Unless you’re under age 30 or live in a remote village in Mongolia, you’ve likely heard the 1971 Don McLean song “American Pie,” in which the events on the night of February 2-3, 1959 are recalled. That night, three of America’s top rock musicians died in a tragic aviation accident in Iowa. The accident is ingrained in American culture. I can’t think of a better example of an accident worth researching for lessons to learn.

The Fateful Day

Don McLean said that his song refers to the loss of these musicians and the culture that followed. At the time, McLean was a 13 year-old boy in Westchester County, New York, but the event impressed him deeply: “with every paper that I’d delivered, bad news on the doorstep.”

Years later, he lamented the state of modern culture, with the Beatles symbolized by “the sergeants [who] played a marching tune,” and Janis Joplin as the girl who sang the blues. While McLean is evasive about elements in the song, he describes it as recalling a simpler time.

The subjects of the song were Buddy Holly, The Big Bopper (J.P. Richardson), and Ritchie Valens. The three artists were on the Winter Dance Party tour covering the Midwest.

An unusually strong cold wave was plaguing the region. Morning temperatures ranged down to -10 degrees F across Iowa and struggled to reach highs of 20. Worse, the tour traveled in unheated school buses. Band members were suffering, including drummer Carl Bunch, who had been hospitalized a few days earlier for frostbitten toes.

Facing a seven-hour bus ride to a venue near Fargo, North Dakota, Buddy Holly turned to aviation. He contacted a local charter operator, Dwyer Flying Service, to take them ahead after the evening’s show in Clear Lake.

Charter owner Jerry Dwyer enlisted his 21-year old junior pilot, Roger Peterson to make the flight. Peterson was planning for a career in flying, and had a modest 711 hours total time, with 52 hours of instrument training. Although Peterson was young, Dwyer had a high opinion of Peterson and stated he relied entirely on Peterson’s judgement.

While the ballroom rocked in Clear Lake, Peterson was at Mason City Municipal Airport (MCW) reviewing the weather. Conditions were VMC, and the primary concern was Fargo, where conditions were expected to deteriorate with an approaching front. Peterson checked on Fargo throughout the evening, where the front was arriving ahead of the forecast. As midnight passed, the ceiling at MCW lowered to 5000 feet and light snow started, with winds increasing from 20015KT to 18025G32KT. Forty minutes later when the musicians arrived, the ceiling had dropped to 3000 feet.

The flight would be made in a 1947 Beech Bonanza 35, N3794N. The airplane departed from 6500-foot Runway 17 and made a gradual turn to 315 degrees. Jerry Dwyer watched the aircraft from a catwalk outside the tower and saw the lights gradually descend several miles away. The first sign of trouble was Peterson not calling in the flight plan. Efforts to raise the aircraft were unsuccessful. As the night went on, word came from Fargo that the airplane did not arrive.

The wreckage was discovered the next morning after Dwyer took a plane out to conduct a visual search. It was found only four miles northwest of Mason City. The aircraft impacted the ground in a snow-covered field; with no houses near, no one heard the crash. There was no fire and all aircraft parts were accounted for.

Further investigation found the plane hit in a 90-degree right bank and nose-down. The damaged vertical speed indicator showed a 3000 fpm descent, the tachometer at 2200 RPM, and airspeed at about 168 knots. The propeller was broken at the hub, indicating that the engine was producing power. Investigators also found that the airplane had been properly maintained. So what went wrong?

