Many sharp instrument students and pilots, when asked what items must be considered for an IFR departure, go confidently to Section L of the Terminal Procedures Publication, TPP, and talk about the Obstacle Departure Procedures, ODPs. This makes me confident they’re on the right track. But many will then either gloss over or improvise their way through the section on takeoff minimums. This information looks important, with restrictive numbers and climb gradients in it. Many CFIIs, though, just teach that it doesn’t matter at this stage. True enough, but knowing a little about them can help us make better departure decisions.

In all of Part 91 (outside Subpart K), there’s only one area that discusses takeoff minimums. Specifically, 91.175(f) is titled “Civil Airport Takeoff Minimums.” Part 91 pilots hoping for guidance are disappointed with the first sentence: “Unless otherwise authorized by the Administrator, no pilot operating an aircraft under parts 121, 125, 129, or 135 of this chapter…” Despite this fact, let’s play along and see what it is the for-hire folks have to do. If it’s good for them, there might be something there for us, eh?

Da Reg

I’ve always found the general way the regulations are written to be a little backwards, and this one is no exception. So, I won’t quote the actual language, but it essentially states that you must follow takeoff minimums outlined in 14 CFR Part 97, “Standard Instrument Procedures.” Lacking specific guidance there, the reg sets standard criteria.

Those minimums outlined in Part 97 are the takeoff minimums we see listed alongside the ODPs in Section L of the TPP and on Jeppesen’s 10-9 or the back of their first-sequenced chart. If no minimums are listed, the de-facto standard one-statute-mile visibility for single and twin-engine aircraft applies. (Although the FAA doesn’t use the word “standard,” we will.)

With no intended disrespect to those who fly aircraft with three or more engines, we’ll deal with the more common single- and twin-engine aircraft. Notice how the minimum refers only to a visibility, not a ceiling. This ties in with the FAA’s definition of landing minimums using visibility only with no mention of ceiling. If they want a minimum ceiling for departure, they’ll have to tell us about it in Part 97.

So, absent any further restrictions takeoffs require one statute mile visibility—or 5000 RVR, if available—regardless of the ceiling. If the FAA determines that’s not enough, they’ll establish “nonstandard takeoff minimums” as discussed.

