How do you know when your nagging voice is just being a weenie and when it’s really onto something important? Here’s our take on what to ask and what to do.

It’s probably happened to you: Something en route made you consider not continuing to your intended destination. Now you’re faced with the myriad choices of why, when, where and how to divert.

Why?

The decision is easy when you’re 100 miles from your destination with 250 miles of fuel remaining and a line of level 5 “dragons” requires a 150-mile detour. Bad weather—between you and the destination or at the destination itself—probably tops the list of reasons for a precautionary diversion.

In most other circumstances, however, choosing to divert can be difficult for us Type-A, results-driven pilots. What if increasing winds have been changing your fuel projections from landing with an hour and a half of fuel to just under an hour, and the winds might get worse. Perhaps deteriorating weather at your destination is projected to go below minimums, but it isn’t down there yet. Maybe something on the aircraft is unusual—lower than normal oil pressure, perhaps—but not outside the acceptable limits. Maybe you or one of your passengers is starting to squirm but isn’t telling you yet.

Do you divert early in these situations, or try to make it? Good question.

When?

There’s a reason that airlines and professional flight departments have clear procedures and limits: It’s far easier and safer to imagine a situation and the proper response when you’re sitting at your desk than in flight. It’s best to pre-establish limits to aid airborne decision-making. Let’s see how that might look on some of these developing situations.

FAR 91.167 requires departing so that you’ll have 45 minutes of fuel remaining after landing at your alternate (if required) for IFR flights. I personally use one hour.

If I planned for an hour of reserve and have lost 15 minutes, I ask why. If the answer is a continuing condition, it means that I’ll likely have even less fuel and I will divert. If the answer is a one-time situation, such as a previous reroute, then I’ll continue, watching the fuel closely. If my projected fuel at landing falls under 45 minutes, it’s time to divert.

Deteriorating destination weather is tricky. The best system here might be a serious of honestly answered questions. Are you proficient, rested and at your best? Will the deteriorating weather permit a safe approach? Is your IFR alternate a realistic choice—in terms of weather, fuel and your state of mind when you get there?

If you can answer “Yes” to these, there’s probably nothing wrong with continuing with Plan A. Otherwise you should consider a change of plans. Identify these and other questions and the necessary answers ahead of time and decisions at altitude are easier.

Mechanical irregularity requirements can also be predetermined. If it is a single reading that remains stable within limits, I’ll continue. But if it’s getting worse, or multiple readings conspire to confirm a problem, I’ll land. (See the sidebar for a time I should have landed.) When in doubt about your craft, land.

You can also clearly set comfort limits. Say you’re getting your butt kicked in turbulence and a passenger requests a landing to avoid redecorating the interior of your airplane with his lunch. Even if the ride is getting smoother, that passenger is in distress and will thank you for landing or curse you for continuing. Same way with bladder requirements.

Here’s another way to think about it: If the need is strong enough that you’re considering landing, it’s probably worth landing. Remember that you don’t know what else Murphy will toss your way along the rest of the trip. You’ll have to to deal with that on top of the, uh, pressing need.

A reality check on this is comparing how soon you’ll realistically be on the ground by diverting versus continuing. Ten minutes to the final destination? A full bladder could probably wait that long, but not airsickness. If it’s an hour, though, better divert.

Where?

Picking the right airport needn’t be too difficult. If I need to land for fuel, I’ll hopefully figure that out early enough to have time for a little research to choose where to buy it.

A tip to the wise: Radio ahead and hear from a real, live person that there’s fuel available. Get FSS to call for you if need be. Just because the AOPA directory says there’s fuel doesn’t mean the self-serve pump is working or the FBO didn’t close 10 minutes early. I know a certain magazine editor who didn’t spent a night in Sidney, N.Y., because a local pilot happened to still be at the field and happened to have the FBO owner’s home phone number. Hint: his last name contains a “vehicle” and a “direction.”

For weather, mechanical irregularities or passenger comfort (including food, toilets, turbulence, etc.), I’ve concluded that any airport with a tower probably will do. Sure, there are some terrific facilities at non-towered airports, but unless you want to take the time to sort through the directory, a towered airport is nearly a sure bet for reasonable ground services like fuel, repairs, food, lounge, even nearby hotels and car rentals (although you may have to wait until the next day). Most of ’em will have a good approach, too, but it’s best to check just to make sure you’d be comfortable landing from what’s available

To select an airport, I look along my route ahead within the required descent time with another few minutes at cruise at the most. If nothing fills the bill in the available distance, I’ll look up to about 45 degrees left or right of my course. Rare is the place (in the U.S. at least) that this won’t yield at least one suitable airport from IFR altitudes. Obviously, charts, directories and the “nearest” function on your navigator will help a lot.

How?

If the weather is VMC, consider proceeding VFR. It’ll cut down on the complexity and give you a little quality alone time to plan your arrival.

