Some people say that it doesn’t matter where you practice IFR because all procedures use the same cookbook. An ILS is an ILS whether it ambles downward over the flatlands of Kansas or threads a nervous CDI needle between Colorado mountains. It doesn’t matter whether you’ve done the approach a hundred times or this is the first, you’re still flying the approach.

They’re wrong. Fear of course-deviation CFIT heightens the senses and sows self-doubt. Familiar procedures breed a creeping complacency. At least they do until those really low days when you realize you’ll be in this cloud down to cell-tower level.

That’s why when tasked with a final stage check for a pilot in Wisconsin, I had him fly it in Washington state—for his checkride in California.

Let me explain.

This student and his instructor put the Zoom into flight training. They had done an entire instrument training course from their respective basements. The student had a non-certified home simulator with instruments on one (touch sensitive) screen and an outside view on the other. The instructor in a different basement could see both of those screens, plus the student’s iPad. The student was visible via a webcam. The instructor could also control the student’s sim remotely. Once they reached a point in the syllabus where they would fly in the system, they flew with live ATC on PilotEdge. This even allowed something you could never do in real-world training: solo IFR crosscountries.

Was this effort loggable flight time towards a real rating? Heck no. Did it craft a pilot who would pass a virtual IFR checkride administered by the famous Doug Stewart? It did. The training product that came from the captured video can be seen at PilotWorkshops.com. And you can also fly the final stage check right now.

A Familiar Start

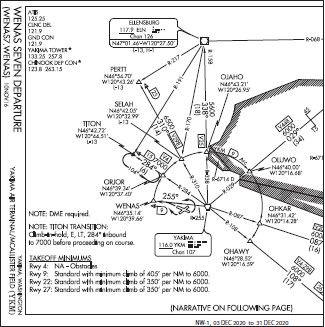

Regulars to this sim challenge will recognize the departure point: Yakima, WA, KYKM, for the WENAS SEVEN departure. (See “Wenas Returns,” IFR February 2019.) Your clearance is WENAS 7 OJAHO ELN KELN at 6000. If you can fly this with an IFR GPS, do so because this stage check was designed with that in mind. However, assume (as I told this student) that there’s a NOTAM potential GPS outages. Plan accordingly. Then, if your sim has DME, disable it or just turn it off. You probably don’t have it in a real airplane with GPS anyway.

If possible, set the weather to real-world so you can get weather on your tablet. If not, set strong winds aloft and reasonable ones at the surface from the north or south as you wish. Either work for today’s flight. Feel free to set minimums for ceilings or change the view so you can’t see outside until the examiner says so. Or wear a view-limiting device for that “full checkride immersion.”

Start on the ramp at KYKM. Tune all frequencies as you would in the real world. Depart on the WENAS SEVEN. About ORJOR you get a revised clearance: “After SELAH, join V468 ELN.” Halfway to up V468, disable your GPS (ideally by failing GPS position in the sim itself). Also remove the “ownship” position on your tablet. Notify ATC you’ve got no GPS and answer their question about intentions by telling them what approach you want at KELN. If you have an autopilot, use it for this entire section, including

the approach.

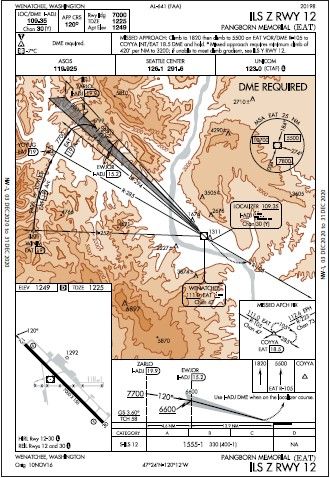

Fly the approach of your choosing to a published missed. Climb in the hold to 9000 as you copy your clearance to Wenatchee: ELN V25 EAT KEAT. After reaching 9000 and crossing ELN, restore your GPS to all devices but disable the autopilot for the rest of the flight. Proceed on course while you climb and maintain 11,000. Upon reaching 11,000 proceed direct WINIM for either the ILS Y or Z at KEAT. (If you have no GPS cross EAT and fly EAT R-257 to WINIM at 11,000 even though that’s not a real published route.) Cross WINIM at 11,000 and fly the approach

to a straight-in landing, looking up at minimums.

Taxi to the ramp.

- This is where GPS can be more difficult than going old school. Most GPS units load an arc as a single leg from start to exit. That means SELAH usually isn’t depicted. Try to edit the arc and add SELAH? You can’t because it’s an active leg. Reload the entire departure? You could, but you’d lose guidance while doing it. The easiest way is to use a VOR or second GPS to identify SELAH and get going on V468, and then reprogram the GPS.

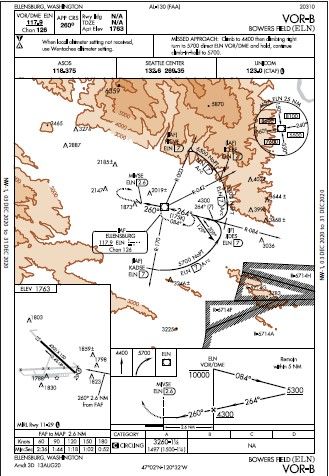

- The VOR-A requires DME, but GPS would substitute—when it is working. So, without real DME, all you can fly is the VOR-B via the ELN IAP—which is an approach loaded with traps. You started at 6000, which at least means you don’t have much altitude to lose in the procedure turn. That’s good, because it’s “remain within 5 NM.” Did you? Once inbound you have 1000 feet to lose by the FAF and another 1040 to lose in 2.6 miles, less if you want to land Runway 29 without much circling. If you had an extra 2000 feet to lose at the IAF, it would have been … more challenging. There’s also a four-degree course change passing the FAF which can be easy to miss. And the hold at the missed is lefthanded, not right. This is a poster-child approach for “brief it carefully.”

