Most instrument trips end with one approach and one landing, after which you go about your day. For those times when one approach doesn’t result in a touchdown, the choices are: A second approach, or a diversion, hopefully somewhere with coffee and cookies. The common protocol is to decide that ahead of time, based on conditions and your own policies. But when the weather’s in that grey zone between IFR and VFR, there’ll be some choices that aren’t always clear-cut.

Making Tweaks

Grey indeed. It’s a misty, overcast morning preventing a bird’s-eye view of your scenic destination, Morganton, North Carolina. The airport of choice, Foothills Regional, offers services and lodging away from the busy metro areas of Charlottesville and Ashville. KMRN has a 5500-foot runway and RNAV approaches at both ends. There’ll be a north wind at arrival, so you plan Runway 3.

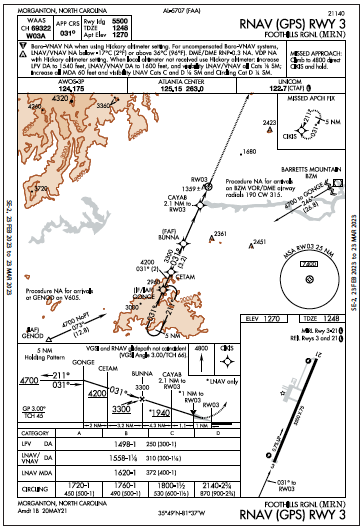

This will be the third vacation in the family four-seater since installing a WAAS GPS capable of LPV minima. Checking the weather, you think: Won’t need the fancy equipment today, but for reference, Runways 3/21 have LPVs. The RNAV (GPS) 3 has a DA of 1498 feet, with a mile visibility. The actual conditions will be closer to 1000-3—good for a comfortable approach. With decent weather in the regional forecast, it looks fine to file a nearby alternate, Hickory Regional to the southeast, with a tower, multiple runways, and not just coffee, but a restaurant.

The route from Greencastle, Indiana arrives from the northwest. The game plan: From the Holston Mountain VORTAC, head for the IAF, GENOD. With that transition labeled NoPT, you must skip the hold-in-lieu-of-procedure-turn at GONGE unless you need a turn (and get a clearance). Then, you intercept the final course from GONGE.

There’s a Visual Descent Point (VDP) on a one-mile final that you’ll brief in a bit. Coming in from the northwest at 9000 feet, the overcast won’t allow you to take in the Blue Ridge Mountains below, but maybe on the return flight. At any rate, ATC guidance will help with stepdown altitudes after the mountains and by the IAF, you can be at-or-above 4700 feet for the approach.

With terrain surrounding much of the inbound routing, you wonder: Why doesn’t this approach have a Terminal Arrival Area? Those are the handy blocks of airspace that give you obstacle-clearing altitude(s). The plan views present either a big circle around the airport or pie-shaped space for a T approach with base-to-final legs. All you get on this RNAV 3 approach chart, though, is a standard 25-mile MSA ring of 7400 feet. Recall that the Minimum Safe Altitude is for emergency reference, and will be just above the highest obstacles in that chart sector.

Here, there are transitional segments already drawn out from the southwest (GENOD) and the east/northeast (BZM) to provide safe altitudes to fly as you near the approach. Note that GENOD is an IAF, while BZM is not. It’s not to scale either, if you caught its distance of 26.8 NM to GONGE. Either way, the “Procedure NA…” notes on both sides means no direct-from-airway arrivals to the approach from those fixes, due to sharper-than-allowed turns. How does that work for GENOD? You’d need vectors or a re-route to get set up properly. You think of a simpler trick: Replace GENOD with GONGE on the flight plan as a hint that you’d like direct to the IF/IAF after HMV and use a teardrop entry to fly the HILPT.

The Catch

Now check out the Visual Descent Point one mile from Runway 3. VDPs, as explained in AIM 5-4-5, allow a stable visual descent below the MDA. That could be handy if conditions are as predicted and you break out of the clouds at around a four-mile final. And if the visibility is indeed at least three miles, you’d be able to proceed visually from there and get that landing in on one approach, then go about your vacation. But wait. VDPs are for MDAs, not DAs. The AIM makes it clear: “VDPs apply only to aircraft utilizing LP or LNAV minima, not LPV or LNAV/VNAV minimums.” Understood. You’ll be in visual conditions by then, and maybe even cancelled.