The Weather

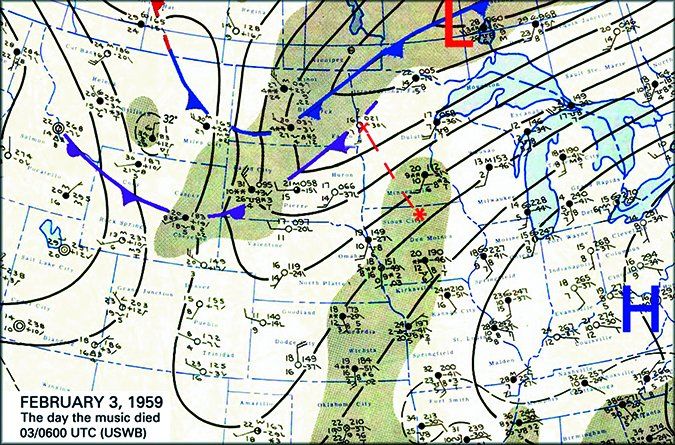

To understand the weather, we need to zoom out to a regional level and see what pattern was dominating. The surface chart (next page, top right) shows a classic polar outbreak pattern, with an Alberta clipper sweeping northwest-to-southeast. In the warm sector, where we expect to find southerly winds and meager tropical air, we find southerly winds across Kansas, Missouri, and Nebraska, but instead of typical February warm sector temperatures in the 40s and 50s, we find temperatures there in the 10s and 20s.

To compound the situation, upper level charts revealed a large trough extending from the Dakotas into the Desert Southwest region. This placed the area under southwesterly flow. A good rule of thumb is whenever a cold air mass is in place and winds aloft are southwesterly, you can expect clouds and precipitation.

This is called a “warm advection” pattern. Air is forced to rise as it encounters the cold dome, and if there’s sufficient relative humidity, clouds and precipitation develop. In fact, during the cold season this commonly produces IMC due to stratus, precipitation, and fog. Strong south winds on the surface provide more evidence this pattern is in place.

The surface chart also shows moderate to heavy snow across Iowa, with visibility down to 5/8 of a mile at Omaha. Although the accident report and various Internet stories today refer to a flash advisory for heavy snow bearing down on Iowa, this advisory actually refers to snow showers being generated along the Alberta Clipper. This may have produced solid IMC and closed down airports temporarily near Fargo, but it would have had no effect on the Bonanza’s departure.

Our main concern is with the widespread snow from eastern Kansas into western Iowa. The atmosphere is relatively stable here, but this can be a good setup for bands of moderate to heavy snow and sleet, which meteorologists sometimes identify as being caused by something called “slantwise convection.” It’s far too technical to describe here, but we occasionally see it within warm advection patterns where there is strong forcing. All of this bad weather was increasing in coverage to the west and rapidly closing in.

Soundings Fill In the Details

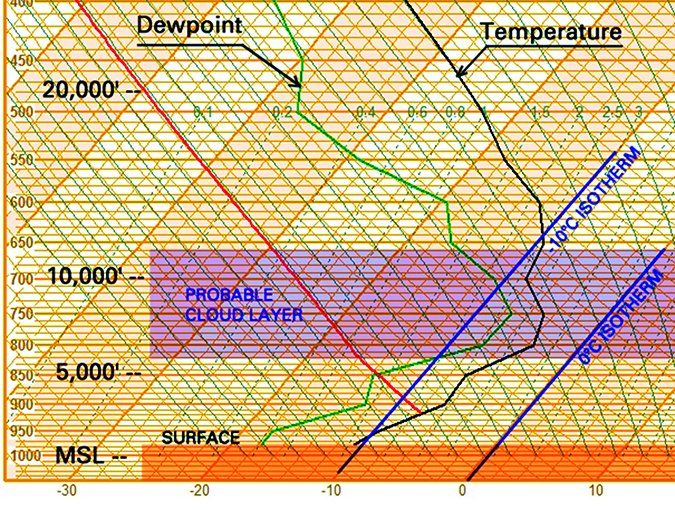

The sounding (lower right) gives our best picture of icing risk. As expected in a warm advection scenario, we see an inversion extending up to 7000 feet. Through this inversion the temperature warms with height, reaching a peak of -3 degrees C at the top of the inversion.

The other important piece of information is relative humidity. We determine this on the Skew-T chart by measuring the distance between the temperature and dewpoint lines. The smaller the gap, the higher the relative humidity. A good rule of thumb is when they are separated by 5 degrees C or less, the relative humidity is 70 percent or more, and there’s a high potential for cloud material.

