Setting up for the expected approach when you’re 30 minutes out is simple. It’s handling those last-minute changes to a different approach that tests your mettle.

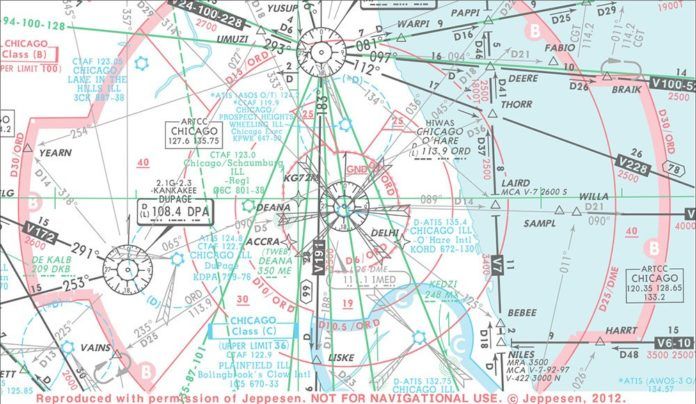

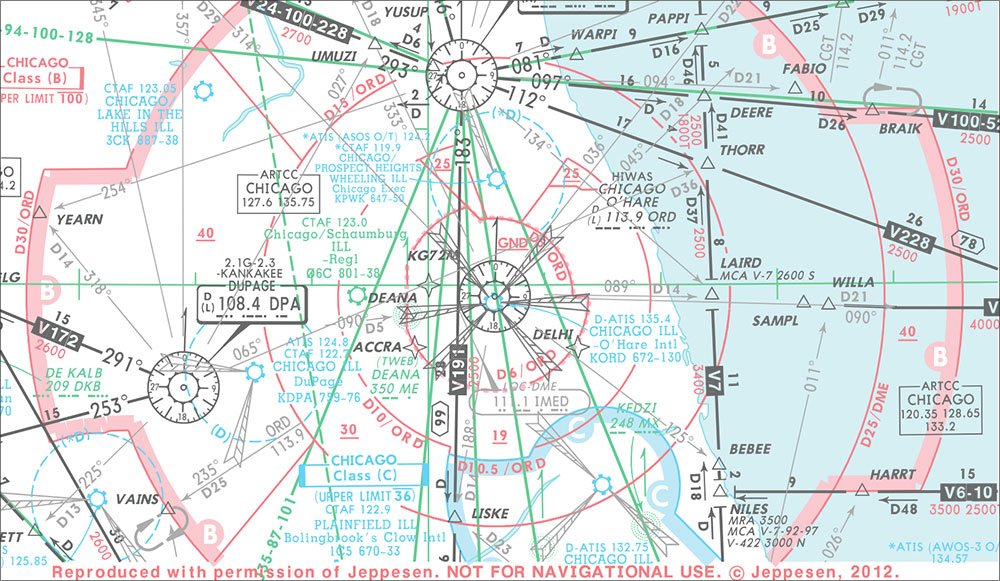

I wanted to cry. It was my Initial Operating Experience for the jet after transitioning from a turboprop and we were going into O’Hare. In a snowstorm. During rush hour. We’d just gotten our third approach change. I was so lost that I was little more than a voice-activated systems interface for my instructor pilot. If my brain had any spare cycles, I’m sure it would have been thinking about truck-driving school.

Over drinks that night, I vowed I’d figure out how to handle the worst the ORD controllers could give me. Last-minute approach changes are just part of the game, and I needed to flesh out this part of my playbook.

In Command

Rule number one for the pilot trying to be flexible is that you shouldn’t accept anything you don’t think you can handle safely. As PIC, you’ve got to be like Kenny Rogers: know when to hold ’em and when to fold ’em. Sure, you want to work with the system and go with the flow, but don’t forget who’s got the controls and who’s just watchin’. You telling ATC “unable” is best if you can’t be ready to nail the approach.

