One element of IFR flying that’s universally disliked among pilots is the circling approach. The prospect of flying visually in marginal weather conditions at low altitude while configuring the aircraft for landing and, oh yeah, not straying beyond sight distance of the airport, understandably strikes fear into the hearts of many pilots, and with good reason. Circling approaches are serious business and offer plenty of opportunities to get in trouble.

Circling can certainly be a valuable tool to have in the IFR pilot’s flight bag when the weather mandates its use. For instance, you might encounter a situation in which the runway with all of the approaches is closed, but there is another visual-only runway still available. Thinking slightly outside the box, you can still fly an approach to the closed runway, then break off and circle to the open runway.

But, workload management challenges aside, circling is really only a means to an end. You still need to get down to the runway, and that’s where things can really get tricky. Let’s take a look at recent changes in circling standards, what sort of obstacle environment can exist in the circling area, and what to look out for when considering a circle-to-land.

How Much Elbow Room?

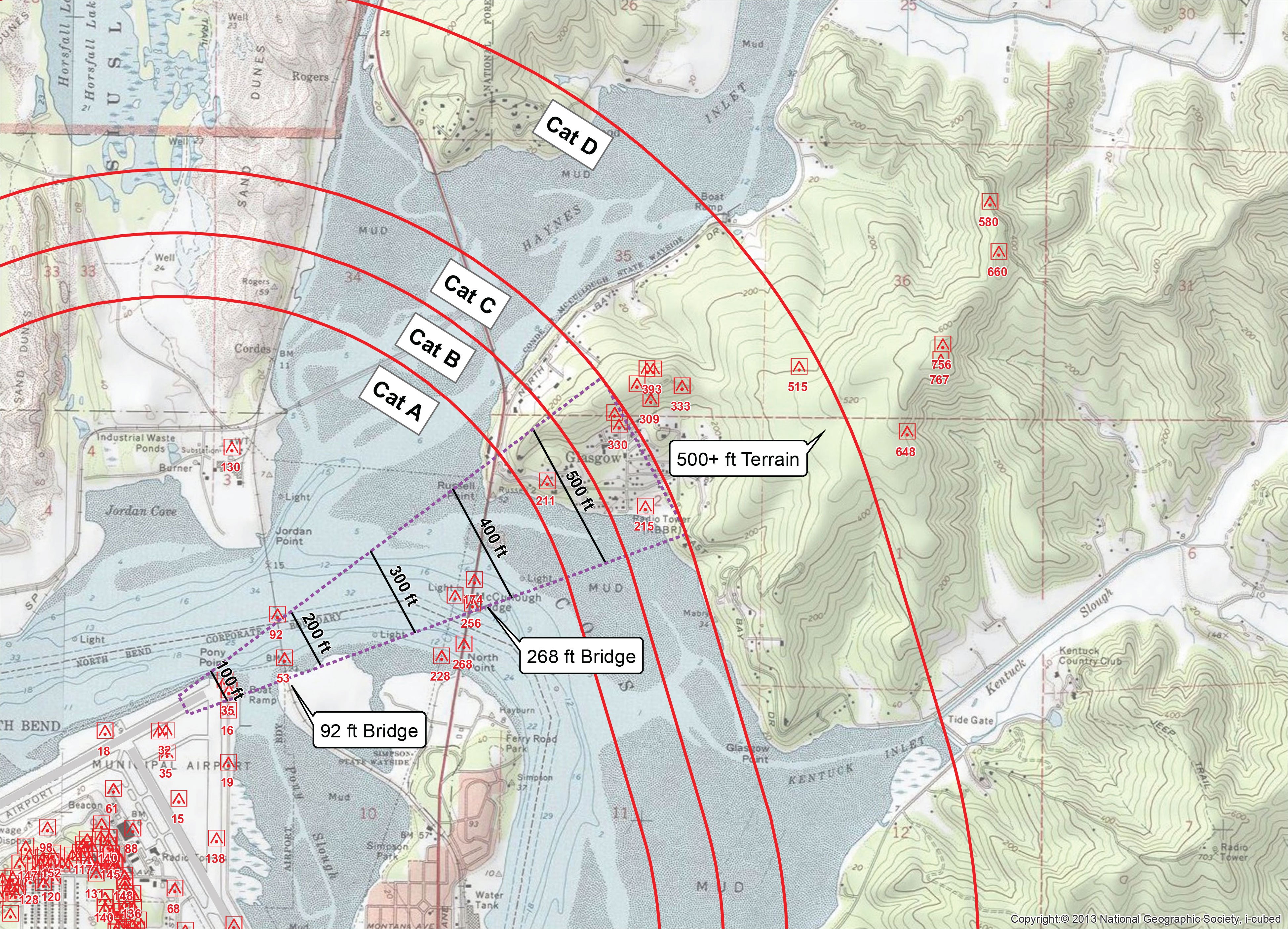

Hopefully you’ve heard about the recent changes to the circling radii evaluated during procedure development, since approach charts using the new distances, and featuring the icon have started to show up in the last few approach chart publication cycles. The changes expand the circling radii for all aircraft in the hopes that a larger protected area will make it easier to fly stabilized approaches following a circle-to-land.

Historically, many accidents related to circling maneuvers have resulted from pilots staying too close to the runway and then overshooting the turn to final, or ending up high and overshooting the runway. Additionally, the old circling radii standards were based only on approach category, and therefore, indicated airspeed. However, this did not account for increases in true airspeed at higher elevation airports resulting in corresponding increases in required turn radius. The new standards address both of these concerns.

The revised standards will result in an increase to the circling minimums on many approaches, but will give you more room to maneuver. However, it will take a while for the FAA to update every procedure. For the foreseeable future, if you’re considering circling, pay attention to whether the procedure has the icon or not, so you will know which set of standards your obstacle protection is based on.

In determining circling minimums, the circling area for each approach category is evaluated independently, and the highest obstacles are identified. The circling MDA is determined to be the highest of 300 feet above that obstacle, the straight-in non-precision minimums for the procedure, or the lowest authorized minimum (450 feet above the airport for category B and C aircraft).

From the cockpit, this means that as long as you stay within the circling area, you will have no less than 300 feet between you and the nearest obstacle. Also, if you notice a circling area restriction in the procedure notes, be sure to pay attention and comply with it, since it’s there for a good reason. A restricted circling area (“Circling NA east of Rwy 18-36”) exists because an obstacle in the described area would have led to an unnecessarily large increase in the circling minimums. Take their word and don’t go looking for it.