Hill-Country Example

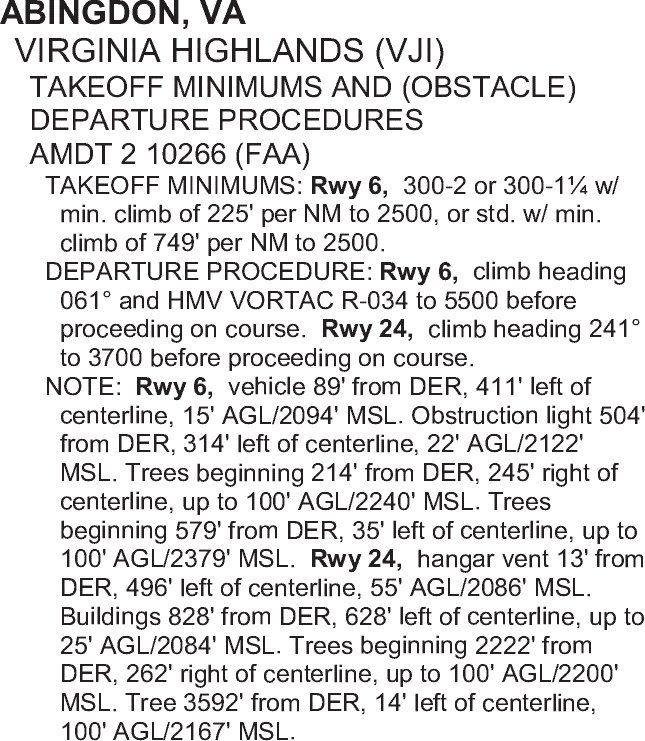

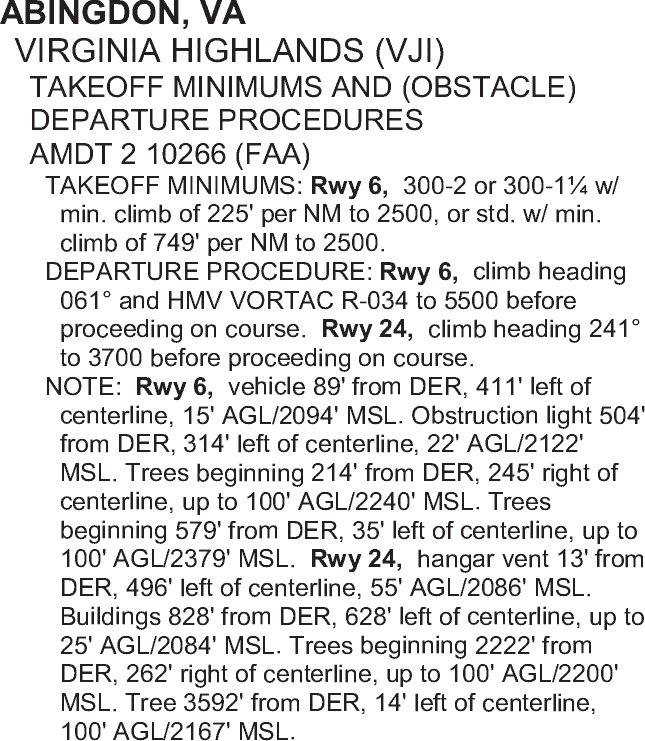

Let’s look at the Virginia Highlands Airport. With “Highlands” in the name, you can bet on special TERPS criteria for takeoff. Runway 6 has terrain and obstacles off the departure end, so it has nonstandard takeoff minimums. The absence of restrictions for Runway 24 means that the standard applies. We need to closely examine Runway 6 takeoff minimums since it has both ceiling and visibility restrictions listed.

The first nonstandard takeoff minimum listed for Runway 6 is a 300-foot ceiling and two-mile visibility. So this is an additional mile of required visibility and establishes a ceiling requirement of 300 feet. But “or” listed in the takeoff minimums tells us there’s an alternate—perhaps easier—way to meet the requirements. The “golden ticket” that relaxes the takeoff minimums comes from a higher-than-standard climb gradient.

Runway 6 gives us two choices, each with successively steeper climb requirements. The first restriction allows us to slightly reduce our 300-2 limits down to 300-1 if we can climb at 225 feet per nautical mile to 2500 feet MSL. The next lets us use standard minimums, but requires a 749 feet per nautical mile climb gradient.

The climb/descent rate tables show that at 90 knots groundspeed this more restrictive climb is over 1100 fpm, and at 120 knots groundspeed this will be roughly 1500 fpm—no small feat. Using 300-1 only requires about 340 fpm and 450 fpm at 90 and 120 knots groundspeed respectively. All this tells us there are obstructions off of the end of Runway 6 that the approach/departure designers want you to be able to see and avoid visually, or climb well clear if you can’t see them.

Yeah, So?

The basis for establishing nonstandard takeoff minimums comes from FAA Order 8260.46D, “Departure Procedure (DP) Program.” It essentially says that if there’s an obstacle you won’t clear with the standard 200 feet per nautical mile climb gradient above 200 feet above the runway, they must establish ceiling and visibility minimums sufficient for you to see it, or require climb gradients that assure you’ll miss it. That’s a pretty good plan if you think about it.

TERPS may dictate establishing these criteria, but 91.175(f) applies them to certain commercial operations. But, just because they don’t apply to you for a Part 91 flight doesn’t mean you can safely ignore them. Chapter 1 of the Instrument Procedures Handbook clearly weighs in on this, stating: Aircraft operating under 14 CFR Part 91 are not required to comply with established takeoff minimums. Legally, a zero/zero departure may be made, but it is never advisable. If commercial pilots who fly passengers on a daily basis must comply with takeoff minimums, then good judgment and common sense would tell all instrument pilots to follow the established minimums as well.

Yeah, But…

We’ve all seen commercial aircraft depart in less than one-statute-mile visibility. So, what’s up with that? As the Instrument Procedures Handbook explains, many operators are permitted per their Operations Specifications (specific FAA guidelines on who, what, where and how that commercial operator may fly) to conduct lower-than-standard takeoff minimums. Many times they may use the required landing visibility for a suitable approach back into the departure airport. Other operators can take off with 600 RVR or less if the airplane is equipped properly.

In all lower-than-standard takeoff situations, two things will apply. First, you must be trained (and often checked) in the performance of a lower-than-standard takeoff (which needs to be documented). Second, per 14 CFR Parts 135 and 121, any time you conduct a takeoff in visibility lower than required for an approach back into the departure airport, you will need to list a takeoff alternate—selected the same way as a landing alternate—within one hour’s flying time of your departure airport.

Here are the takeaways for takeoff minimums: Understand that one statute mile is the standard minimum visibility requirement for takeoff. If obstructions off the departure end require visual identification or a steeper-than-normal climb gradient to avoid, there will be nonstandard takeoff minimums listed in Section L of the TPP or on the appropriate Jeppesen page, and you would be prudent to adhere to the listed restrictions.

If you choose to depart with less than the required takeoff minimums, understand that such operations are not recommended by the Instrument Procedures Handbook, and commercial operators require special training to do so. Also, any time a commercial operator departs an airport that is below landing minimums, they must select and list a takeoff alternate within an hour of their departure airport. Following these commercial operators’ restrictions is a wise risk-management strategy.

Evan Cushing is a former regional airline training captain who now works in a collegiate flight program, where his minimums are strong coffee and a few books.