We espouse always being ready to miss an approach no matter how much we expect to land. How about being ready to call it quits only minutes after we enter the clouds?

After a long weekend at the cabin with the family, you’ve packed up the flying family truckster for the Sunday afternoon return from Rural Island Muni back to Bigtown International. Passing through 1000 feet AGL, you push Direct-Direct to re-center the GPS route and turn on course—no obstacle departure procedure from this uncontrolled field—when the engine stumbles badly.

It recovers before you can even act, purring smoothly as you roll out on course still climbing, but everyone heard it and all eyes anxiously await your decision. It makes a second hiccup—or was that just a normal skip you hear now and again? The eyes widen.

Do you go back to the Island Muni, which has only a GPS overlay approach? Get vectors to the nearest bigger field with a tower and facilities? Or do you just soldier on to the big city?

Not an easy decision, but one made tougher if you haven’t laid the groundwork first. We don’t usually think about what it takes to abort a flight after five minutes because we so rarely need to. But given how fast the workload can ramp up for a rushed approach, it’s worth considering adding this to your IFR practice.

Departure Alternate

Just as all IFR flights require an alternate airport when the destination falls below certain weather requirements, commercial and charter operations must specify a departure alternate in certain cases. This isn’t a bad idea for Part 91 flying, either; and we have more flexibility on where that airport might be.

In many cases, our departure alternate would be a return to the same airport we just left. But that might not always be the best choice, or even a viable one. The simplest reason not to return IFR is that the weather is low and the departure airport lacks an instrument approach. I know pilots who simply won’t depart a rural airport with no approach of its own if the weather is low IMC. I can respect that, but it’s not my policy.

I’m good with the departure if there’s an airport within 45 minutes with weather above approach minimums (or VFR). My logic is that the odds of an emergency so critical I can’t go 45 minutes before landing, yet not so critical I’m abandoning shooting an approach altogether and just spiraling down over the field via GPS, is so unlikely that it doesn’t warrant scrubbing a flight. What’s more likely is a situation that’s not life-threatening, but I want to get back on the ground to deal with. That might be the longest 45 minutes of my life, but I can take the stress for less than an hour.

