It happens thousands of times a day. A tower controller instructs, “Cleared for take-off, fly heading…” Most launch and turn to the assigned heading. A controller told me to do it so it must be safe, right? Maybe…

JO 7110.65, covering Air Traffic Control, is clear: “The primary purpose of the ATC system is to prevent a collision between aircraft operating in the system and to provide a safe, orderly and expeditious flow of traffic…” The order is written with those goals in mind.

Pilot responsibilities differ from a controller’s. The regs state, the “pilot in command of an aircraft is directly responsible for, and is the final authority as to, the operation of that aircraft.” This authority and responsibility is granted with the intention that it’s used to ensure safety—a pilot’s primary obligation.

Yet, pilots keep having controlled flight into terrain (CFIT) accidents, often with fatalities. It’s the second leading cause of commercial aviation fatalities worldwide. NTSB Board Member Robert Sumwalt described CFIT as “the problem that never went away.” CFIT frequently occurs at night or in IMC.

Instrument pilots understand terrain clearance requirements on approach and when enroute. Issues arise when controller instructions conflict with procedures that keep us away from the rocks. This frequently happens on departure and can get you into trouble.

Departure Basics

There are a couple of ways to join the enroute environment. The easiest is when you’re in VMC and maintaining obstruction clearance is as easy as looking out the window. Cleared direct to a VOR? No problem: take-off and head that way.

Just as easy is an airport without an obstacle departure procedure (ODP) or standard instrument departure (SID). In this case a 200- foot-per-nautical-mile climb, the standard climb gradient, keeps you clear of the obstacles.

