Why do holiday newsletters begin with, “It’s hard to believe another year has passed”? Have we not yet accepted the earth’s orbit around the sun? Or is it truly unfathomable that no matter what reality dictates we’re doomed to repeat the same dumb things year after year? And I’m not just addressing you folks in Washington, DC. It’s easy to ignore signs of catastrophe while hoping for positive results. The Chicago Cubs could win the World Series but only when we pilots quit reenacting the absurd.

Each year we scour the NTSB accident/incident reports, seeking those aviators who’ve come spinner-to-spinner with stupidity and never blinked. This time we examine 2010, but it could be any year. Non-fatal cases only, each ripped from the investigative funny pages of apparently uncorrectable errors, such as loss of directional control on landing, largely attributable to lack of crosswind capability—the pilots’, not the airplanes’. Balloonists continue to grab power lines and offload passengers prematurely. Ag pilots plow into low hanging fruit, and some of us will never figure out how to manage fuel.

New Year Resolutions

Praise the optimists with New Year resolutions to fly every day and make each flight seem as though it’s their last. Which it almost was for a Texas pilot and two passengers who launched January 1 on a night cross-country in a Maule guided by 21st century stars. When the GPS constellation failed them they reverted to 1950s radar vectors to their destination. Nearing that, the pilot could not activate the pilot-controlled airport lights—Click, click, click, click, click (Huh?) Click, click…

Lights work better when you’re clicking the right frequency. Undaunted and unable to spot the 1940s aerodrome beacon—that was NOTAM’d out of service—the pilot diverted to another airport 45 miles away but slightly beyond the Maule’s fuel supply. After the engine quit, the pilot and passengers deplaned in a ditch to reevaluate nighttime fuel reserve requirements (it’s 45 minutes, not 45 miles) and New Year resolutions.

You just gotta love a Maule. These backwoods four-seaters have earned a reputation for boldly going wherever the imagination demands. Common sense, however, doesn’t always ride shotgun. Witness the Colorado Maule pilot and companion who were “flying along a creek looking for a place to land and go hiking.” Not so unusual; folks out West routinely do this, and as often happens with pilots watching the ground they tend to run into things. In this case the pilot “thought he had struck a tree.” They then flew 17 miles to a private airport and stuffed the mauled evidence into a friend’s hangar.

“Anyone asks, you know nothin’, right?”

Weeks later someone asked. Seems the Maule had snagged a power line 35 feet above the creek, severing the left aileron, which caused the property owner below to alert authorities, who must’ve followed the bread crumbs to the clandestine hangar.

Can you imagine the pilot’s response when the investigator mentioned the missing aileron? “Really? No aileron? Hmm…however could that have happened?”

Not to be outdone, a VFR Maule pilot in Utah took off in low visibility for a local flight, which, indeed, stayed local as he recognized his poor decision-making prowess and landed on a road only to nose over in a snow bank. The nearest weather reporting station called the ceiling 200 feet with 1/4-mile visibility in fog.

Mind you, this sort of folly happens with inspiring panache in Alaska, where a commuter pilot in a Cessna Caravan departed Kwigillingok with seven passengers in the cabin and a trace of ice from freezing fog on the wings. At 200 feet the pilot experienced a “series of power fluctuations,” which caused the aircraft to descend as the pilot “engaged the emergency power lever.”

That sounds so cool. I wish my Aeronca Champ had an emergency power lever.

Alas, the leveraged power emergency wasn’t enough, and the icy Caravan stalled and smacked a frozen lake, damaging its right wing. Thankfully, it was winter or the seven passengers who’d set sail that day, would’ve been in for a swim…the skipper, too.

Departing with contaminants on the wing, in violation of the limitations section of the airplane’s flight manual supplement, might’ve made for a ripping yarn in the lower 48, but this being Alaska, the Caravan lifted off and landed at another village with an equally unpronounceable name. Hey, the Iditarod doesn’t celebrate the serum almost getting through.

If you can’t handle adventure then stay in Iowa, where a non-instrument rated pilot contacted AFSS for a briefing: Thank you for calling VFR-Not-Recommended Service; how may we misroute your call? Press or say, “One,” for a wet tarp on your VFR plans…

While we don’t have access to the actual transcripts, the NTSB reports that AFSS told the VFR pilot that IFR conditions were forecast for the next few hours, after which the ceiling might improve to 2000 feet. The pilot showed good ADM (Aeronautical Decision Making) and sat out those few hours before showing questionable judgment by departing VFR later without an update briefing—at least none that the NTSB could find.

Once airborne, the pilot received radar flight following and told the controller that he planned to land for fuel short of his destination. ATC acknowledged that and issued the weather at the fuel stop: IMC. So, the non-instrument-rated pilot did what any non-instrument-rated pilot might consider doing in that situation.