- The VOR-A requires DME, but in our virtual checkride and the real-world ATC could help. DME is needed for the stepdown at DIBPE, which ATC could call for you. The controller even offered on our stage check flight, but the student didn’t take the bait and flew the VOR-B anyway. No matter what approach you fly, don’t forget to start your timer. There’s no other way to identify the MAP.

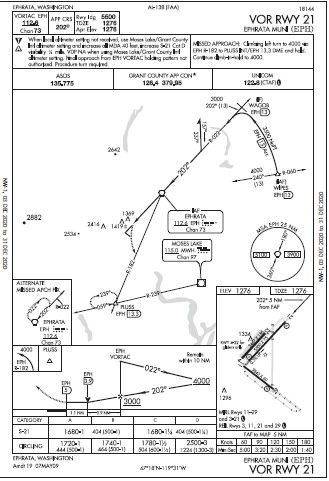

- The Z approach is certainly what you want when conditions are low with a DA of only 330-feet AGL rather than 1208 AGL. The difference is the missed where you need 420 feet per mile and get a different missed-approach holding point, MAHP. Either way, it’s a 3.6-degree glideslope. If you didn’t catch that in the briefing, you’ll be chasing it the whole way down—and it’s a long way down from intercept to DA. In fact, if you don’t plan well, you’ll chase altitudes all the way from crossing WINIM at 11,000. Also if the GS is INOP it’s a no-go. There is no localizer-only version of this approach due to terrain.

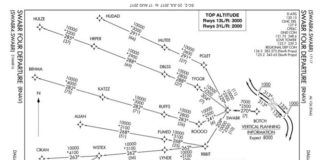

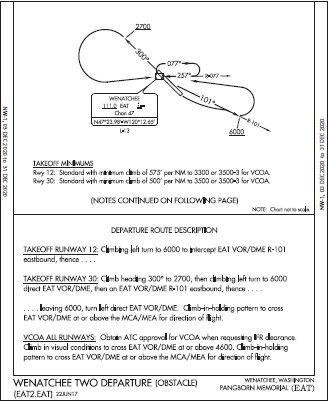

- The OFARO 2 makes it easy with RNAV because there’s a valley you get to fly down to fair terrain. But did you see the climb gradient of 500-550 feet per mile? The Wenatchee 2 is more complex and requires a close read. First is a climb gradient that’s as bad or worse. This makes the VCOA your only choice if you’re a slow climber. But here’s a question: If you depart Runway 30 on the Wenatchee 2 and reach 4600 by the time you get back to the VOR, can you just climb in the holding pattern right then rather than do the trip down R-101 and back? It’s safe, but would it comply with the clearance you got? As always, if in doubt, ask. But since you’re climbing to 7000, would you gain much?

- No snarky answer here. We’re just curious if you ripped a virtual wing off the virtual airplane.

- There are RNAV approaches to Runways 3 and 21—but neither one has circling minimums. The FAA is phasing out circling minimums to airports where all the runways are served by straight-in approaches, but this one got the same treatment. Presumably this is because there’s a VOR Runway 21 approach with circling minimums, which means that’s the only approach you can fly. You can do it with an IFR GPS, and circle for Runway 11-29. You can’t just sidestep to Runway 4-22 unless you decided to land your sim deadstick. Per a note in the small airport diagram: gliders only.

Two Down, One to Go

Your final destination is Ephrata, WA (pronounced “Ee-fray-ta”). Choose your preferred departure that gets you heading to KEPH on a reasonable route (the non-RNAV one is more fun). Assume a cleared altitude of 7000.

Partway to KEPH it’s time for unusual attitude recoveries. We asked ATC for a block altitude and permission to maneuver left and right of course, just like a real-world checkride under IFR. Do what’s appropriate for you, but fail your primary attitude display. (No, it’s not required by the ACS anymore, but I think it should be and I’m running this challenge. So you’re recovering partial panel. Deal with it.)

Close your eyes and throw in some wild control inputs for 10 seconds before recovering, or something equally effective. Recover. Now keep the attitude display failed and fly any approach you want at KEPH from an IAF of your choosing using your IFR GPS. There’s only one catch: Runway 3–21 is closed by NOTAM. Do what you must and land.

Now see what the critics say about your dress rehearsal performance.

Questioning Yourself

- Assuming you were flying the arc using GPS on the WENAS 7, how did you identify SELAH?

- Which approach did you fly at KELN? How did that go? How would it have gone if you had to start at 8000? How’d the missed approach work for you?

- Could you have flown a different approach at KELN in the real world without GPS? How? No matter what you flew, how did you identify the MAP?

- Which ILS did you fly KEAT and why? Any issues flying it? What if the glideslope was OTS?

- Which departure did you choose from KEAT and how did you fly it? How might that change if you exercised the VCOA option?

- How’d those unusual attitude recoveries go?

- What approach did you f ly at KEPH and how did you maneuver for landing?