A beautiful VFR day in south Florida was coming to a close. The shadows of beach-front hotels were stretching across the sand 3500 feet below. For my first cross country after getting my private, my wife and I flew VFR from Miami’s Opa Locka airport up to Stuart for some Mexican food—a $100 burrito run, so to speak. We were headed home along the coast.

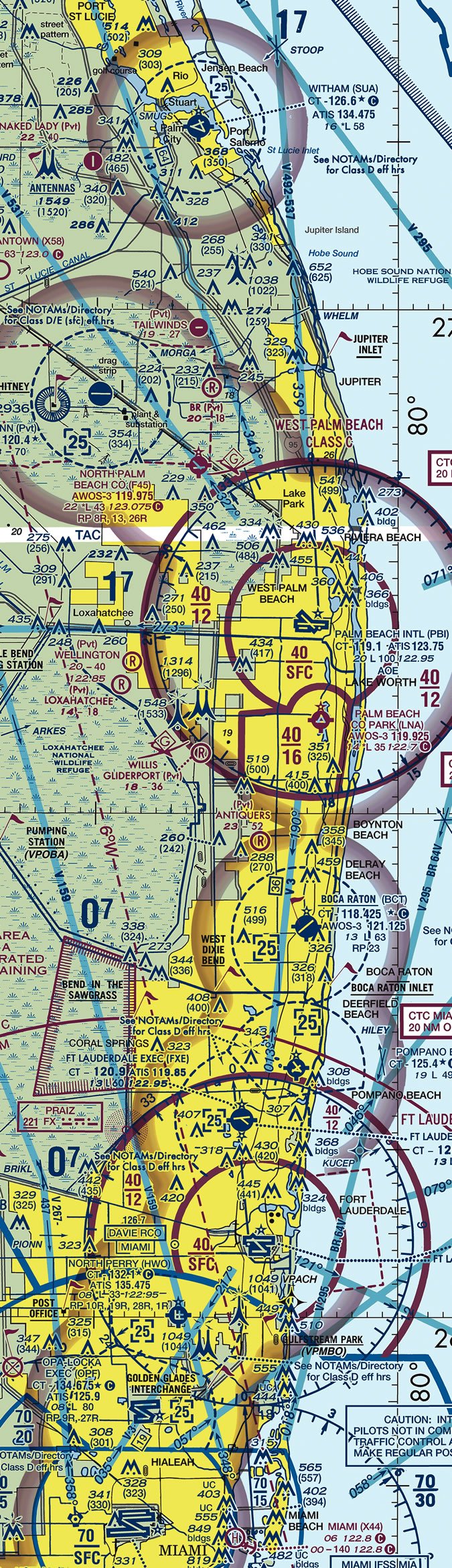

Our return route cut across a couple busy Class C airports—West Palm Beach International and Fort Lauderdale International—so I requested VFR flight following. Being brand new, I figured a few extra sets of professional eyes would help keep me out of trouble.

Boca Raton airport was ahead and to our right. My wife had dozed off after our dinner, but I kept my eyes scanning, watching for traffic and enjoying the colorful sunset.

Then came the traffic call from Palm Beach Approach. “Cessna 55182, traffic, two o’clock, three miles, IFR Beechjet 400, departing Boca Raton airport, northeast-bound climbing out of 1000.”

In the contrast between dark ground and blinding sun, I could see the Boca airport, but no hint of the traffic. I was lined up perfectly with the departure path of Boca’s single runway—in hindsight, not the best choice. Again, ATC hit me with a traffic call. Two miles now, climbing through our altitude. He also told the Beechjet to turn 20 degrees right for traffic, and gave him my position.

The Beechjet reported us in sight. Just then, I caught the gleam of sunlight on metal. The jet shot right to left across my windscreen, same altitude. He was maybe a couple hundred yards away. My instincts pushed the yoke forward to build that extra bit of space. “Traffic in sight,” I managed as the sudden negative G tried to reintroduce me to the Mexican extravaganza in my stomach.

The Beechcraft sailed past and I climbed back up to 3500 feet. Beside me, my wife stirred. “What’s wrong?” she asked with a stretch. I patted her leg and said, “Nothing. Don’t worry about it.”

Later when I became an air traffic controller, I kept that incident in the back of my mind. We’d requested flight following. ATC had their eyes on us. That jet was IFR, so ATC was responsible for their separation. How close could the controller have let us get?

Who’s Responsible?

Who’s responsible for separating IFR aircraft and VFR aircraft from each other? If you answered, “ATC,” you’d be right. If you answered, “pilot,” you’d be right. Both parties share the responsibility.

