Good single-pilot resource management calls for three basic elements: Knowledge of one’s aircraft systems and characteristics, proficiency in their use under various conditions, and well-crafted, consistent routines. Those well-crafted, consistent routines—standard operating procedures, SOPs—encompass flows, checklists and callouts, but go well beyond the basics.

We’ve started down the path toward personal SOPs in “Using an SOP in GA” in the September 2016 issue. In October we introduced the idea of scrapping the manufacturers’ “do lists” in favor of building a flow and checklist of your own that we detailed last month. This article is the first of two that will help you bring these concepts together into your own SOP.

The NTSB has repeatedly shown that in accidents involving professional crews, “non-compliance” and “non-existence” of SOPs is a common factor. If SOPs are good for the pros, perhaps we should use them, too.

We can adapt guidance for the pros to our single-pilot flights. FAA Advisory Circular 120-71A is a good starting point along with your custom checklists, the aircraft POH, and your own best practices. This will not only give you that go-to reference for every phase of flight, but you’ll also be getting a thorough review of your own CRM—hopefully with improvements.

Cockpit Culture

Your SOP reflects the particulars of your flying. We’ll assume you’re single-pilot in an aircraft you know well. Are you in a six-seat, six-pack single-engine bird with a two-axis autopilot? …an older light twin with a new panel? Do you normally fly the same long legs, or shorter trips to unfamiliar airports? This big-picture stuff will help you decide the content of each section, each procedure in your SOP.

Be sure to include a sterile cockpit policy. Just as commercial flights must keep sterile cockpits below 10,000 feet, you’ll have a similar routine. An SOP as basic as “maintain sterile cockpit below 4000 feet above the field on departure and arrival” should allow you to complete climb and descent chores.

Automation Philosophy

Another baseline to consider is how you manage automation. Consider limits for its use, such as not engaging anything below 700 feet AGL and disconnecting on approach no later than leaving minimums to land, etc.

Regardless of your aircraft’s capabilities, situational awareness is crucial. Per AC 120-71A, the Pilot Flying will “monitor/control the aircraft, regardless of the level of automation employed.”

To be even savvier with your equipment, figure out when you’ll want to step up or step down in levels of automation. For example, when given a shortcut on your assigned route, you needn’t turn off any autopilot functions; just hit direct and navigate to the fix. But when told to maintain your current heading past a fix on the route, you’ll likely step down into heading mode to stay with ATC instructions.

The AC discusses this while noting that you should always cross-check the flight plan with your clearance any time there’s a change.

Getting Personal

For those who self-brief, self-dispatch and such, a simple six-item section can cover the main elements of pre-flight considerations:

1) Create and study the flight plan.

2) Obtain flight briefing: standard, then abbreviated as needed.

3) Review departure/arrival conditions for a go/no-go decision based on personal minimums.

4) Alter flight plan as needed.

5) Note required equipment.

6) Complete performance and weight and balance calculations.

Include policies for alternates. (e.g. “Always file at least one alternate, regardless of weather.”) Add departure minimums like, “Departure ceilings and visibility must be at or above circling minimums for an available approach.”

Personal minimums should also include maximum crosswinds and wind velocity, runway lengths, and whether you’ll depart with any questionable weather en route, such as convective activity or reported icing. For some pilots, these items can be variable depending on recent flight time, time in type, etc. This illustrates the need to review and update your SOP over time as your capabilities develop.

When using an electronic flight bag, the flight plan and briefing will go hand-in-hand. Just make it a standard procedure (part of Item 1) to examine the segments of your route on a chart after entering it into your EFB. Look for standalone stuff that won’t always appear on a standard briefing, such as special use airspace, unusable VORs or airways and, of course, terrain (including open water) and obstacles on departure and approach.

Must-Dos Before Going

Passenger briefings are a must for every flight, so include them in your pre-start checklist. If you have additional special items like portable oxygen, flotation devices and other emergency equipment, include those in your SOP for reference.

A takeoff briefing should be required every time and can be almost a predetermined script covering aborted takeoffs, emergency procedures after takeoff, climb speeds and configuration and when to engage the autopilot.

Consider discrepancies you discover. Naturally, anything that renders the aircraft unairworthy or inadequately equipped is an automatic no-go. Your SOP should consider a personal MEL to make other decisions for departing IFR or VFR, day or night. Some like having a blanket policy that any problem with IFR-equipment will cancel any cross-country flight, even if in VMC, or failure of the autopilot could mandate no IMC.

Get It Stable

SOPs should specify when to have the weather in hand, complete approach briefings and set up navigators and radios for the approach. This point can be determined using time, distance, or altitude from the destination. High flyers usually have all these things done before descending through FL180. Those flying lower might want them done before initial descent. Another common point in single-engine ops with GPS is to use 20 minutes out to start preparing.