But playing the “unable” card has responsibilities. Don’t just say, “Unable.” Instead, add something like, “I’ll need vectors back out and a few minutes to set up for this new approach.” Believe me, no matter how much trouble that might be for the controller, it’s way better than the mess you might make in his airspace if you try to comply with a hurry-up approach, fail, and need to execute a missed much later in the process.

Bait and Switch

The approach change I dread the most is what I call the “secret change.” You got the ATIS, briefed, and set up for the advertised approach. On your first check-in, they tell you to expect the same. You’re ready.

They vector you around for the approach. With perfect situational awareness (yeah, right) you might get a hint of a new plan by noting that the vectors don’t quite match what you’re expecting, but you figure there’s traffic or something. Then, you get cleared for the approach—a completely different one than you have set up.

We humans being what we are, there’s a danger in hearing what we expect to hear, rather than what actually came over our headsets. Be sure to listen closely to approach clearances in particular, as they are prime for this trap. (And if you do accept the change, be sure to un-key the mic before you besmirch the controller’s ancestry.)

More often, ATC will give you some warning while you’re getting vectored around. You’ll have some time to prep the new approach, but probably not as much as you would like. How much time is enough is a question only you can answer.

Setting Limits

Sitting at home in your easy chair is a good time to think about limits. When do you think you can accept a new approach, and when should you decline? For me, that limit with an autopilot is at least a minute or more until I’ll have to do anything besides follow vectors. If I don’t have an autopilot, I’d want several minutes, longer if it’s not smooth, clear air. As these kinds of switch-ups often happen around busy airports, don’t count on too much help from ATC other than some delaying vectors for time.