Kicking off with ATC, the first sentence of the first regulation in the air traffic control rulebook is, “The primary purpose of the ATC system is to prevent a collision between aircraft operating in the system and to organize and expedite the flow of traffic…” This paragraph of FAA Order 7110.65 section 2-1-1 doesn’t mince words. Keep planes from colliding, and keep them moving. The statement doesn’t differentiate between IFR or VFR aircraft.

Moving over to pilots, 14 CFR 91.113 on right-of-way rules states: “When weather conditions permit, regardless of whether an operation is conducted under instrument flight rules or visual flight rules, vigilance shall be maintained by each person operating an aircraft so as to see and avoid other aircraft.” This puts the pressure on the pilot to avoid hitting other planes, with an implied emphasis on VFR pilots, since they’re supposed to be flying in visual conditions.

So, the regulations say both controllers and pilots are obligated to prevent collisions. This is reflected in rules such as the 7110.65’s section 3-1-1: “When operating in accordance with CFRs, it is the responsibility of the pilot to avoid collision with other aircraft. However, due to the limited space around terminal locations, traffic information can aid pilots in avoiding collision between aircraft operating within Class B, Class C, or Class D surface areas and the terminal radar service areas, and transiting aircraft operating in proximity to terminal locations.”

Identify Yourself

You don’t need a genius IQ to figure out the best way to keep two aircraft from colliding is to ensure space between them. The “see and avoid” regulations above and basic self-preservation instincts drive pilots to keep their distance from other airplanes. The controller side of the spacing equation is a bit more complex.

The first thing a controller needs to do before separating aircraft is identify which aircraft is which. Order 7110.65 3-1-1 directs controllers to “Provide airport traffic control service based only upon observed or known traffic.” The FAA defines “known traffic” as “aircraft whose altitude, position, and intentions are known to ATC.” Only after assigning a squawk, requesting an ident, establishing visual contact from a control tower or otherwise confirming an aircraft’s identity and location, is the aircraft considered “known” and we can provide separation services.

When I requested flight following from Stuart Tower, I told them my call sign, type, requested altitude, and my intention to fly back to Opa Locka. They gave me a squawk, and when I departed Stuart, Palm Beach Approach radar-identified me. I was therefore known VFR flight-following traffic. When the jet departed Boca Raton, he became known IFR traffic to the Palm Beach controller.

For just IFR-to-IFR aircraft separation, it’s pretty cut and dry: a minimum of least three miles horizontally or a thousand feet vertically. There is some wiggle room dependent upon wake turbulence restrictions, the aircraft’s distance from the radar site, current altitude, the use of visual separation, or the type of facility working the aircraft, as we discussed last month. Aside from visual separation, generally speaking those changes increase the basic separation requirements as defined in the 7110.65.

It’s the spacing requirements between identified IFR and identified VFR aircraft that gets a bit fuzzier. The only specifics depend on the kind of airspace the aircraft happen to be occupying. Class A is all IFR traffic and Class G is completely uncontrolled, so here we’re focusing on Class B, C, D, and E.

Running With the Big Dogs

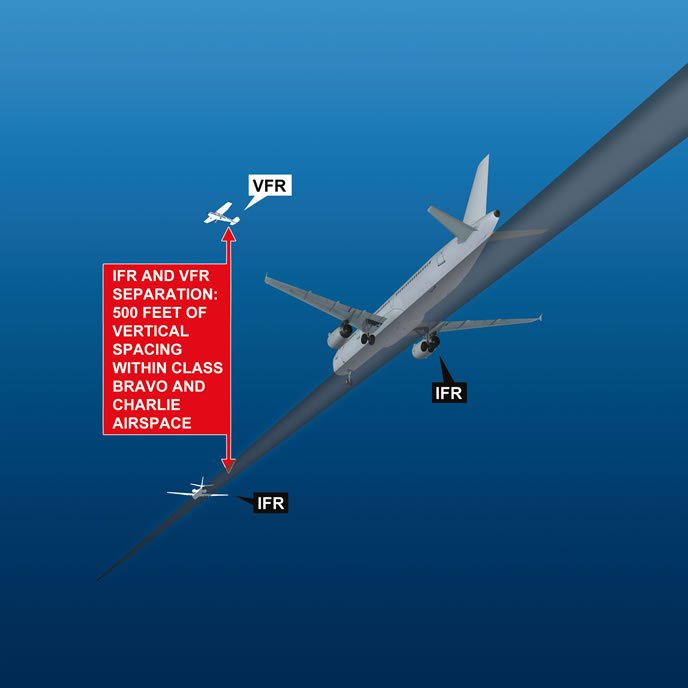

Within the Class B and C airspace around larger airports, sections 7-8-3 and 7-9-4 of FAA Order 7110.65 instruct controllers to “Separate VFR aircraft from IFR aircraft by any one of the following: a. Visual separation…; b. 500 feet vertical separation; c. Target resolution.” The first two are pretty self-explanatory. Does either aircraft have the other in sight? Yes? Don’t hit him. Vertical separation? If the VFR plane is restricted 500 feet above or below the IFR plane, then they’ll cruise on by without worry. In short, “See ‘em or stack ‘em.”

