Photo by Flight Deck Images

Question: What do pilots hate most of all? Answer: Check rides

Question: Other than check rides, what do pilots hate most of all? Answer: FAA ramp checks

Question: OK, other than check rides and ramp checks, what do pilots hate most of all? Answer: Thunders…

Enough. What pilots hate, almost more than anything else are surprises. This might not be obvious, but think about it. If you know what’s coming, you’re prepared for it, but the unexpected requires a deviation from a carefully laid out plan and an increased opportunity for mistakes—or worse.

One more question: How are professional flight crews—airline, charter or corporate—like football teams and a Shakespearian actor? Briefings.

Shakespeare and Football

Football? Briefing? Why do the teams go into a huddle? They do that so that the team will know what is going to happen and they’ll be prepared to do their part for a successful outcome.

Shakespearian actor? Old Bill Shakespeare had a little trick called an “aside” that he used when he wanted an actor to brief the audience on what was going to happen by seemingly thinking out loud. Bill knew when to use a surprise and when not to.

Similarly, professional flight crews conduct various taxi, takeoff, departure, arrival and approach briefings.

At least they are supposed to. A review of accident statistics will show that in many airline, charter, and corporate aircraft crashes, a missing or inadequate briefing was at the root of the problem.

Why are briefings so important? Well, as we discussed, briefings help us avoid surprises. However it goes beyond that. Briefings act to reinforce the use of standard operating procedures (SOP) and help reinforce memory.

Think about this. When you go to the grocery store with a list you’ve written of the things you need, you often don’t even refer to it when shopping. Instead, you use it only as a checklist to make sure you got everything. You remember the items because you wrote them down.

That is what briefings do. Because you say the items on the briefing out loud—important; we’ll get to that shortly—it reinforces the items in your memory and that of your other pilot (if any) or even passenger.

Talk to Yourself

“All well and good for aircraft with two pilots,” you say. “But I fly a Cloudsmasher 300 single-engine passenger aircraft. I am alone. I don’t have a copilot and usually not even a passenger. Who do I brief?”

No matter. You brief yourself. A briefing will work for you just as well as for the pilots in the heavy iron and the corporate jet.

So, how do you conduct a briefing, when you are the only one in the airplane? Simple. You pretend that you are not alone. You give the briefing out loud just as if you had a copilot. If you have a passenger, you can give the briefing to that person or persons. It doesn’t matter that they might not understand what you are saying. The fact that you are saying it out loud plants it in your mind.

So, how would that work? After you get your IFR clearance, before you taxi out, pull off to the side of the ramp or someplace out of the way, and say, out loud, “I am going to depart from Runway two-seven. At five hundred feet, I will turn right to a heading of three six zero and intercept the three-three-zero radial of the Podunk VOR and track it outbound. I’ll climb to my cleared altitude of five-thousand feet, which I have set in the altitude preselect. I have the heading bug set on the runway heading of two-seven-three which I’ll confirm on the initial takeoff roll to make sure I got to the right runway. I have the Podunk VOR tuned in nav one and the three-three-zero radial set in the HSI. I have the tower frequency of one-two-six point four set in comm one and the departure control frequency set in comm two. The transponder is set to two-seven-four-zero and is on now.

If you just read that out loud, I think you can see how it will stick in your mind.

Have a pen and paper available at all times when you fly IFR. Write down all frequencies. I have found that the enroute chart is a good place to do that. And if you write it down in the spot where you got the frequency change, it will be there the next time you need it.

Don’t use paper charts? Then carry a supply of note pads and write the frequencies on that. Write down altitudes, too. If you have an altitude preselect or reminder, use it.

You should always read back all altitudes, headings, altimeter settings and frequencies. Say them out loud even if it wasn’t an assignment from ATC you have to acknowledge. Again, because you read it back it helps you remember it and you can often hear an error you might make. Plus if you are on the radio, it gets it on the ATC recording that you read it back. That may help if there’s ever a question about that at your hearing.