That might’ve been wishful thinking, because the morning instead brought ceilings of 400 feet overcast, visibility a half-mile in mist. Now that it’s below minimums for that LPV, it’ll require a wait of at least a couple hours, according to the forecast. When will it be safe to depart—when it’s 500-1/2 and improving? When it reaches the conditions you’d so carefully planned for yesterday, 2000-3? When it’s at published minimums? It’s a three-hour flight to KMRN, so you depart when the updated METARs for both the destination and alternate reach 800-2. Sure, you can file another alternate with better weather, but doing it this way nudges you toward a safer weather cushion. Besides, everyone’s eager to get going.

Indeed, you look like a genius when you pick up the AWOS from Holston Mountain: 2000 feet overcast, visibility two miles. You specify the approach with Center and get cleared direct GONGE, then the approach. After starting the final descent at BUNNA, though, you’re not feeling as brilliant because you think you oughtta be out of the clouds, but you can’t see forward and the ground contact is just a trace.

At the VDP, which you remind yourself is just a one-mile reference and not for the LPV, you see the PAPI’s faint glow through the mist. But you don’t see anything else, and it’s DA-plus 300 feet. Will you continue to the DA, or miss now? You know that you’re using the landing requirements under §91.175, which call for lights or markings to be “distinctly visible and identifiable.” A fuzzy PAPI (with no second item in sight) doesn’t cut it for you, so back up you go. Of course, as you zoom over the threshold, you do see the “3,” the stripes and even a few sets of runway lights. But it’s too late now, and within seconds you’re back in solid IMC.

Two for One

The missed approach is simple: Fly straight out to 4800 feet to the holding pattern at CIKIS. If only you’d reviewed it on the way; with so much fixation on the game plan, you didn’t cover all the approach-briefing bases. Here’s where the simple missed icons on the profile view saved the day and you manage to climb out flawlessly. A quick call to ATC above 2500 feet and you reach the holding fix, with promises to check back in after one circuit. That’ll let you decide whether to fly the LPV a second time (your policy is to never fly a third) or head now to the alternate.

While pondering this, you turn up the number two com to hear the on-field AWOS, which continues to drone its 2000-2 reading. Why the discrepancy? Two statute miles equals 1.737 nautical miles, so you should have seen the threshold more clearly from the VDP. Not necessarily. Foremost, what you see looking forward a mile from the field won’t always sync up with a digital readout on the field.

Read your Instrument Procedures Handbook lately? It explains Automated Weather Observation Systems, those typical stations found at airports with IAPs. They do have sensors located near the areas where aircraft land, and the readings get averaged over minutes and converted to the transmission you hear. Pulled out your copy of Advisory Circular150/5220-16E recently? This explains how the stations are certified and maintained, and there a table showing that acceptable margins can be up to +/- one mile in visual weather, down to 1/4 mile in low visibility. A half-mile for a two-mile report, for instance. Same goes for cloud layers, which are derived from sensors over a period of time to create cloud and ceiling reports.

In a final approach, of course, all that matters is in-flight vis of one NM or 1.15 SM, which could’ve met the legal minimum for the LPV if the PAPI was more clearly visible. As you fly the hold in fuel-economy mode, there’s time for one more circuit, one more LPV, and a diversion to the alternate for lunch. By the time you’re halfway around the second hold, the AWOS upgrades to three miles, and you get cleared back on the approach. You landed after breaking out into ground visibility two miles from the runway along with the “3” and some lights beyond well in sight.

It was surely easier, after the workload of a missed approach and hold, to have weather above your minimums to adjust the glidepath and land normally. Probably should’ve waited another half hour to depart, but you used the information available at the time. There wasn’t a backup plan per se for the second approach other than an alternate, but in this case the missed approach and hold worked out, buying enough time to wait for better weather while working out the tougher choices.

Elaine Kauh is a CFII in southeast Wisconsin. Most of the approaches she flies result in a landing, and all of them result in lunch or dinner.

Your current updates to the web sight are very good as I have found the More Stories and search more useful – faster returns of related information. It’s A Good Improvement. Thank You