It Doesn’t Look That Bad

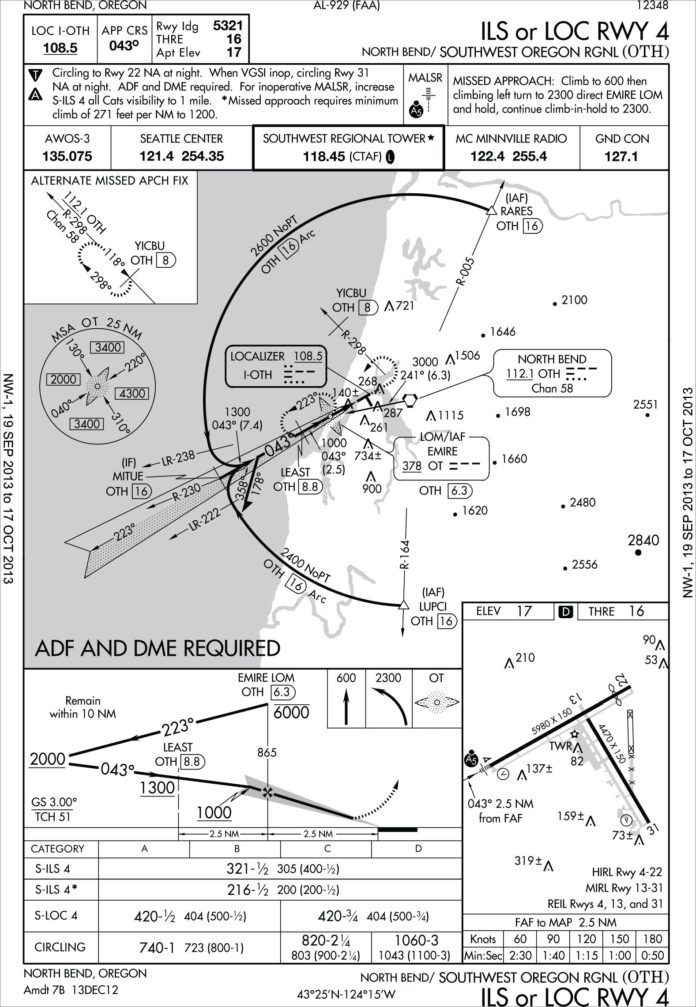

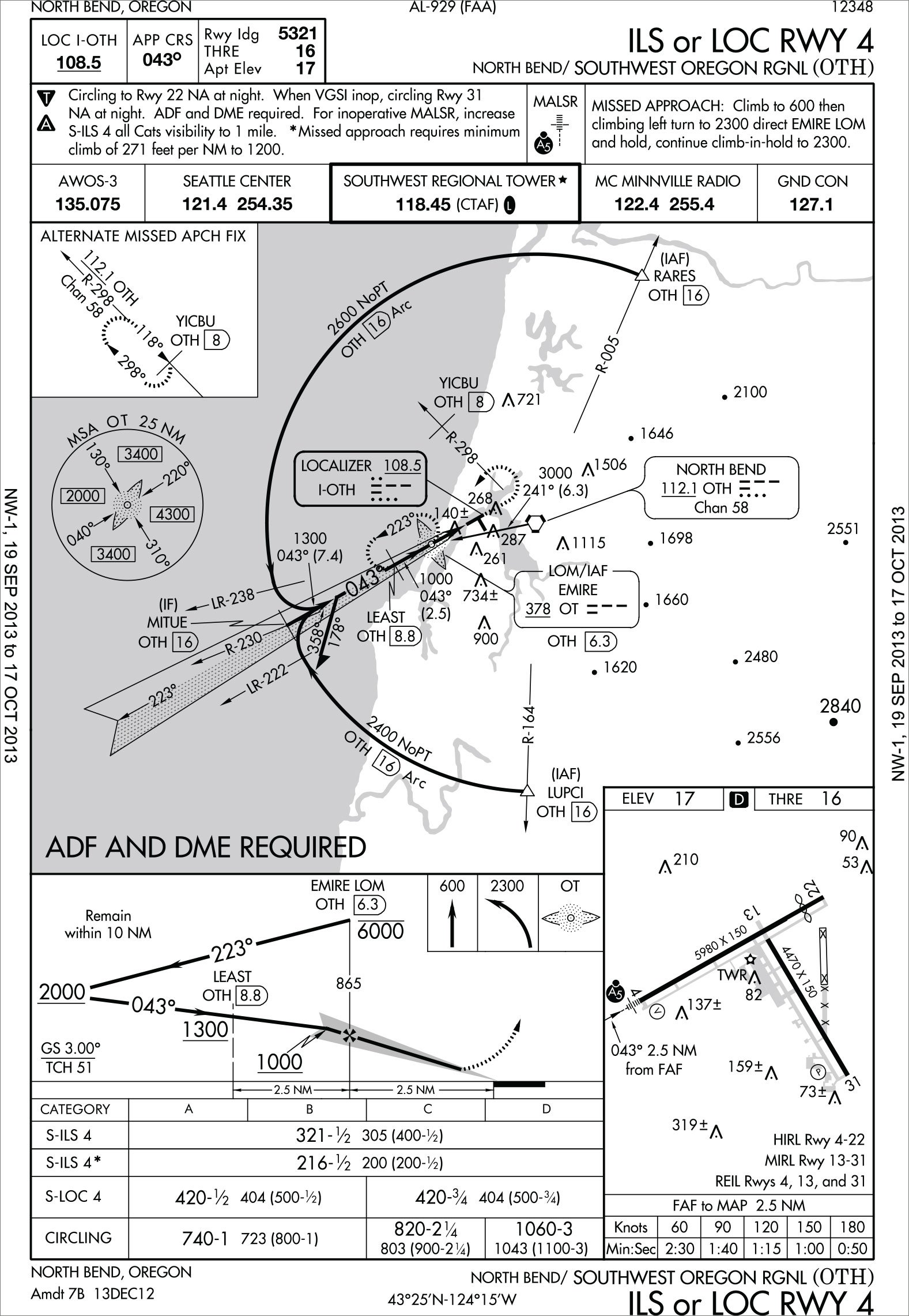

The textbook example of a scenario where you might consider a circle-to-land is when an airport has procedures published for only one end of the runway, but the wind favors a landing in the opposite direction. That is a scenario often found at North Bend, Oregon (OTH). It has several approaches to Runway 4, including ILS and GPS procedures, but no approaches to Runway 22, which the wind frequently favors. A quick glance at the procedure doesn’t reveal any obvious circling challenges, but reading between the lines turns up a few flags.

The first, call it a yellow flag, is that there no approaches to Runway 22. These days, you can get a GPS procedure just about anywhere, so if a runway, particularly at an airport with airline service, doesn’t have one, there’s probably a good reason. Although there could be other plausible explanations, chances are it’s because the obstacle environment wouldn’t allow a reasonable straight-in procedure.