What hearing? The one at which you’ll be the guest of honor if you screw up and are charged with a deviation.

Cruizin’ Along

While you are enroute, kicking back and looking forward to the BBQ lunch you’re planning at the other end of the flight, as you get close and are able to determine the runway and approach you will use for the arrival, it’s time to plan the arrival.

Your briefing for the arrival and approach follows the same format as the takeoff and departure—same song, second verse. After you are cleared for the arrival and load it in your navigator, then say—again out loud—what you’re going to do.

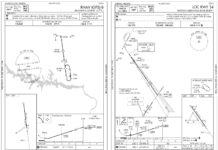

“I will cross the DUFUS intersection at five thousand feet, then descend to three thousand feet going direct to the ILS initial approach fix of SUFUD. Prior to SUFUD I will tune the ILS frequency of one-zero eight-point one on nav one and identify ISPG. The inbound front course is one forty-eight. After SUFUD, I will fly the ILS. I’ll be fully configured by the final approach fix of FUDUS, which I’ll cross at seventeen hundred twelve feet on glideslope. I’ll continue the descent to the decision altitude of eight hundred and sixty feet which is two hundred feet above the runway. My ‘to go’ calls will start at thirteen hundred sixty feet with five hundred to go. The field elevation is six hundred and sixty feet. If the runway environment is not in sight when I reach eight hundred and sixty feet, I will miss the approach. The missed approach procedure will be to climb on the runway heading of one hundred and forty eight degrees and climb to an altitude of three thousand feet, and turn left, going direct to the Cedar River VOR, one oh eight point nine, which is tuned and identified in nav 2. The holding pattern at the Cedar River VOR will require a teardrop entry. There is terrain to the west.”

That’s a rather complete approach briefing and it takes about one minute to say.

Be sure to review the airport diagram. Work out a plan for how you will taxi to your parking. Brief yourself (out loud) on the runway turnoff and taxi route. Plan your exit from the runway and the one you’ll take if you miss the one you plan.

“I should be able to comfortably make the Alpha Three exit to the left. Missing that, I’ll use Alpha Two. Off the runway, I’ll turn left on Alpha and taxi to the ramp using Alpha One. Transient tie-down is in front of the terminal, by the fuel pumps.”

You will be surprised at how much this will help after you land. It removes all the stress when the tower gives you the taxi clearance that you’d been expecting since cruise.

Don’t Rush—Be Prepared

If ATC issues you a clearance for an approach you hadn’t planned, tell them that you’ll need delaying vectors or a hold. Do not let ATC or anyone else push you into being in a hurry. Because if you get in a hurry, you will make a mistake.

So, take your time, have your charts—paper or electronic—laid out where they are accessible, review and brief all procedures.

Conduct a briefing to yourself or whoever is with you. If you get in the briefing habit, you will find that it makes flying easier and safer.

You may not get any applause when you complete the landing, but you can feel the same feeling of satisfaction that the actor gets after giving a good performance.

Oh, one final word. Saying “standard briefing” is not now, nor has it ever been, a briefing. It is just a lazy pilot’s way of trying to brief without the bother of an actual detailed briefing. If you’ve been guilty of that, please reconsider.

If your flights are repetitious, and you find yourself saying the same briefing every time, remember that every flight is a clean sheet of paper. Even if you take off from the same runway at the same airport, something will be different.

The temperature, the wind, the traffic situation, the airplane gross weight or something else will be changed. See what is different and brief it.

There’s little that’s more satisfying than a successful IFR flight, where you flew the departure, the enroute phase, the arrival and the approach all exactly as you were cleared, then landed and reached the parking spot without scratching the aluminum or hurting anyone. Briefings help you do that.

George Shanks retired from a major U.S. airline. He now even briefs his drive to work to a corporate pilot training center in Dallas, Texas.