No, not turn back. He pressed on until finally realizing that, unlike in Jake Hollow adventure novels, the sky doesn’t always open up at the last moment to save the hero. Our VFR pilot requested vectors to an ILS after telling ATC that although not technically an instrument-rated pilot in the traditional sense of possessing an instrument rating or knowing how to fly on instruments, “he had practiced ILS approaches during a flight review,” perhaps at the Holiday Inn last night.

Dang, that’s practically like real IF&R, so down he goes through the clag, riding the localizer like a horizontal pole dancer but unsure how that glide slope needle worked. Did needle high mean that the airplane was high or the glide slope was high….?

Prang! The Cessna landed two miles short of the runway with only minor injuries to the pilot but substantial damage to the airframe. On the bright side, many New Year resolutions include getting that IFR ticket, so at least this pilot could log some real in-the-clouds time toward that goal.

Luck supplanted good sense for another non-instrument-rated Cessna 172 pilot who departed VFR but found himself stuck above the clouds over Ohio. Having read somewhere that ATC issues clearances to penetrate the overcast, he called them and was asked if he was qualified to fly instruments to which he replied, “You bechya!” And ATC cleared him into the icy soup.

Yeah, ice. What’re the odds of picking up ice in clouds over Ohio in February? The pilot had been briefed twice on the ice possibilities earlier that day, had received icing updates en route plus icing PIREPs from ATC.

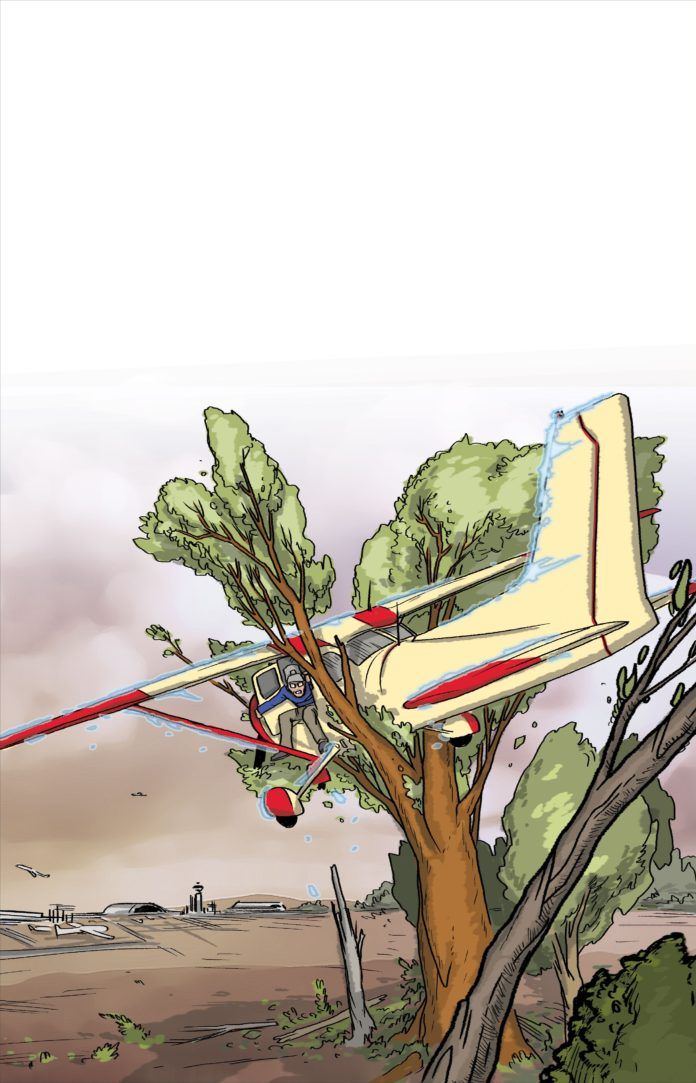

The non-instrument-rated pilot flying the Cessna not certified for flight into known icing conditions—and, cousin, this was known—picked up so much ice that he diverted to a closer airport. ATC cleared the Cessna for an instrument approach. Breaking out of the clouds, the pilot must’ve sighed a got-away-with-it grin and cancelled IFR, before dropping the ice-laden 172 into the trees 1/4-mile short of the runway. Doh!

White Out

Generally, we ignore student pilot errors, because they’re so darn adorable, porpoising down runways or landing at airfields miles from the intended destination. Well, most students get a pass. Not always, though…

Imagine this Montana student pilot’s surprise when approaching a frozen lake in a Bell 206B helicopter for what should have been a routine landing for those who routinely land on frozen lakes, except the ice was covered with 24 inches of snow. Soft snow. The kind that swirls in the hurricane whirlwind of the copter blades reducing visibility to the point where the pilot was just along for the ride as the hovering snow blower settled and rolled over.