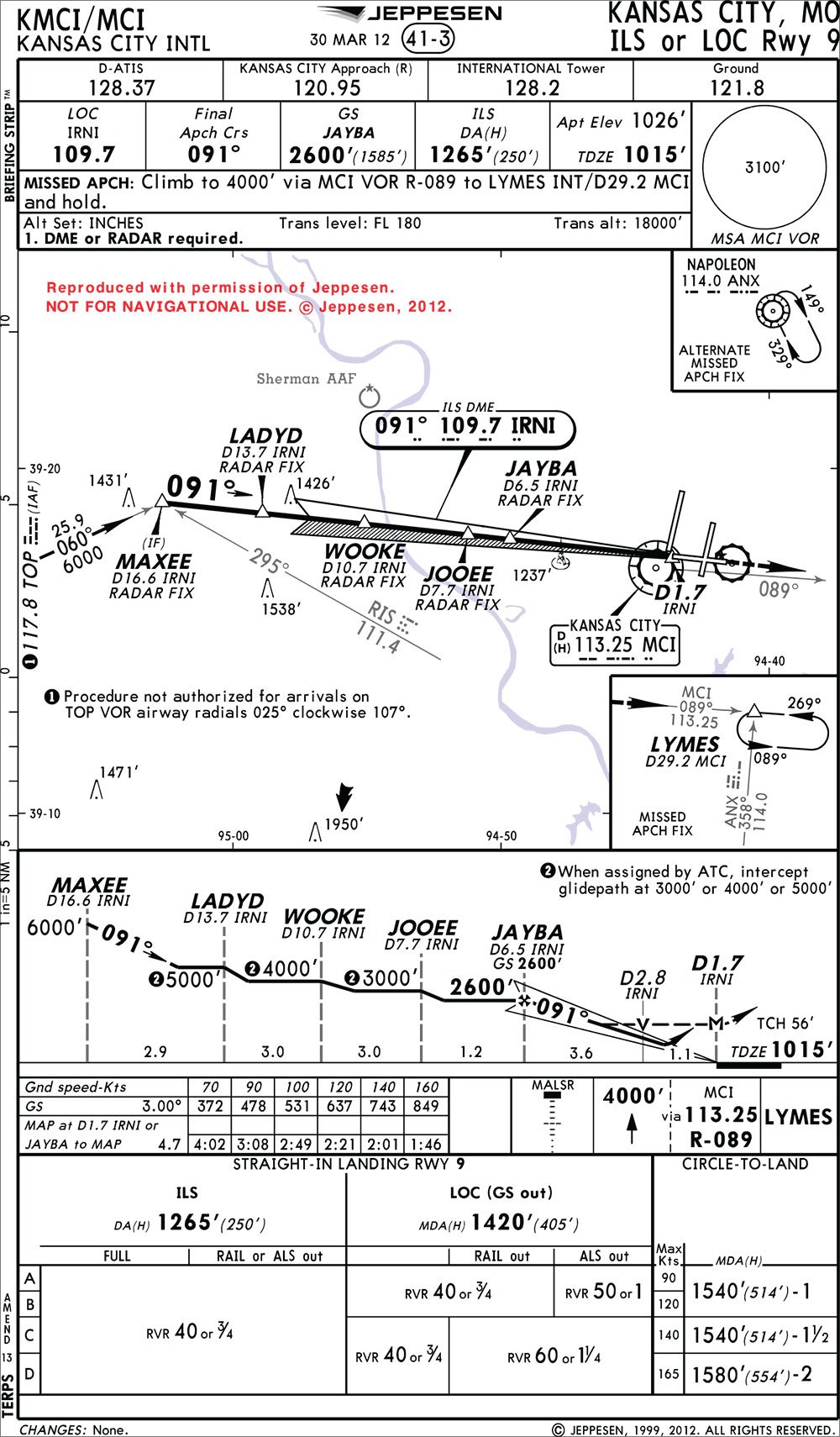

How much time you need varies depending on the new approach. You might be planning the ILS to one runway and they’re just sliding you over to the parallel. No brainer: Change frequencies and you’re pretty much ready—you can do that with no more than a few seconds notice. Approach will often even give you the new frequency. On the other hand, if you’re set up for a GPS overlay for the VOR approach and the weather is dropping so they give you an ILS instead, you might need a closer look.

Everything you need to successfully execute an approach can be categorized as either information or configuration. The information includes frequencies, altitudes, descent points, MDA, MAP, missed approach procedure, etc.

Configuration is getting the radios and instruments to match the information.

When time is tight, I choose the process of getting the piece of information I need and then use that to configure, one at a time. This comprises sort-of an ad-hoc, piecemeal briefing along the way—not as good as the real thing, but it’s sufficient in a pinch.

Things like MDA and MAP are critical data, just not yet. Some folks get anxious not knowing the MDA/MAP early on. Before I get too concerned about what might happen at the end of this approach, I first spend my time figuring out how to get there.

What do you really need to be set up for an approach? To get started, there are only three pieces you need right away: the frequency (or GPS approach setup), the next course and altitude, and the point at which you can descend to it. That’s it.

Priorities

Your priorities will have as much to do with your equipment as your skill level, whether you’re trying to fly that approach with a tired KX 170 or the newest GTN 750. The nav/com is easy to set up; the full moving-map GPS takes a bit longer.

If the new approach is predicated off ground-based equipment, you’ll need a frequency. Got charts? I don’t care how easy it is to look up a different chart on that electronic wonder in your panel or on your lap, if you’ve got paper, it’ll likely be faster to flip a page or two and note the frequency. Or, even better, ask ATC, if there’s enough dead airtime. Enter it into your VHF nav and set the course. Done. Next. (Oh, yeah: Identify the frequency at some point.)

Case in point: I recently went flying with a friend. The weather was deteriorating. We had expected a visual, but really needed the ILS, so we weren’t prepared. He spent the next couple minutes trying to enter the ILS into his navigator and set it all up for the pretty picture. Meanwhile, we were about to cluelessly blow through final.

Instead, he first should have just tuned in the ILS, switched to green needles and set the course. He’d have been ready for the intercept in a few seconds. If time permitted, he could then configure the rest of the magic at his leisure for the advisory-only, supplemental, pretty pictures.