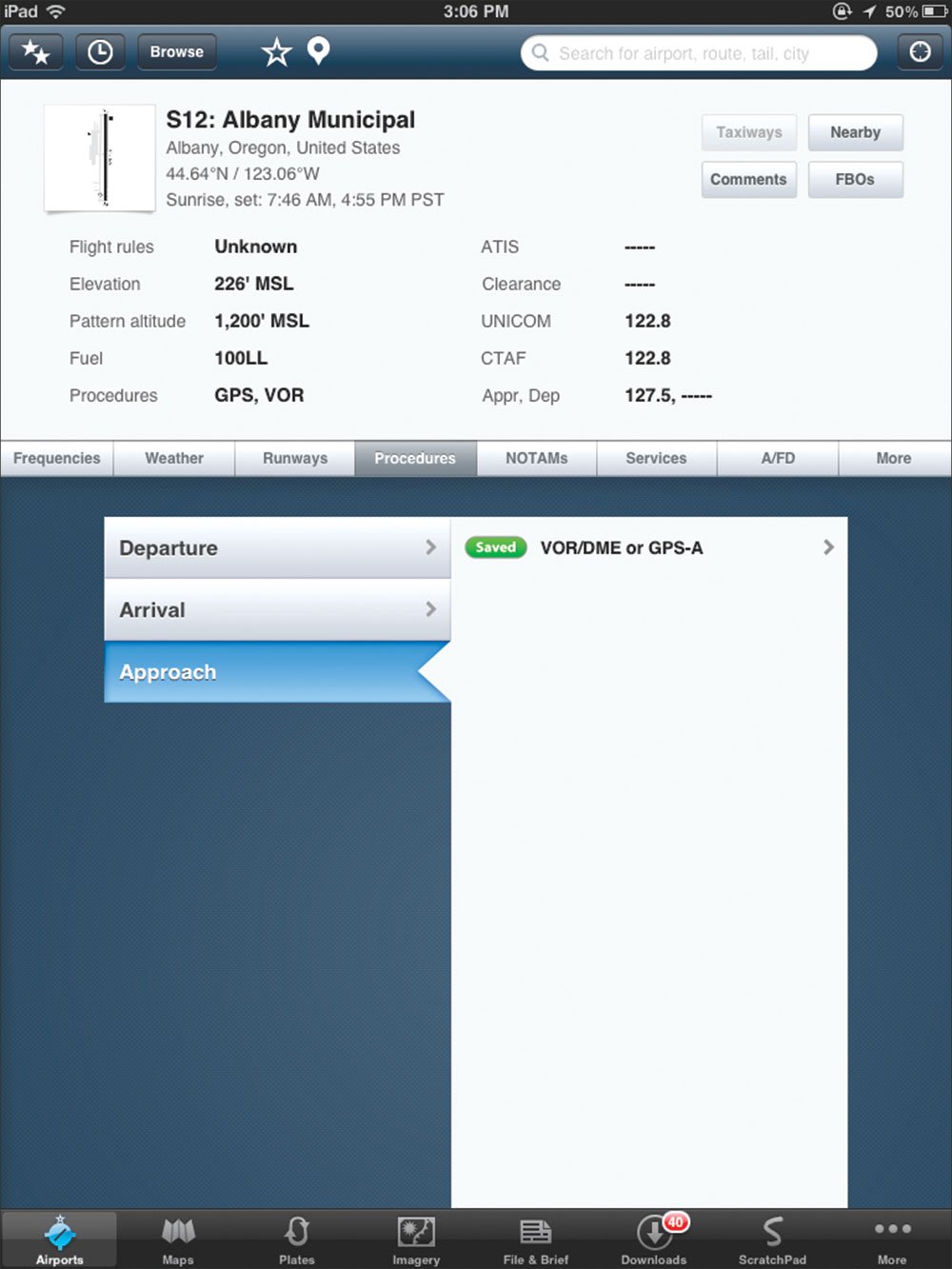

Another possibility is when the departure airport doesn’t have the best instrument approach for the situation. Imagine a northbound departure from an airport that has RNAV approaches to its east-west runway. You could return to the east-west field, but you’ll have to fly away from it for 15 miles or so before getting on the approach and turning around for another 15 or so back. If there’s an airport 25 miles north on your planned departure path with an ILS to a north-facing runway, that’s actually a “closer” airport. Even if it’s 50 miles away, it still might be a better choice. Regardless, it’s better to choose in the comfort of the FBO rather than under stress in the cockpit.

The point is that you should look at the big picture and pick something that best fits that day’s combination of weather, aircraft, available options and your planned route of flight. There might be no perfect option: There’s a good departure alternate 20 minutes away, but opposite your planned direction of flight. It’s up to you to decide where the balance is between mission completion and risk aversion.

