warning: Acronym storm ahead.) To accomplish the striking safety improvement in the airlines, government and industry established a database called the Aviation Safety Information Analysis and Sharing (ASIAS) program. ASIAS collects “big data” from the airlines, which allows a consensus-based approach to improving airline safety based on enormous volumes of data.

In 2011, the National General Aviation Flight Information Database, or NGAFID was created to serve GA. Its role is to “collect, archive, analyze and disseminate de-identified flight data to participants and aviation researchers” according to the FAA. The key word here is de-identified. This is not some sneaky way to monitor where or how you fly; it only collects generic flight data for safety research. The database is operated and maintained by the University of North Dakota. Their role includes making sure that collected flight data is accurate and protects the privacy and security of voluntary contributors. NGAFID and ASRS reports are identical with respect to anonymity and immunity from FAA enforcement.

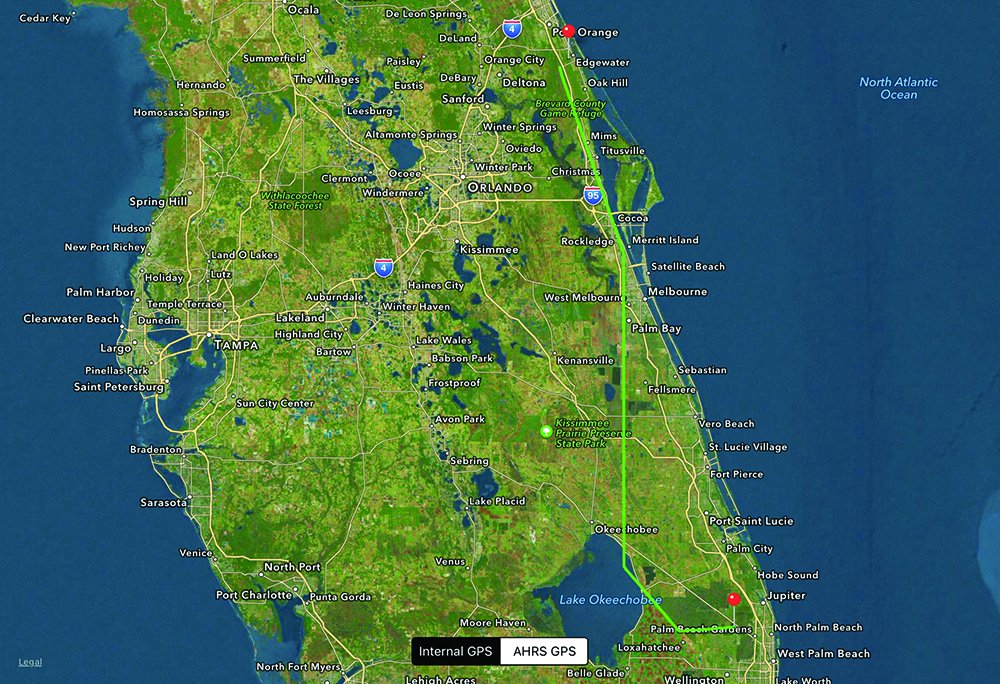

To collect the data, MIT Research and Engineering (MITRE) built an app called GAARD (General Aviation Airborne Recording Device), compatible with both Android and iOS operating systems. GAARD lets users upload de-identified flight data consisting of 86 parameters to the NGAFID. More directly, GAARD permits us to visually review recorded flight-track data, and hopefully improve our flying. Uploaded data can even influence FAA airspace design and aircraft routing. Visit NGAFID.ORG for more info on GAARD.

The volume of data must grow large enough that effective safety mitigation becomes possible in the GA community. To do that, we must participate and help build the database. The QR code on the left will take you to www.ngafid.org for information about the app and links for download. If we all kick in, we can hopefully achieve airline-level safety.

Fred Simonds just downloaded the GAARD application and can’t wait to use it in Florida. See his web page at www.fredonflying.com.