Setting up an approach using GPS navigation is more complex than just looking up and tuning a frequency. You’ve got to find the approach, load and activate it and, in some cases, dial in your course. That’s gonna take time. If you’re really fast, you can probably do it in less than 30 seconds, but if you’ve got to fumble around, even just a bit, you’re probably looking at a minute or more.

The next thing I’d look at is the approach itself. Where am I relative to the final approach course? What’s my turn to final? Some might argue that you should be looking at altitude first to see if you can descend before reaching final. My reasoning is that you can die if you get the heading/intercept/course wrong, but you’ll only be embarrassed if you are too high on the approach.

Get the heading/course squared away before devoting brainpower to altitude.

With that bit of information gleaned, the configuration comes from setting up your brain and, if applicable, your autopilot, to do the intercept or the next turn. (Note I said brain and autopilot, not brain or autopilot.) If you’re hand flying, be prepared to manually accomplish the turn, the right direction and to the right course. In a hurry, we tend to fall back to old habits. Be sure to get the course and turn direction right.

If this is a GPS approach, it’s easy from here. Just follow the pretty lines, keeping the needle centered and, if you don’t have an electronic HSI, turn the OBS as/when instructed.

Now we’re ready for altitude. The information you need is the minimum altitude for your segment. Configure yourself to be there as soon as practical. What’s the next altitude, and where does it begin? (More information.) If equipped with altitude pre-select or an altitude alerter or even just a reminder, enter the next altitude as soon as you’re level at the current one, and start down a tenth or two before hitting the descent point. (More configuration.)

Somewhere along the line you should have a moment to take a broader look at the approach, making a mental note of the MDA, MAP and missed

approach procedure. Do it when and where you can, but be sure to get it done. Now you’re briefed.

Down the Pipe

Although certainly stressful, accepting and properly executing an approach that you’re given at the last minute can be done safely, as long as you keep a few things in mind.

Have a clear idea of your no-more-changes point and be willing to insist on more time. Use your autopilot to free up brain cycles even if you had been hand-flying for the fun or proficiency; this is not the time to be proud. Use the information/configuration process combined with the approach overview when you have a chance for a high-point approach briefing while assuring that you and the systems are able to fly the plan. Continue down the pipe like this until you see the runway and squeak it on.

Sure, a change at the last minute isn’t as good as a relaxed, full, approach briefing before you begin your initial descent, but it’s good enough to keep you from having to fold ’em or think about that truck-driving school. Kenny would approve.

Detect and correct (or exclude)

I’m old school. Way back when I learned to fly, the newest thing on the panels of our trainers was a space-saving new box that would let you both talk and navigate, just not at the same time. Pretty cool stuff.

VHF nav was simple and still is: Just set the right frequency and course and reference the CDI. Errors were usually obvious—the CDI is flagged because it should be 108.3 MHz not 108.5 MHz. More subtle errors could be caught by an ident or a needle indication that just made no sense. (When that’s all you’re looking at besides the flick in your head, you pick up on these things.)

Now you can enter a fix name and it will take you straight home from anywhere. But if you get it wrong, it will take you about 10,971 miles in the opposite direction just as easily. Or, you can enter the entire approach, as long as you carefully select the exact one you need from a potentially long list.

Unless you’re flying a GPS-based approach, you really don’t need to configure that fancy navigator at all. But if you have time, you should do so as one of the last priorities because if you don’t, there is one great big gotcha to keep in mind.

Raise your hand if you’re one of the few who recognize the value of a real DME and still have one. Good. You’ve got accurate distance information. If you use GPS in lieu of DME, the trap of a fast-change approach is that your GPS is still showing distance information to some other waypoint, possibly on some completely different approach. Ignore GPS distance information unless you’ve set up your wonder-box for the current approach. —F.B.

We’re not sure if it’s by design or not, but the newish Garmin GTN 650 puts an unsuspend button where the distance would be when you’ve still got the opposite-direction approach loaded. These are the RNAV 34L and ILS 16R at Everett, Wa.

Frank Bowlin avoids O’Hare whenever possibly. When he has to go there, he can handle a few changes now without crying.