It was late afternoon and time to fly home after a productive business meeting. Before heading to the airport, the pilot called Flight Service.

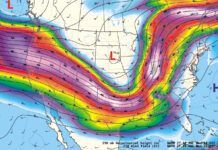

Most of the significant weather was along a cold front just to the north of his east-west proposed route. The briefer mentioned some light snow showers were showing up on radar near the front. There were a few pilot reports of light to moderate icing, but all of them were associated with the weather to the north. The briefer alerted the pilot to an AIRMET for IFR conditions and mountain obscuration along a portion of his proposed route, but as of yet no en route advisories for structural icing had been issued.

With no pilot reports of icing and no official icing forecasts, the pilot must have concluded that there was little or no risk for structural icing. He filed a flight plan, drove to the airport and departed on what turned out to be his last flight.

Accidents Don’t Lie

This pilot’s case of death by icing is far from unique. In a recent study, the NTSB examined all icing accidents from 1982 through 2000. The study determined that 81 percent of all accident pilots received some type of weather briefing prior to the flight. Of those accident pilots who got a briefing, 82 percent received their weather briefing through Flight Service.

This is not to say that Flight Service is directly at fault for any of these accidents. There are a few accident cases where the NWS took some of the heat because they failed to issue an accurate forecast. There are also accidents where the briefer dropped the ball and was partly to blame. However, the overwhelming majority of these accidents were attributed to—you guessed it—pilot error.

While a few of the icing accidents are likely the result of a pilot’s cavalier attitude with respect to icing, many could have been prevented and are an indirect result from several weak links in the system. The accident pilots didn’t understand the severity of the risk or misused the information given in mitigating that risk. Pilots, flight instructors and the FAA all need to look down at their own shoes—we are the stakeholders in aviation safety—but the solution ultimately rests with the pilot.

An Old Paradigm

According to Aeronautical Information Manual (AIM) Chapter 7-1-4a, “Flight Service Stations (AFSS/FSS) are the primary source for obtaining preflight briefings.” This section of the AIM should be relegated to the aviation history books. Reading line after line of text to an inexperienced and perhaps poorly trained pilot is a bad paradigm that just creates a street full of open manholes.

It’s easy for instrument pilots to make errors in judgment when they don’t have all the information. That’s hole number one. Also, instrument pilots have little or no training in applying information. The combination means errors in understanding the guidance given in any briefing and using that information in the context of an IFR flight.

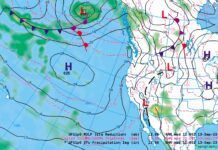

You know the drill. A Flight Service specialist pages through a quick and concise translation of a bunch of coded text on his computer screen and summarizing what he sees on the radar, satellite, surface analysis and prog charts. Without any interruptions, most specialists can deliver the weather portion of a standard briefing in five minutes. Of course, some pilots take the time to ask pertinent questions and get further clarification. Some briefers go the extra mile to help integrate the data for the pilot when the weather is especially challenging. Assuming the pilot pays close attention and the briefer doesn’t leave out any critical details, the pilot will hear the minimum weather data required by the FAA guidelines.

The content of a telephone briefing isn’t bogus and there’s no need to remove the human from the loop. However, a briefing involves the transfer of information. The quality of the briefing largely depends on how well the Flight Service specialist was able to convey information to the pilot.

Back when our “new” Flight Service was big news, we were teased with talk of an online portal so the briefer and pilot could see the same images and text. This would certainly offer an improvement, if it ever comes to pass. But if the data they are sharing is no more than a shoulder-to-shoulder DUATS briefing, then we’re back to a 1980s-style philosophy with a 21st-century twist. Better, but not what the FAA should spend taxpayer money to build.

And what’s completely missing is guidance on using this information. When the specialist says there’s an AIRMET for icing over a four-state area containing the pilot’s entire route of flight, what’s a pilot supposed to do with that information, especially if the pilot isn’t experienced enough to know ice won’t be found everywhere within the AIRMET?

Education is Key

My advice is to expand your briefing beyond a simple phone call. Some internet-savvy pilots use online resources exclusively for their briefings. To some that may seem impetuous, but to place any formal briefing in context, you should always integrate some of what’s available online. When you get that five-minute standard briefing 20 minutes before departure, you’re then listening for recent updates and amendments to the forecast, perhaps getting some clarification and adjusting your plan accordingly.

Unlike our accident pilot, however, you won’t be relying solely on FSS to know where dangerous icing might lie.

But it takes much more than just scouring the internet for data. Pilots often feel that they have no need for additional training in aviation weather; they believe they’ll acquire understanding on their own as they gain more flight experience. That’s a dangerous mindset.

Using new weather products often requires learning new analysis techniques and how to best integrate this guidance with all of the legacy weather products. To their credit, the FAA does describe some of this ancillary weather guidance in Advisory Circular 00-45G (Aviation Weather Services). The weather products discussed in this AC are all freely available online. Before your next IPC, read this AC cover to cover and spend an afternoon next to a computer with your instrument instructor learning how to use these products effectively. If you feel your instrument instructor isn’t up to the challenge, find one who is.

From Data to Decisions

The last step is finding someone who can help you turn weather information into flight strategies. Ideally, our FSS briefers would do this, but that’s never going to happen. You need to learn this skill from a mentor until you are able to do it for yourself. Having the right weather information without knowing how to apply it is like someone handing you a sharp ax, but not giving you any instruction on how to swing it.

A standard briefing from Lockheed Martin Flight Services can be useful when you don’t have immediate access to online weather (rare these days). But when it comes to real flight hazards, such as structural icing, it will never be enough. You can make up the gap. Or you can take what an official briefing offers and hope it’s enough to keep you out of the NTSB reports.

Scott Dennstaedt is an IFR Contributing Editor. His website is avwxworkshops.com.