One slightly odd element to this accident was the report listed two people onboard, both uninjured. That anyone could walk away from this crash was odd enough. But if that was a student pilot at the controls, why was there a second person on board? If this person of interest was a flight instructor, then who’s really at fault? No matter, lesson learned. Yer gonna make a great chopper pilot one day, kid.

From Amarillo, Texas to Frozenbutt, Maine, pilots spend a good portion of winter sliding off runways after testing whether that nil braking action report was really valid. That’s what happened to the Mitsubishi MU-2 pilot who landed 20 knots too fast at Amarillo, where the ice covered runway braking action was reported as nil, and promptly did a Peggy Fleming triple doughnut down the runway before coming to a stop in the frozen weeds with the right gear leg missing and three passengers squealing, “Wee! Do it again, Daddy!”

A Cessna 182 private pilot in Washington didn’t need two feet of snow or a field condition report to impress his three passengers. He simply picked a “remote, seasonal airport” that—because winter wasn’t the correct season—was NOTAM’d closed and unattended with a half-foot of powder where the runway should’ve been. Perhaps if he’d been flying a more bush-like Cessna 180 taildragger on skis he might have escaped into anonymity, but as the 182’s nose wheel found the snow it dug in and flipped the Skylane onto its back. Picture the passengers hanging from their seatbelts and wondering, “Why, again, did we land here?”

Warm Weather Foibles

Warm weather and having a flight instructor onboard doesn’t eliminate the risk of making it into this article, especially when CRM (Crew Resource Management) goes to pot as happened to the Piper Seminole crew on a training flight in Oklahoma in June. While the winds were sweeping down the plain, the flight instructor and student completed an instrument approach and intended to do a touch-and-go. They nailed the touch part, but during the landing roll when the instructor called for flap retraction—perhaps not a good idea—the student, instead, retracted the gear. A millisecond of disbelief preceded the instructor repositioning the gear handle to DOWN. Too late. Squat switches be damned, the nose wheel collapsed, and the light twin slid off the runway like a dead tuna down a pitching deck.

And then there’s the Arizona flight instructor who, while demonstrating soft field takeoff technique in a Piper Archer to a student and backseat passenger, incorporated departure stall technique into the lesson. Luckily, the stall occurred at 20 feet AGL, so there wasn’t enough room to develop a spin. The Archer’s left wing hit first, and with fuel spilling from the ruptured tanks the NO SMOKING sign remained lit as the occupants stepped clear of the lesson. This is why flight instructors get the big bucks.

And The Winner Is….

It’s a tie. The judges couldn’t agree on who gets the coveted Snatching Stupidity From The Jaws Of Prudence award this year. Two finalists both exhibited the willingness to expand the envelope beyond reason to make it to the top. We’ll report the facts and let you decide this year’s winner.

Finalist #1 was almost home in his Piper Dakota over Nevada when he spotted a friend’s car on the road below. Being Nevada, it would’ve been downright unfriendly not to say hello, so the pilot entered a descending Stuka dive to strafe the car. Recognizing that this game of chicken might be getting out of hand, he began to pull up but not before the Piper’s gear struck the car. The pilot then landed on the same road, perhaps to offer his friend a ride. Wouldn’t be right to leave a buddy in the desert after smacking him with your airplane.

Right or just stupid, the Dakota’s wing caught a roadside berm, possibly because the left gear leg had been sheared off in the flying clown act mishap. Whatever the cause, it became clear that no one was going home in that airplane. Good thing the pilot’s friend was there to give him a lift in the slightly dented car.

One state away in Idaho, Finalist #2 was a team act with two aircraft. This accident could be attributed to dumb luck rather than stupid intent. A flight of two airplanes was headed to the same airport. The Cessna 185 arrived first and overflew the snow-covered runway while the pilot queried a ground crew about the runway condition. The ground crew reported that the runway was snow covered but in “excellent condition, smooth and well compacted.” Something else was about to become compacted.

The 185 landed uneventfully and rolled to the end to await his wingman’s arrival in a ski-equipped homebuilt FK1 STOL (mid-wing, two-seater).

Have you ever been skiing when you stop to watch some hotdog barreling toward you, and there comes a point when you realize that there’s no way the klutz is gonna stop? Yeah, like that here.

The Cessna pilot stared helplessly as the FK1 landed and didn’t slow much while skiing uncontrollably into the Cessna, causing enough damage to strain any friendship.

That’s our review of 2010, and while pilots will find new ways to keep the NTSB amused, in 12 months we’ll once again wonder where another year has gone and ask why pilots still crash airplanes, and the Cubs still can’t make the playoffs.

IFR editor emeritus Paul Berge writes and flies in Indianola, Iowa. He hasn’t yet found his way into our annual review of pilot antics, nor does his Champ have an emergency power lever.