In IMC, though, you’ll have to plan the approach. Depending on the time, this can be routine or a real nail-biter. The rule here, though, is to take the time you need. Remember, this is a precautionary diversion, not an emergency, so don’t get rushed by ATC into doing something you’re not yet prepared to do. You could even delay asking for the revised clearance if you need to buy a few minutes.

When time is tight, I’ll grab a piece of information I need (frequency, course, altitude, etc.) and use that to configure the plane, one bit at a time. This will give me a piecemeal briefing as I set up for the approach. It’s not as good as a full briefing, but good enough in a pinch. For a complete discussion of setting up for an approach at the last minute, see “Your Best-Laid Plans” (June 2012 IFR).

Call It a Day

Once you land, that inner Type-A pilot hiding in most of us will start thinking about departing again shortly.

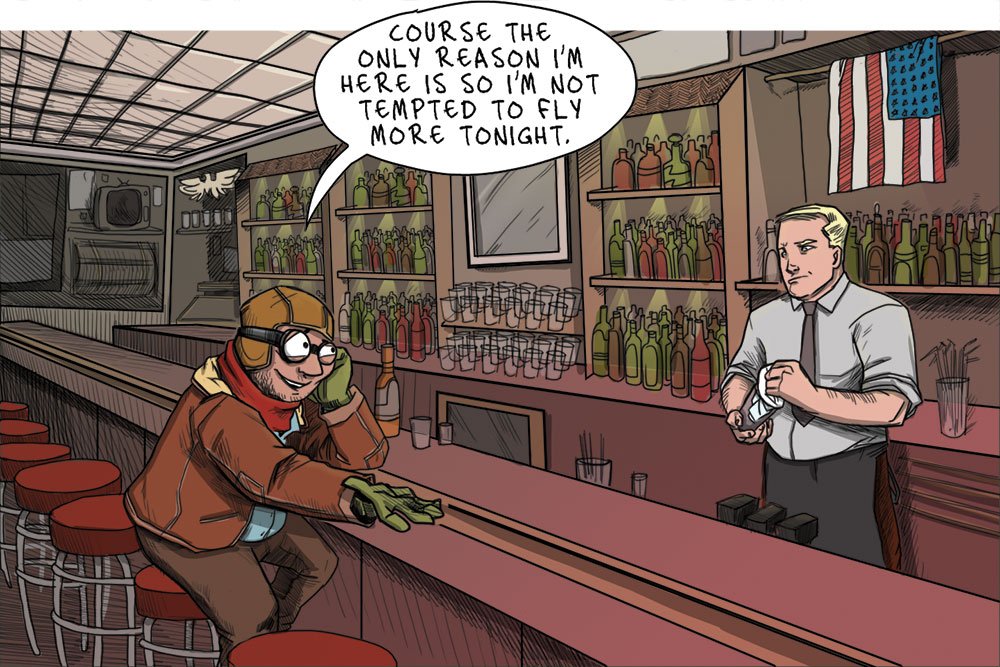

If the reason for the diversion is anything that makes me even consider hanging it up for the day (serious weather, waiting for a mechanic, turbulence, etc.) rather than sit there and stew over the possibility of continuing, I choose instead to head to the nearest bar and have an adult beverage. This eliminates the option to proceed no matter how tempting it may be. It’s also made for more than one extremely pleasant, if unplanned, overnight stop.

Excuse me mister, it looks like You’re Leaking Some Oil

We were returning from Oshkosh in our Mooney. Our first stop was Kearney, Neb., to spend the night with some friends. At cruise, I noticed that the oil pressure was just a smidge lower than normal. It was still in the green, so I decided to just keep an eye on it and continue.

As we flew, the pressure continued a slight decline. I also noted that the oil temperature and CHTs were a bit higher than normal. Foolishly, I pressed on.

Nearing Kearney, the oil pressure was just above minimum and the temps were just below maximum. Obviously, something was wrong, but the engine was running just fine. Besides, it was about time to begin the descent.

Reducing power in the pattern at Kearney, the oil pressure finally dropped out the bottom. I landed and parked at the friendly FBO. The lineman came up to the side window and said, “Uh, Mister, you’re leaking some oil.” I thanked him and got out to take a look.

The entire left side of the airplane was coated with oil, as if we’d just flown through a deluge of AeroShell. Oil was actually running (not dripping) off the tail tie-down. The oil cooler had sprung a leak and there was no oil showing on the dipstick. We replaced the cooler, filled the oil and checked the engine, finding no apparent damage. We dodged a bullet.

The good news was two-fold: We got to spend a couple extra days visiting our friends while waiting for a new oil cooler, and I learned never to dismiss what the gauges try to tell me. I should have diverted. —F.B.

Frank Bowlin has diverted for each reason stated. The decision gets easier with experience, and knowing which airports have nearby pubs.