The next red flag is the procedure note that “Circling to Rwy 22 NA at night.” This restriction exists because the visual area to Runway 22 is penetrated by unlit obstacles. Similar to those found on straight-in procedures, each runway end that is available for circling has an imaginary surface that is evaluated for obstacles. This surface extends 10,000 feet (1.65 nm) beyond the runway end at a 20:1 slope. There is no penalty if the surface is penetrated by a lit obstacle, but if it is penetrated by an unlit obstacle, as in this case, it is not authorized for circling at night, unless the runway has a VGSI.

The fact that Runway 22 doesn’t have a VGSI either is further cause for concern. Granted, the airport management might just be cheap, but it’s likely that the obstacle clearance requirements of a VGSI couldn’t be met. Two more warning signs are the fact that there is a displaced threshold for Runway 22 and that the missed approach for Runway 4 requires a nonstandard climb gradient. All of these indicate that there are quite a few things to hit off of the approach end of Runway 22.

Stabilized Circling

Since it’s fundamentally a visual maneuver, once you descend below the circling MDA, it’s solely up to you to visually avoid hitting whatever happens to be down there. The only guarantee is that as long as long you’re at or above MDA (and within the circling area), you won’t hit anything. From a workload management perspective, you’ll already have your hands plenty full, so remaining at the MDA for as long as possible means one less thing to worry about.

In order to descend below the MDA, 14 CFR 91.175(c)(1) requires that the pilot must ensure “The aircraft is continuously in a position from which a descent to a landing on the intended runway can be made at a normal rate of descent using normal maneuvers.” This is essentially the stabilized approach concept, and circling approaches don’t get a free pass. For air carriers, the stabilized approach criteria usually look something like being configured, on course, on speed, on glidepath and with a descent rate less than 1,000 fpm, by 1000 feet AGL, possibly sometimes as low as by 500 AGL.

Many pilots think of a circle-to-land maneuver as a traffic pattern flown unusually low to the ground. The problem with this line of thinking is that since you are unusually close to the ground, in order to achieve the sight picture that you’re accustomed to for a traffic pattern, you would need to fly unusually close to the runway. Illusions caused by low visibility also contribute to this tendency. This is definitely not the ideal beginning for a properly stabilized approach.

Instead of considering a circling maneuver to be a variation on a traffic pattern, think of it as a different approach requiring its own pre-determined plan from entry to landing. One strategy to ensure consistent spacing from the runway for both entry and determining when to start your base turn is to use time (20 seconds tends to work regardless of aircraft speed). If your landing runway has a VGSI, be sure to stay at or above the glidepath, since that is one way to ensure obstacle clearance. You can also use the tips in

“Simplified Circling” by Dog Brenneman, in the October, 2013 IFR.

When possible, plan to roll out on final no lower than 500 feet AGL, which on a typical 3 degree glidepath occurs at about 1.5 nm. The astute reader might notice that’s the outer limit of the circling area for category B using the old circling radii. Keep in mind that just because you’re flying a category B aircraft doesn’t mean you must circle at the category B MDA. Want a little more wiggle room to make a stabilized approach? Use the category C or D MDA instead.

Legal Doesn’t Mean Safe

Circling visibility minimums are usually a function of the height above airport of the circling MDA, with minimums as low as one statute mile for categories A and B aircraft, one and a half for category C and two for category D. If operating in visibility this low, there is essentially no way that aircraft below category D could be stabilized at 500 feet on a 1.5 n.m. final and not lose sight of the runway. Although I’m not a proponent of personal minimums in the conventional sense, I think there’s a valid safety concern for not executing a circling maneuver with less than two statute miles visibility.

If you’re flying a circling maneuver at 120 knots, you’re traveling at two nautical miles per minute. In one statute mile visibility at that speed, you have about 26 seconds to notice and react to an obstacle. The truth is that the obstacles depicted on approach plates are only a tiny fraction of what’s really out there, so we’re completely reliant on keeping our eyes open.

As a point of reference, many airlines do not permit a circle to land in less than VMC. We could when I flew freight, and I flew a handful of circling approaches at night and near minimums and can say that it’s just not worth it. When the weather is low, it might be a better and safer plan to just land with a tailwind. Otherwise, if a stabilized circling maneuver seems doubtful, use your alternate.

Lee Smith, ATP/CFII, is an aviation consultant, flight instructor and charter pilot in Northern Virginia.