On the Skew-T shown, we’ve shaded the band in light blue which likely has cloud layers. We have to keep in mind that this diagram is a single snapshot of the atmosphere, and conditions may vary around the region. This diagram indicates a cloud base of around 6000 feet, approximating the layers observed earlier in the evening at KMCW, but conditions were quickly deteriorating as the evening progressed and the weather system approached from the west. This would lead to a thickening of the cloud layer and extension of the cloud base downward.

The chart also indicates the potential for abundant supercooled water in the cloud, especially with most of the low levels falling within the dangerous 0 to -10 degree C clear-ice risk zone. This risk is realized whenever the temperature-dewpoint spread is 5 degrees C or less, as we outlined above.

It’s likely that investigators dismissed icing due to snow being reported and the short flight time. However this was a very dangerous pattern and I have many doubts that the flight could have made it to Fargo safely. As someone who has briefed thousands of pilots flying T-37s on up to B-1Bs and C-5s, I would absolutely not have boarded a small airplane with no de-icing capability if I saw these charts, unless the system was east. Even with a good pair of de-icing boots, I would be concerned. Warm advection patterns are nothing to mess around with.

The U.S. Weather Bureau forecasters of 1959 agreed. From the CAA accident report: “The temperature and moisture content was such that moderate to heavy icing and precipitation existed in the clouds along the route.” A second flash advisory issued at 0015 CST identified freezing drizzle within cloud layers being reported in eastern Kansas, producing moderate to heavy icing. This would have rapidly spread north during the night with the strong low-level flow. Unfortunately there is no evidence that the pilot received any of the advisories.

The Investigation

There was no CVR or FDR, of course, and no radio contact, so we can only speculate what happened in those final moments. The bad weather and snow are often associated with the crash, and at first glance seem the most likely culprit.

However investigators found one unusual piece of evidence. The aircraft was equipped with a Sperry F3 artificial horizon. This would be considered unusual by today’s standards. This is a design in which the ball is kept fixed with respect to the ground, unlike conventional designs in which the pitch axis rotates in an opposite manner to give the picture we are all so familiar with.

Experts concluded that this unusual presentation, along with the pilot’s young age and the fact he had been trained only in aircraft that used a conventional artificial horizon, pointed to the cause of the accident being disorientation. In short, it is thought he began referencing the Sperry gyro shortly after takeoff, became confused, and began losing control of the airplane. As the lights of Clear Lake moved behind the plane off to port and the plane began entering the diffuse cloud base, the pilot would have lost all his remaining visual references.

The CAA investigators also stated that confusion with the Sperry gyro was well known even to experienced pilots, particularly during transition periods and when alternating between the two types. The directional gyro was also found to be caged, which would have added even more confusion. Another theory suggests that not only the unfamiliar gyro behavior but the “inverted” color scheme of the gyro, with black “ground” at the top and goldenrod “sky” on the bottom, may have added to the confusion.

There still remains a possibility that weather was a factor, and this has some merit given the primitive state of forecasting, aviation forensics, and remote sensing in the 1950s. However, there is still no conclusive evidence with what we have available. As we have seen, there was great potential for icing, but the flight was not yet in the cloud where the majority of supercooled water would be found, precipitation near the ground was mostly in solid form, and at this stage of the flight there wouldn’t have been much time for ice to accumulate. With the weak instability, it is very unlikely that a convective downdraft caused a control upset. However with dry air below the cloud base and gusty winds, we can be reasonably sure that mechanical turbulence is likely to have bounced the airplane around, adding to the pilot’s misery.

Whether the music really did die with Holly, Valens, and the Big Bopper is a debate for another time and maybe another magazine. Many of us grew up on artists like Led Zeppelin, Rush, and Red Hot Chili Peppers. But there’s absolutely no doubt the events of 1959 still have a thing or two to teach us about meteorology. Those same weather patterns return to the Midwest almost every spring—the issue is what you will do when you encounter them.

Tim Vasquez is not in a Chevy at the levee but in Palestine, Texas where he works as a forecaster, programmer, and textbook author.

Great article. I am an aviator AND a Buddy Holly fan and often wonder what the world would have been like had he survived. I rode my motorcycle out to Clear Lake and Mason City a few years ago. Very sad. Gives us all a chance to do some introspection as we consider weather. Bye Bye, Miss American Pie….