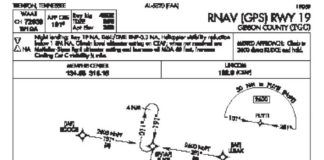

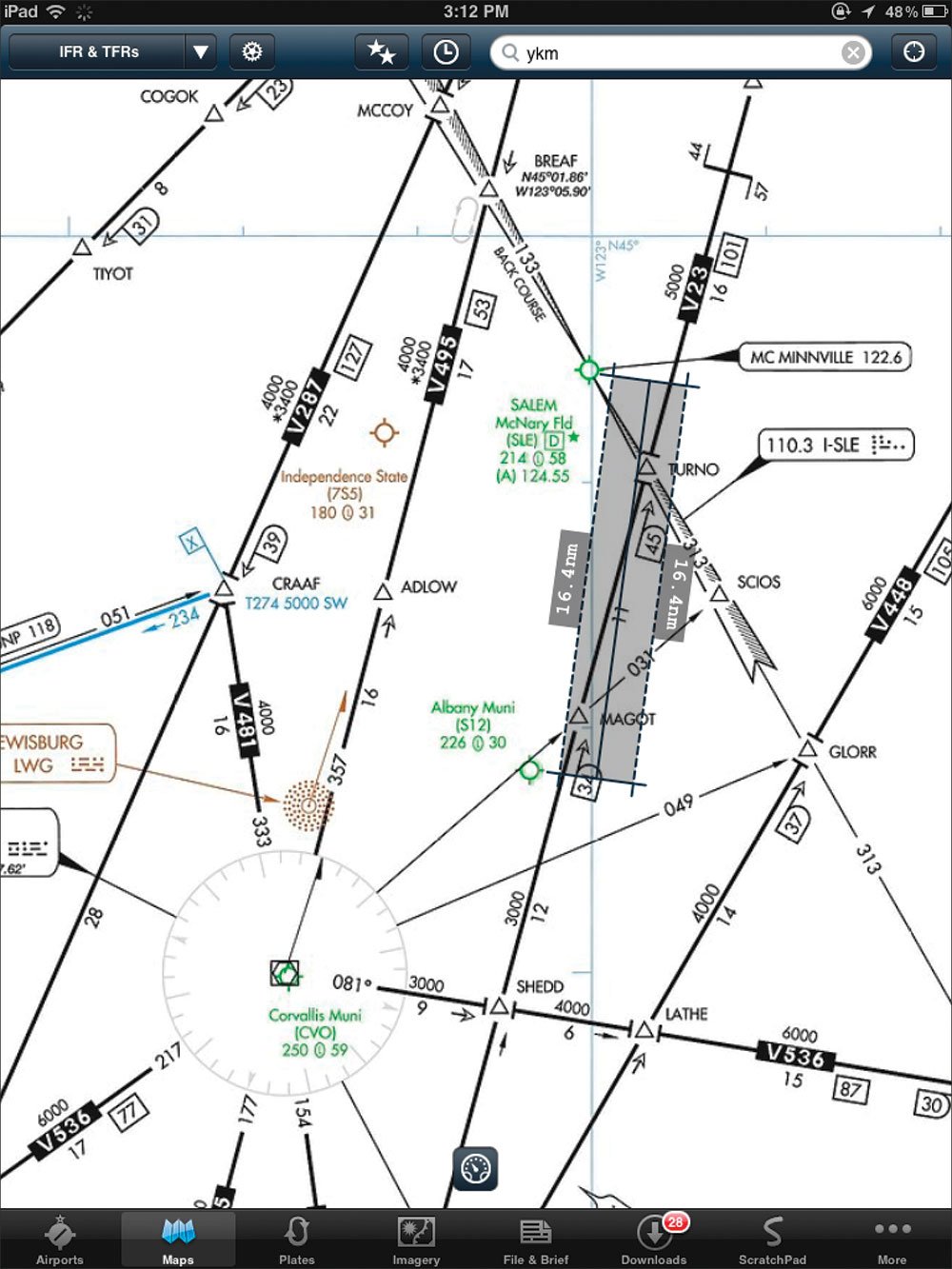

It’s also your call as to when you bother with a departure alternate at all. If the idea is new to you, it’s worth thinking about on every flight just to get comfortable with the process. My own standards are that if ceilings are under 2000 feet AGL, I at least have a plan for getting back even if that’s GPS direct to the field and spiraling down. If the departure field is IFR, I have a departure alternate ready. That might be just the local localizer dialed up in standby frequency for vectors back, or it might be a loaded approach to some nearby field.

Line Up and …

The next step after getting a plan for a departure alternate is deciding how much to prepare the cockpit for executing that plan. After all, odds strongly favor never executing this plan so you don’t want those charts in your way or those procedures in your GPS instead of the departure and route you almost certainly will fly.