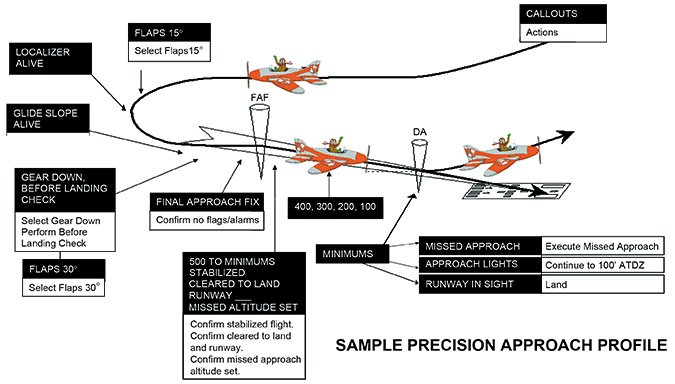

Upon receiving the first vector, you’ll activate the approach on the GPS and again review the final descent with missed approach, heading, altitudes before and after the final fix, timing and DA or MDA.

Just as in commercial operations, stabilized approaches should be a prerequisite to landing, even in VMC. As defined in AC 120-71A, SOPs call for a “constant-angle, constant-rate of descent approach profile ending near the touchdown point, where the landing maneuver begins” and “should be stabilized by 1000′ HAT in IMC, and by 500′ HAT in VMC.” (“HAT” is height above touchdown or touchdown zone elevation.)

Be sure your landing checklists are completed by the same point every time, whether it’s at an altitude (1000 feet above minimums, for example) or location such as by the FAF. For single-pilot cockpits, earlier is better as there’s no one else to help monitor the aircraft once starting the final descent and watching for the runway environment.

When It Goes Wrong

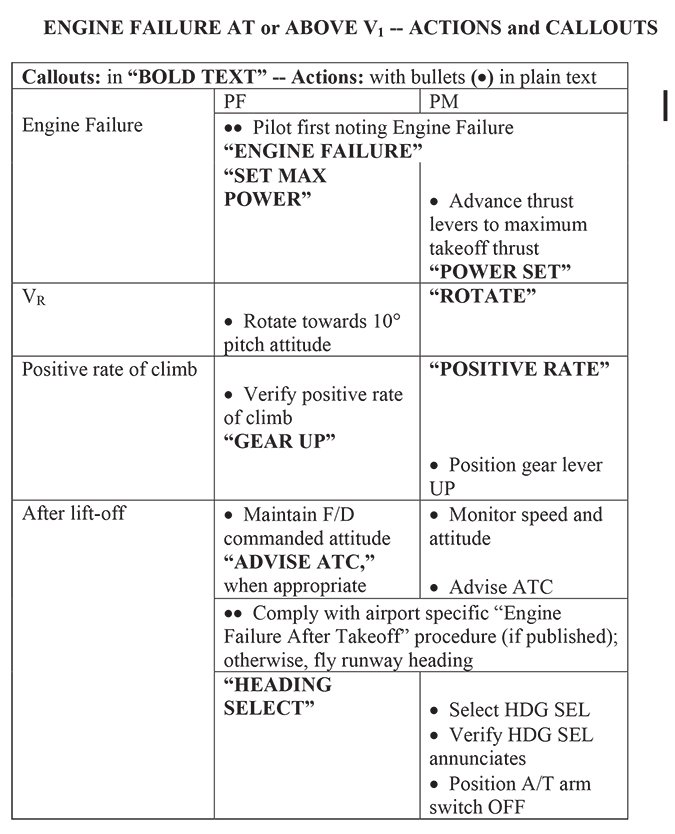

A section on abnormal and emergency items will spell out what should be done with checklists (abnormals) and which should be memorized flows and callouts (emergencies like engine failure and engine fire) followed by a checklist. Many mechanical issues, such as an alternator going offline or uncooperative landing gear, will usually fall into the troubleshooting category and probably have checklists or procedures in the POH.

While creating your SOP, you’ll discover if you can indeed perform memorized cockpit flows and callouts for each emergency. If not, it’s time to relearn the emergency procedures and configurations (including speeds), and work through the flows for each scenario.

Don’t forget the handful of abnormal and emergency items that might not have written guidance via checklists, the POH, or flight manual supplements. These include terrain warnings, icing escape, flight control failures and windshear escape maneuvers. If you don’t have specific guidance for any item, develop an SOP using outside resources such as training guides, type clubs, and knowledgeable instructors.

Your Standard Operating Procedures should be a personalized guide for good CRM, documenting how you’ll fly with consistency, discipline and professionalism—all of which should keep that safety margin as wide as it can be.

Next up: We’ll build on this and previous articles to create a sample SOP and provide the final guidance you need to make your own.

Elaine Kauh is a CFII in eastern Wisconsin. She enjoys her duties as pilot monitoring, mainly because she gets dibs on the mic.