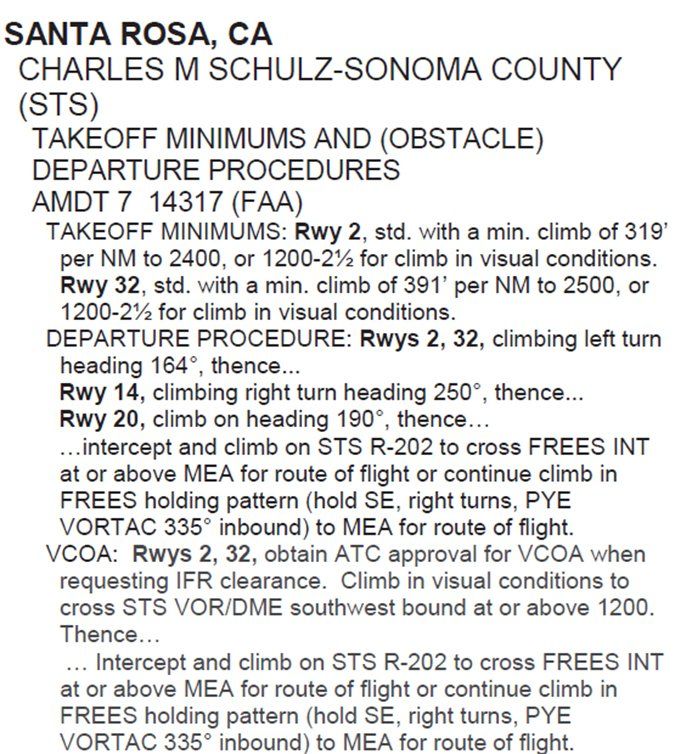

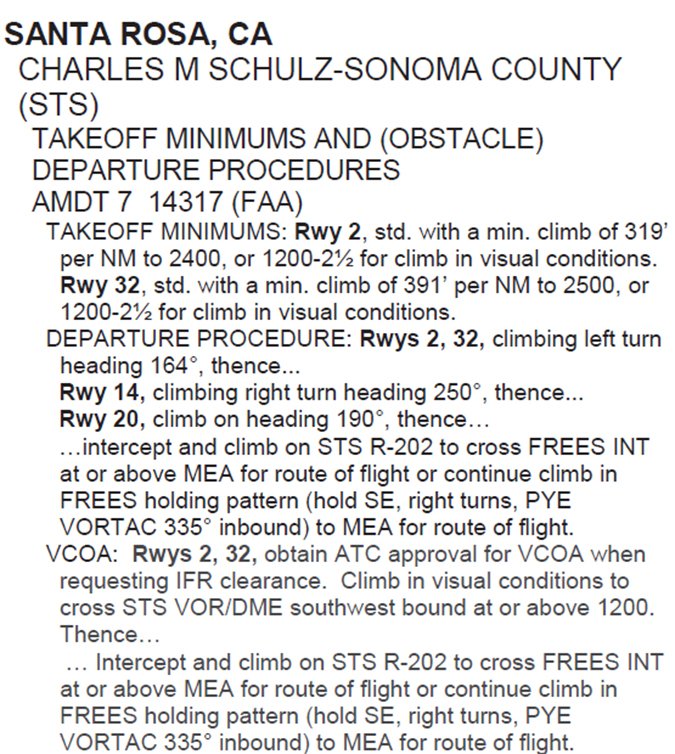

Things get complicated when ODPs and SIDs are thrown into the mix. An ODP is created when obstacles encroach on the 152-foot-per-nautical-mile obstacle-clearance slope. ODPs can be really simple, like climb to 1000 feet before turning right, or complicated, like this one from Santa Rosa, CA (KSTS): “Climb on heading 190, thence intercept and climb on STS R-202 to cross FREES INT at or above MEA for route of flight or continue climb in FREES holding pattern (hold SE, right turns, PYE VORTAC 335 inbound) to MEA for route of flight.”

While ODPs only keep a plane away from obstacles, SIDs serve two masters. They keep an aircraft from obstacles and help ATC sequence traffic. SIDs come in two flavors; pilot navigated and vector. In a pilot-nav departure, the pilot navigates the departure off of the ground. The FREES8 departure in KSTS (shown on page 17) is an example.

Vector departures require ATC to vector an aircraft to intercept a course or transition fix. For example, the ERRTH6 departure in Detroit Metro instructs a pilot to “climb on assigned heading for RADAR vectors to intercept…”

Complicated Stuff

Flying frequently isn’t as clear cut as our training or books suggest. Dark corners, unexplored in training, occur at the nexus of the differing priorities between ATC and pilots.

Problems can be illuminated by exploring a couple of scenarios. We’ll take an instrument flight out of Santa Rosa, California (KSTS). Santa Rosa is a Class D airport nicely situated between the Napa and Alexander valleys, home to some of the best wines on the continent. After a weekend getaway with your sweetie, it’s time to load a couple cases into the Cessna 172 and head home.

Winds are out of the south. ATIS reports Runway 20 in use. Calling up Ground, you’re cleared for the FREES8 departure, which is great because it’s straight out and only requires a standard climb gradient.

Pulling up to Runway 20, Tower says, “Cleared for take-off, turn left heading one-five-zero.” What to do?

Most would just turn to the heading. The astute might even check that departure had radar services using the logic that tower was providing a radar vector. In both cases, you’re getting set-up for a CFIT.

The ATC order states that “compatibility with a procedure issued may be verified by asking the pilot if items obtained /solicited will allow him/her to comply with local traffic pattern, terrain, or obstruction avoidance.” [Emphasis added.] Remember a controller’s primary responsibility is to sequence and separate traffic, not you from cumulogranite. Issuing vectors off of a pilot-nav SID is changing the procedure.

In the U.S., controllers keep pilots away from obstacles using minimum vectoring altitudes (MVA, used mainly by approach controls) or minimum instrument altitudes (MIA, used by centers). Except for a Diverse Vector Area (DVA), ATC does not have responsibility for obstacle clearance below the MVA/MIA. Even above the MVA an aircraft must be in radar contact then assigned a vector or direct routing for ATC to assume obstacle-clearance responsibility. Criteria for an MVA are very similar to an MSA: 1000 feet AGL will be the lowest MVA and often they are higher.

The last-minute change in the example often happens when a vector SID is an option for ATC. This is the case in KSTS, where the CHRLY4 departure (named after the Charlie Brown creator, who is also the airport’s namesake) allows an assigned heading between 130 and 220 off Runway 20.

While the change might not be a big deal for a controller, it can be for a pilot. The FREES8 departure only requires a standard climb gradient of 200 feet per nautical mile, while the CHRLY4 has a minimum climb rate of 408 feet per nautical mile until 5600 feet. That could be a lot for a heavily loaded 172 on a warm day or easily surpass the single-engine climb rate of a twin.