What’s that target resolution thing? The 7110.65 definition in 5-5-3 (a) is: “A process to ensure that correlated radar targets or digitized targets do not touch.” Calling it a “process” makes it sound so very complicated. It’s not.

Perhaps you’ve seen an ATC radar scope on TV or even in person. Hollywood’s depicted them a thousand different ways, very few of them accurate, but they’ll usually get one aspect right: real scopes feature bright aircraft targets on a dark background.

The target resolution “process” is pure simplicity: keep those targets from touching each other. That’s not rocket science; it’s common sense. Does ATC have two aircraft at the same altitude? Just issue them headings to ensure their targets don’t merge. Section 5-5-3 (b) of our rulebook also requires that “Mandatory traffic advisories and safety alerts must be issued when this procedure is used.” If a controller’s going to be running his airplanes that tight, he’s required to tell the pilots about each other.

There are some stipulations regarding target resolution. Wake turbulence rules still apply. If ATC is vectoring a smaller VFR plane behind a larger one—as opposed to the VFR plane visually following the other traffic—then ATC must sequence him a certain number of miles in trail to account for wake. Also, in Class B, VFR aircraft must be separated by 1-1/2 miles from aircraft with a max takeoff weight of over 19,000 pounds.

Those stipulations reflect that VFR aircraft aren’t usually very large or fast. While I’ve occasionally worked VFR Boeing 757s and F/A-18s, most VFR traffic is a light piston single with the occasional twin. Meanwhile, the higher volume of IFR traffic into bigger airports is largely comprised of heavier turbine fast-movers.

Morally Obliged

Had my Cessna been inside Palm Beach or Fort Lauderdal’s Class C airspace when the jet flew past us, ATC would have had to use one of those three options. But, we were in the Class E between the terminals, just above Boca’s Class D. Venturing outside the highly structured confines of Class B or C peels away ATC’s specific IFR-VFR restrictions. There is no 500-foot vertical or 1-1/2-mile-horizontal spacing requirement between smaller and bigger planes in Class D or E airspace.

What’s left? Remember our basic job description in 7110.65 2-1-1? “The primary purpose of the ATC system is to prevent a collision between aircraft…” Controllers have a legal obligation to prevent aircraft collisions and a moral obligation to provide safe passage for the people inside those planes.

Combine that mandate with regulations such as 2-1-6: “Issue a safety alert to an aircraft if you are aware the aircraft is in a position/altitude that, in your judgment, places it in unsafe proximity to terrain, obstructions, or other aircraft.” Now ATC’s requirements are twofold: take positive action and provide traffic information when necessary.

If a controller allows two aircraft to collide under his watch, the investigators will be slinging the questions at him. Did he offer a traffic alert? A suggested heading? An altitude restriction? Use any other vectoring option at his disposal? No? It’s likely at least some responsibility will rest heavily on his shoulders. It’s in everyone’s best interest for controllers to employ one or even all of the tools I just mentioned to keep VFR and IFR airplanes apart.

In my Boca Beechjet situation, the controller used two of his options: traffic calls to both me and the jet, followed by an adjusted heading for the Beechjet. When I got the jet in sight, I had time to maneuver myself away from it. It was closer than I would have liked, sure, but the job got done. It just shows that legal doesn’t always mean comfortable.

Accounting for that legal-versus-comfortable disparity, many controllers—myself included—will still employ altitude restrictions or vectors to VFR aircraft outside of Class B and C. Examples of this? Restricting a VFR helicopter at 1500 feet or below when they’re passing an IFR Cessna in a practice VOR hold at 2000 feet. Another would be assigning a hard altitude of 3500 feet to a VFR Cherokee on an airway sandwiched between an IFR Beechcraft Baron overtaking him at 3000 and an opposite direction IFR Cirrus at 4000.

Now we’re back to the original question: how much space does ATC need between IFR and VFR traffic? The answer? Whatever is necessary to ensure safety.

That’s not a side-step answer. It just shows the system’s flexibility. Separation may come through ATC vectors and altitude restrictions, or via traffic advisories enabling the pilots to create their own spacing. None of that would happen, though, without plain ol’ vigilance and proactive action on the part of both pilots and controllers. Keep your eyes open.

Tarrance Kramer keeps his IFR and VFR planes stacked like sweet potato pancakes while working traffic somewhere in the southern U.S.