A tiny aircraft, too small to carry a person, flashes past your left wing. You never saw it; neither did ATC. You just had a near miss with a drone.

There are large, heavy commercial and military drones capable of flying in the flight levels. Then, there are little drones that range from toys up to Amazon’s proposed single-package delivery device. While similar, each presents different challenges.

Small drones are difficult to see, mostly invisible to radar, unpredictable and often controlled by those who don’t understand the dangers. It’s a formula for a midair collision if we let it be.

Wanting unrestricted small drones, politicos and executives who care more about corporate profit than safety are pressing the FAA. But, what’s the real risk? I’ve even hit birds that weigh more than the drone 2 kg limit. Some estimates say there are up to 700,000 small drones, and we’re not getting knocked out of the sky just yet. The Academy of Model Aeronautics established common-sense rules to regulate itself and those are largely adopted by the FAA. For example, the AMA admonishes flight above 400 feet AGL and within the vicinity of an airport. When was the last time you flew below 400 feet away from an airport?

That said, there is some risk. Numbers are increasing. As technology improves, drones’ capabilities and potential for interference will increase. Operating envelopes should be electronically enforced to keep them away from airports and below 400 feet. (Some responsible manufacturers already—optionally—do this.)

Large-drone operators have descended drones through flight levels without clearance, flown out of assigned airspace and even plummeted from FL210 to 16,600 feet before regaining control.

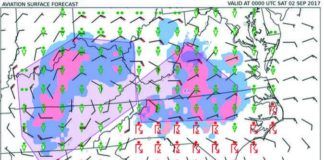

Coordination with ATC is problematic. Big drones get VFR and IFR clearances, but operators sometimes violate them, file incorrectly or fail to file altogether. Communications are uncertain—the controller must phone the operator using phone numbers that don’t always work, can’t be found or were never filed. There’s good logic to require larger drones to have ADS-B Out to find and prosecute the scofflaw operators.

In the early 1960s, the Federal Communications Commission opened a small block of frequencies for public use without a license test. “Citizen’s Band” quickly went viral with millions of users who knew nothing of good radio procedure, didn’t bother with the requisite licensing and often flouted technical restrictions.

That comparison is on-point. Small drone operators are unlicensed. Inherently anonymous operators can’t be regulated; violators can’t be caught. Even commercial operators are often ignorant of the requirements or don’t follow them.

Yes, the risk today is small, even infinitesimal. But the numbers are changing. We can’t rely forever on a big sky to keep us safe. I dread the day when there’s a midair with a UAS, or a near-miss with an airliner that makes the news. Must regulations be written in blood—just like you can’t get a traffic light at a busy intersection until somebody nails a soccer-mom’s minivan full of kids?

The FAA must get ahead of all this. It must move quickly and decisively toward realistic and enforceable restrictions. Political pressure is the only way to make this happen. Hammer them through your congress critters. 10-4?