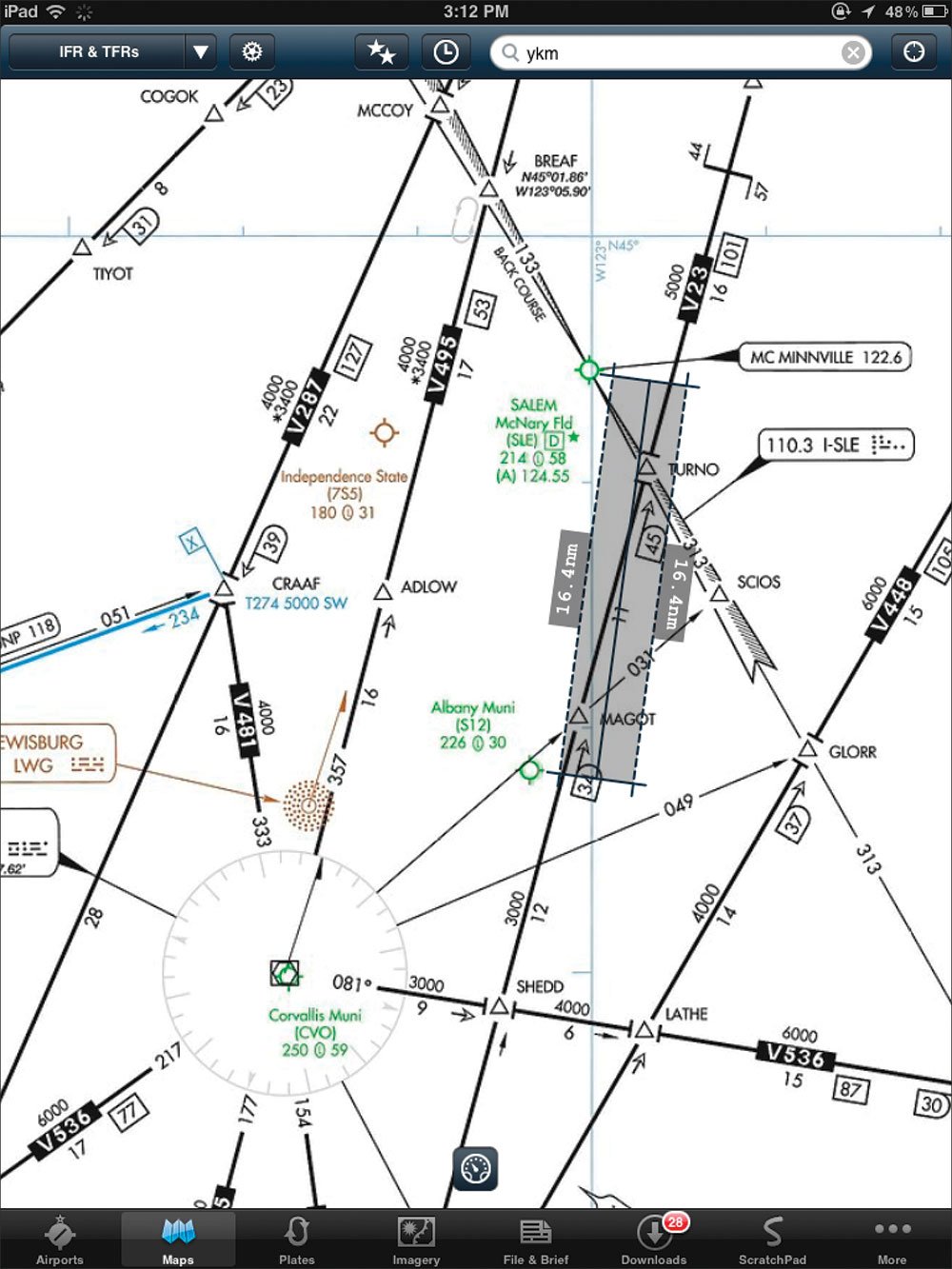

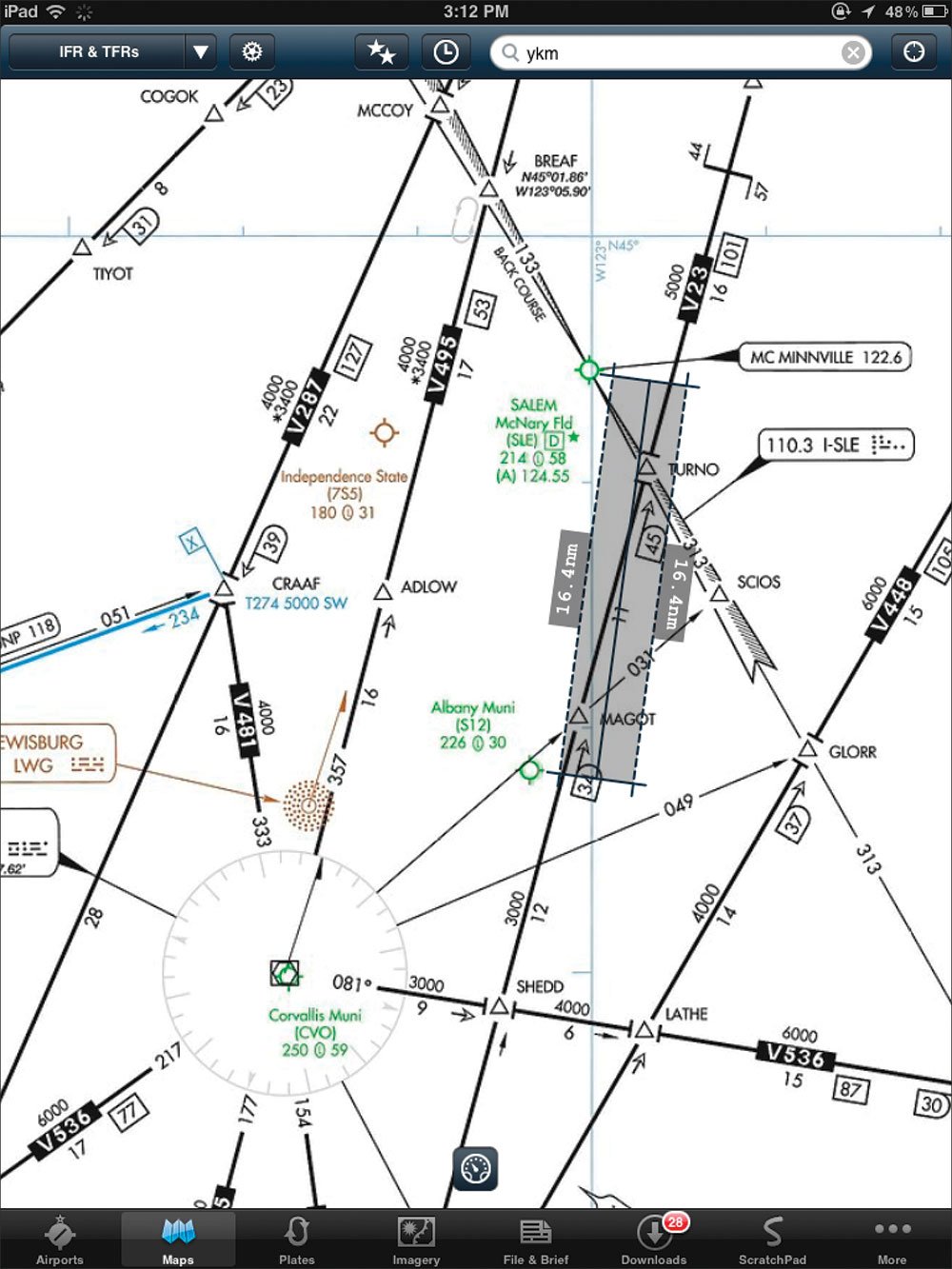

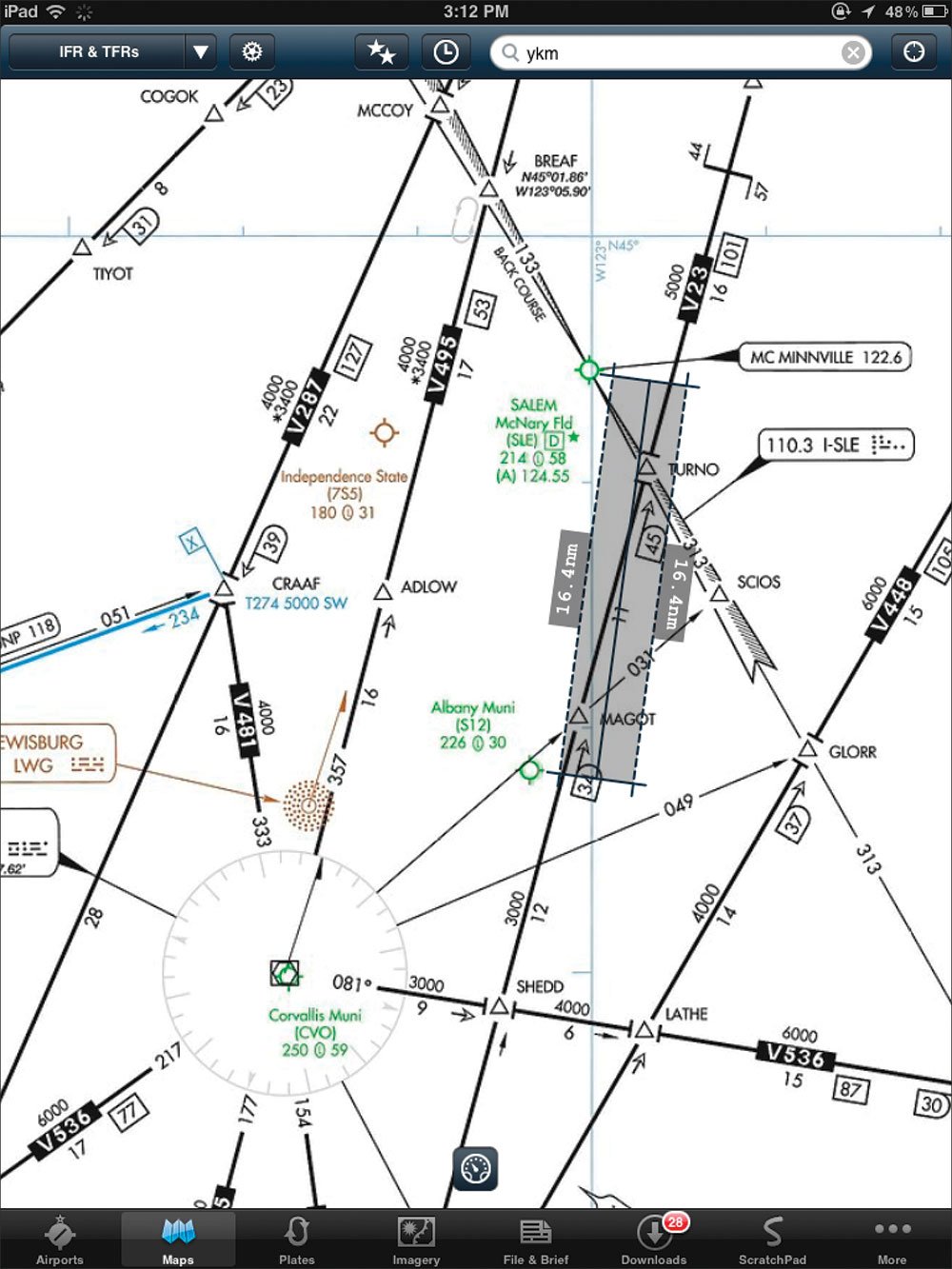

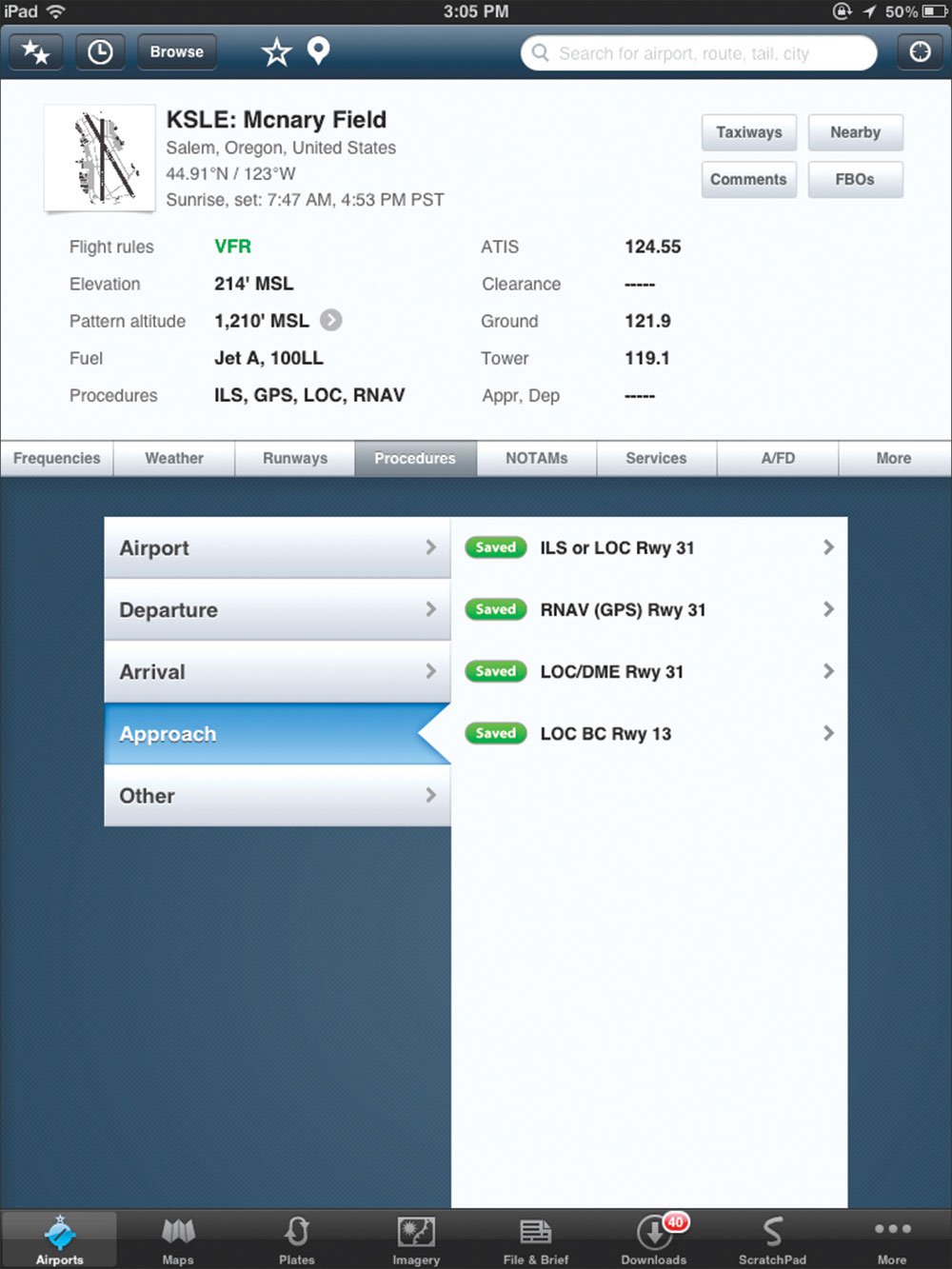

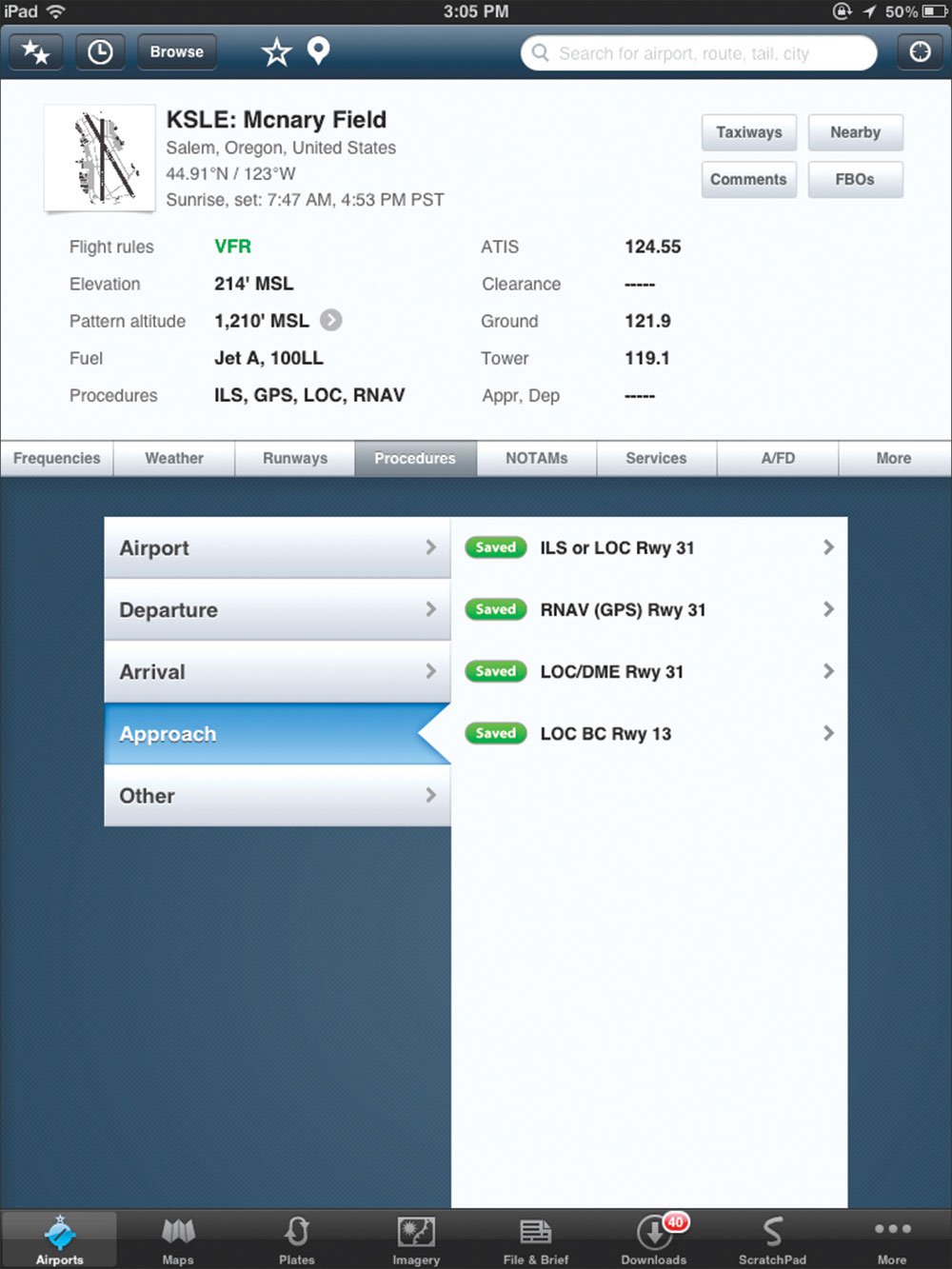

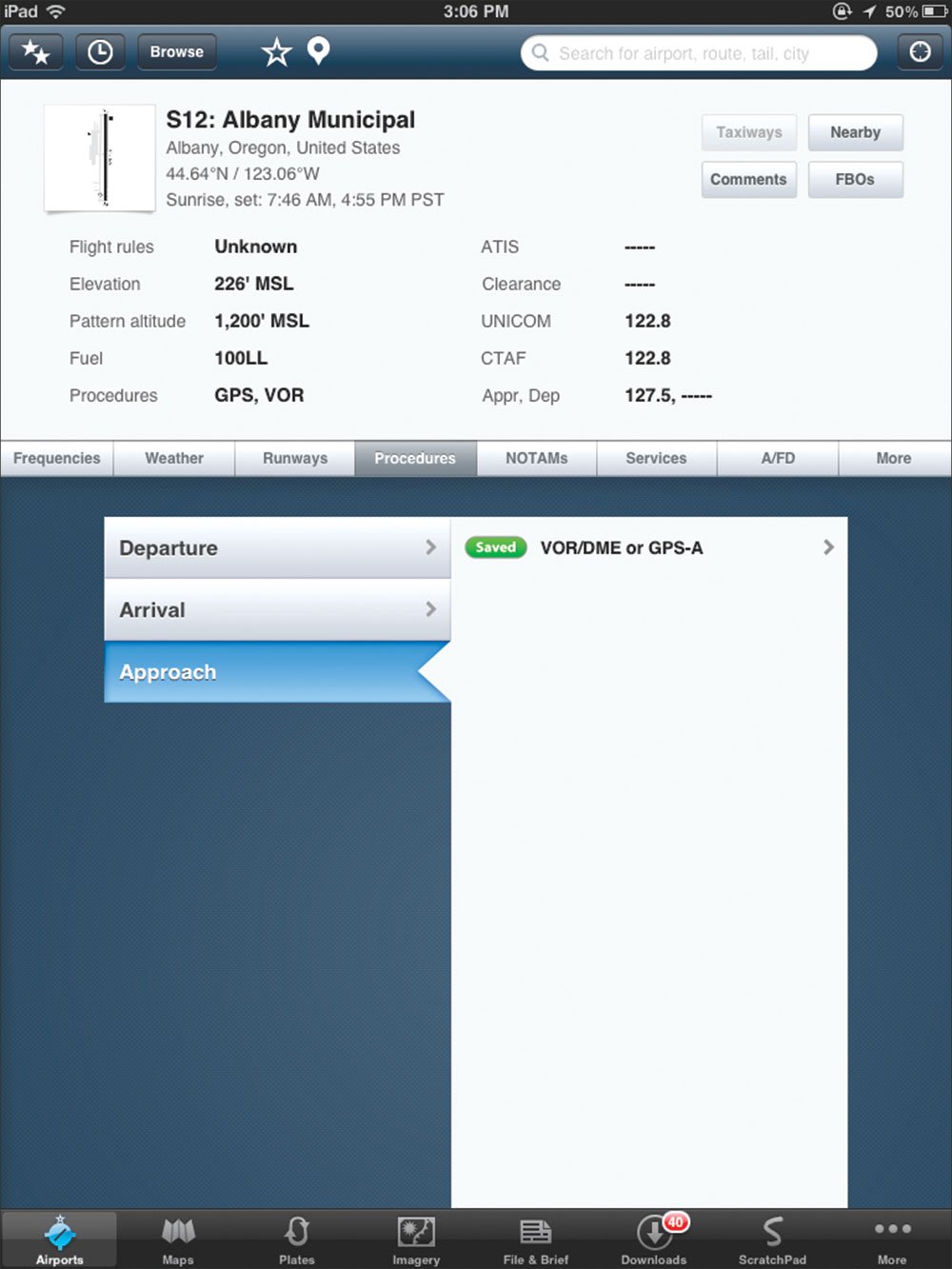

The right amount of preparation is a personal choice and varies with the situation. As I mentioned above, if your abort plan is simply returning to the same runway on an ILS, you may need no more than having the frequency in standby and a sticky note on the page in your approach book. (Sticky notes don’t work so well on the iPad, so having the approach preloaded on a screen is a good ploy. A less-known feature of ForeFlight that’s great here is creating a custom group of charts on the chart tab for your departure alternate. Delete it when you no longer need it.)

Setup is a bit trickier if your plan requires loading a GPS approach. You’ll want your navigator programmed for the planned flight, not the departure alternate. Still, there are solutions. One is that if you need an emergency return, you can select the airport at the top of your flight plan and make a direct-to. This often lets you load an approach for that airport right away. Note that in some cases, you may need to clear the flight plan to choose an approach at the direct-to destination rather than the flight plan destination.

Another option is reversing the route in case of emergency. This puts your departure airport at the destination end of the flight plan. That should let you quickly load an approach for your (new) destination.