Other cases where towers issue headings without an associated SID is when a vector SID formally existed but has been decommissioned or departure control assigns a heading for spacing. In the first case, controllers are used to providing vectors, so they don’t think anything about continuing to doing so. The second case is for traffic separation and frequently happens when departing uncontrolled fields and receiving a clearance of “enter controlled airspace heading…”

Pilots have a couple of options given a last minute heading on take-off. One is to say unable: It helps to explain why. Another option is to eyeball the vector SID and see if compliance with the procedure would be an issue. Also, taking a look at the ODP can help. Many ODPs only require climbing to a certain altitude before turning. For example, when departing Miami Executive (KTMB) Runway 9L, the ODP only requires flying to 800 feet before turning right. This is not the case for KSTS. But, there is one more option.

Diverse Vector Area

The FAA recognized the gap between controller’s priorities and pilot expectations when creating diverse vector areas. Pilots expect ATC assigned headings to keep them clear of obstacles. A DVA does this. As the AIM explains:

ATC may assume responsibility for obstacle clearance by vectoring the aircraft prior to reaching the minimum vectoring altitude by using a Diverse Vector Area (DVA). (5-2-8.c.2)

JO 7110.65 complements, stating “At those locations where diverse vector areas (DVA) have been established, terminal radar facilities may vector aircraft below the MVA/MIA.” If Santa Rosa had a DVA, that could have been used when given a vector off of the FREES8.

DVA’s are rare birds, like a Golden-Winged Warbler. If they do exist for an airport, they are found in the IFR Takeoff Minimums, Departure Procedures, and Diverse Vector Area (Radar Vectors) section of AIS charts and on the back of the airport diagram chart for Jeppessens.

If Santa Rosa had a DVA though, it would probably look a lot like the CHRLY4 departure. This is Oakland, California’s DVA:

Rwy 10L, headings as assigned by ATC; requires minimum climb of 340′ per NM to 2300. Rwy 10R, headings as assigned by ATC; requires minimum climb of 330′ per NM to 2300. Rwys 12, 15, headings as assigned by ATC. Rwys 28L, 28R, 30, headings as assigned by ATC; requires minimum climb of 240′ per NM to 2400. Rwy 33, headings as assigned by ATC; requires minimum climb of 210′ per NM to 2400.

The climb gradients are similar to those found in vector SIDs for the airport. But, a DVA can be used in conjunction with pilot-nav SIDs. Therefore, at airports where DVA’s exist and performance could be a problem, a pilot has to check both departure and DVA performance.

Gumming Up the Works

Managing air traffic requires a complicated system that works with little wiggle room. Gumming up a controller’s plans by not taking a heading doesn’t make friends. But, sometimes being PIC requires holding one’s ground.

If there’s no ODP for an airport, once reaching 400 feet off the departure end a turn can be made in any direction. The only requirement is the standard (200 feet per nautical mile) climb gradient.

Even with an ODP, weather is often good enough to see and avoid obstacles. TERPS says a “ceiling value may also be required to see and avoid an obstacle.” Note the take-off mins for KSTS Runway 2: “std. with a min. climb of 319′ per NM to 2400, or 1200-2 for climb in visual conditions.”

Visually avoiding obstacles only applies within three miles of the runway. That explains the difference between the 1200-foot ceiling and the top of the non-standard climb gradient of 2400 feet. If the top of the climb gradient and the ceiling were the same it would indicate that any obstacles were all within three miles of the end of the runway.

For obstacles more than three miles from the runway either comply with the ODP climb gradient or make a Visual Climb Over Airport (VCOA) which only requires the standard climb gradient. A VCOA is found in the take-off minimums section of AIS charts. Often VCOA are like they sound, circling the airport until reaching a certain altitude. The VCOA for KSTS is to “climb in visual conditions to cross STS VOR/DME [located on the field] southwest bound at or above 1200.” A VCOA doesn’t help with headings on take-off, ATC cannot assign one, and it gobbles up airspace.

Blindly following an ATC heading on departure can be a setup for catastrophe. ATC’s priority is separating and sequencing traffic, not keeping you away from obstacles. Only once radar contact is established and a heading issued will they take responsibility. Until then, it’s important to know what you’re signing up for and what you can do.

Check climb rates for ODPs, SIDs, and DVA. If performance requirements are too high, take note and don’t let ATC’s authoritarian air dissuade you from exercising your responsibility. If you need to stay on the published procedures, you can always say, “Unable headings, I need to stay on the FREES8 for operational necessity.”

At his day job flying an airliner, Jordan Miller is diligent to avoid CFIT and make his mother proud.