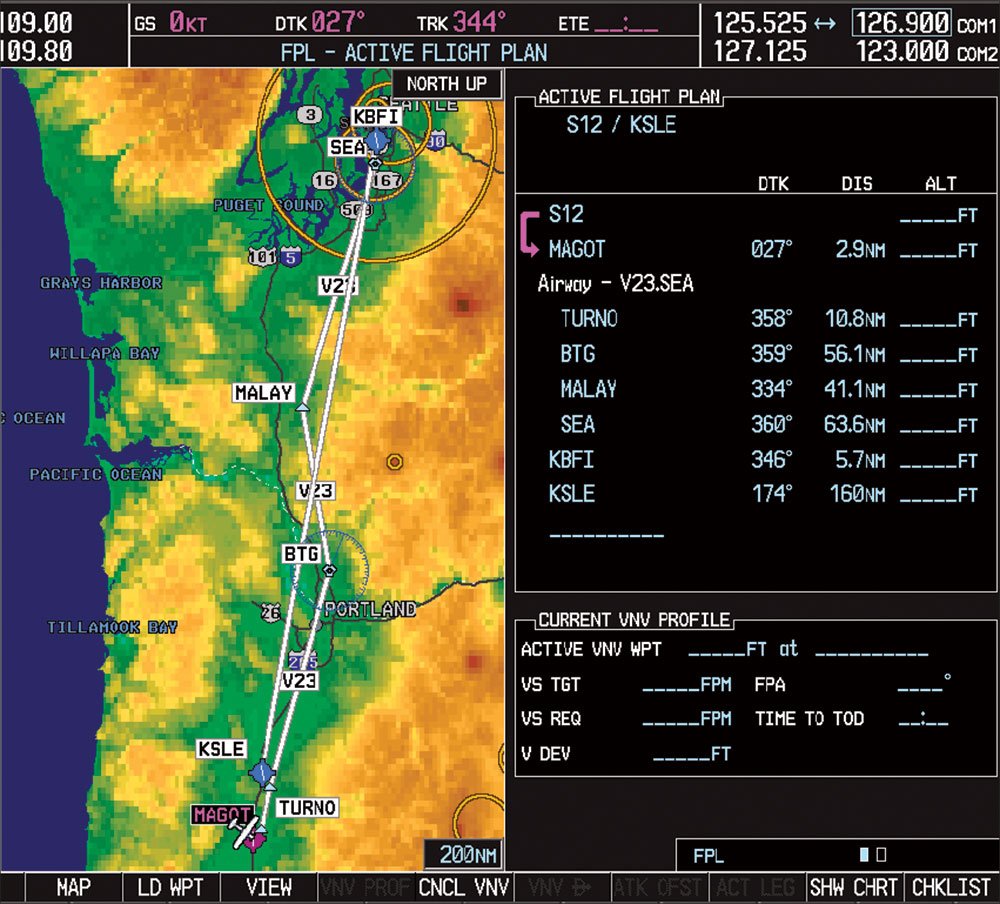

However, these methods don’t work if your departure alternate is a different airport than you’re actually departing. If you’re lucky enough to have two GPS navigators, you can have the approach at your departure alternate ready to go in the backup GPS, crossfilling or switching your CDI source as necessary if you need it. Creating a second flight plan for the departure alternate also works. Change flight plans if you need to bail out and land early.

Another option is to tack your departure alternate onto the end of your real flight plan. If you need to load an approach, the navigator usually picks the airport at the end, so voil, you get the selection of approaches you need by pushing the PROC key, but get the planned navigation otherwise. You simply delete that last waypoint once you’re up in cruise flight and don’t need it any more. Note that in this scenario your route is temporarily twice as long as you really plan to travel and you may see insufficient fuel warnings until you delete that waypoint.

Personally, I like the two-flight-plan or alternate-at-end set up, as it works even if my alternate is not my departure. Pick one and practice executing it. If you need it, you may be under a bit of stress and you don’t want to add more stress while fumbling.

Consider presetting anything else useful for an IMC departure. For example, I like terrain shading up on at least one moving map when I’m flying a G1000-based system on an IMC launch. Then relax and enjoy your planned departure knowing you have a Plan B if you need it.

We Have a Problem

So, when do you need it? Assessing emergencies is an article in itself (See “Just Do Nothing,” November 2010 IFR), but taking a play from that handbook, it can help to immediately ask yourself if this is an emergency situation or an abnormal situation.

True emergencies require immediate action. If the engine sputtered and then failed completely on takeoff, that’s an emergency—and you don’t have even the option of shooting a real approach back to an airport. Sudden low oil pressure would also count. You might have time for an approach, but I’d probably exercise pilot authority and self-vector with a GPS for a really tight return, as the engine could fail at any time.

The other extreme might be unusually high oil pressure or the wind and whine of a popped-open door. The plane is not in immediate danger—the situation is just abnormal—but you might want to return to the ground rather than troll on for several hours with a known issue. It’s likely you can take your time and execute your departure alternate plan unhurried, however.

Don’t underestimate the impact of a minor failed system. One January night in a light twin I and the other pilot on board realized the aircraft heater had failed while climbing out of Medford, Ore. We knew the plane and knew we could return and probably fix this recurring problem, but that meant an approach we weren’t set up for. We just decided to tough it out to Seattle. At 12,000 feet above a cloud deck, we had temps of -45 degrees C and no heat. We were practically brain-dead and zombie-stiff by the time we let down and shot an approach. (Some might say we started the day as brain-dead zombies, but I digress.)

Going back to our rough-engine scenario, it’s clear that making the call on returning to the field isn’t always a clear choice. I’d call a intermittently rough engine with no signs of imminent failure an “abnormal.” I’d watch the indications like a hawk, but proceed for that departure alternate presuming I would have engine power for the whole thing. More stumbles might change my mind.

But a plan means I could make a corrective action with less time lost fumbling and more confidence. And that’s bound to be a source of relief for everyone on board—myself included.

Jeff Van West might still have a few white spots on his toes from that flight out of Medford. He cringes when he hears the name “Janitrol.”