If there’s beauty in simplicity, then there are few things quite as pretty as a flight plan that’s filed, and cleared, direct from departure to destination, with nothing in between.

However, to paraphrase a 19th century German saying, “No plan survives first contact with implementation.” As many pilots out there find out on a daily basis, just because one files or requests direct, doesn’t mean one gets direct. Some days, you luck out. Others, a few ATC clearances can turn that sweet little route into a bloated monster.

There’s perhaps some confusion among pilots about how a direct route gets handled and, potentially, mutated, as illustrated in one IFR-reader’s question: “If you file direct, is your route planned by some poor guy at the local TRACON or a regional computer? To what extent does putting in a few fixes affect the route ATC gives you?” Let’s see if we can clear up that haziness.

A Distinction

We’ll kick off with a clarification: Controllers aren’t route “planners.” Only someone with authority over that flight—such as the pilot or a company flight dispatcher—can perform what could be considered flight planning or route planning.

ATC doesn’t know each aircraft’s fuel, weight, equipment (beyond the filed suffix), performance limits, or other restrictions. What we do is control the flow of air traffic. To do that, we employ vectors, speed and altitude restrictions, and route amendments.

It’s the pilot in command’s responsibility to advise the controller if he, based on his planning, can’t safely comply with those instructions. Perhaps, ATC is re-clearing you over GPS fixes or via T-routes, not realizing your aircraft has a /A equipment suffix with only DME and transponder, with no GPS. We’re clueless if a route amendment adds a bunch of miles to your journey, for which you don’t really have the fuel range.

That’s where your flight planning and implementation of 91.103 on “Preflight action” enters into play. You—and not ATC—know your true capabilities and what’s in your fuel tanks. As the flight planner, you wield the knowledge. Please speak up if your limits are getting pushed.

As You Wish

On to the meat of the reader’s question: how does what you file affect what ATC actually gives you? Are those amendments made by humans or computers?

The simple answer to the first part: ATC will generally clear you via whatever you filed, unless circumstances demand a modification. We figure that if you filed it, you did so for a reason and planned your flight accordingly. It doesn’t matter to us whether you filed directly from Point A to Point Z only, put in “a few fixes,” or threw everything from B through Y in there as well.

If you go to a restaurant and order a steak, you should get what you ordered, unless a situation arises where it’s impossible or excessively complicated, like the kitchen running out of beef or the grill breaking.

We don’t make changes to your route “for controller amusement.” Most controllers actually prefer to give direct clearances, for reasons both generous and selfish. For you, the more quickly you arrive at your destination, the more precious time and wallet greenery you save. Simultaneously, the sooner you leave my airspace, the sooner I can stop worrying about you, pass you on to the next controller, and reallocate my attention to other aircraft still within my airspace. It’s mutually beneficial.

Airspace is designed to accommodate the traffic that needs to use it. If you’re flying in a military air base’s vicinity, you’ll likely encounter Military Operations Areas, Restricted Areas, or Warning Areas. Near a major Class B or C airport? Depending on your aircraft type and altitude, you may be threading your way on a SID or STAR.

The farther you fly and the higher the complexity of the airspace you’re transitioning, the more likely ATC may have a route change for you. Controllers, being in the safety and customer-service business, will generally say “yes” until, well, they can’t. The reality, unfortunately, is that established traffic flows often get in the way of your shortest path.

Under the Microscope

Your cockpit scan includes your instruments and the sky outside as you search for anomalies and traffic. Familiarity with your aircraft’s normal operating characteristics is critical to spotting and taking action when something veers from “in the green” to “needs attention.”

ATC’s scan is similar, examining equipment, airspace, and—naturally—the status of each aircraft under our watch. To answer the reader’s question, there’s no single “poor guy at the local TRACON” responsible for this. Every controller involved with your flight is trying to stay ahead of your requested flight plan—clearance delivery, ground, tower to departure, center to center, and finally approach to your destination tower and ground. It’s a team effort.

From the moment a controller first sets eyes on your flight plan, it’s being analyzed to verify it can be accommodated. That cross-check requires practical knowledge of local airspace, which controllers get drilled on from day one. Computer displays and status panels above or beside our stations show navaid outages, weather, special use airspace status, and other relevant conditions that may impede or alter traffic flow. This isn’t just situational awareness. It’s a key part of our job.

Now, each controller’s knowledge has range limitations. I’m completely responsible for my airspace, but not what goes on far outside of it. If I clear you to an airport 500 miles away, I have no real idea what the conditions are at your destination three centers and an approach control away. Once you get perhaps 50 miles from my TRACON’s airspace, my knowledge gets real hazy. I’m simply not “in the know.”

That’s why you get handed off to other controllers as you cruise along. Each subsequent ATC will again be checking ahead of your aircraft, using their own local knowledge to ensure your current route and altitude complies with traffic flow requirements. They answer the questions the previous controllers couldn’t, not because of lack of desire, but simply due to lack of available information.

A Helping HAL

Human eyes aren’t the only ones checking your route. Air traffic computers calculate your flight path from your departure airport to each fix along your route. If you file direct, it’ll “draw” a single line from A to Z.

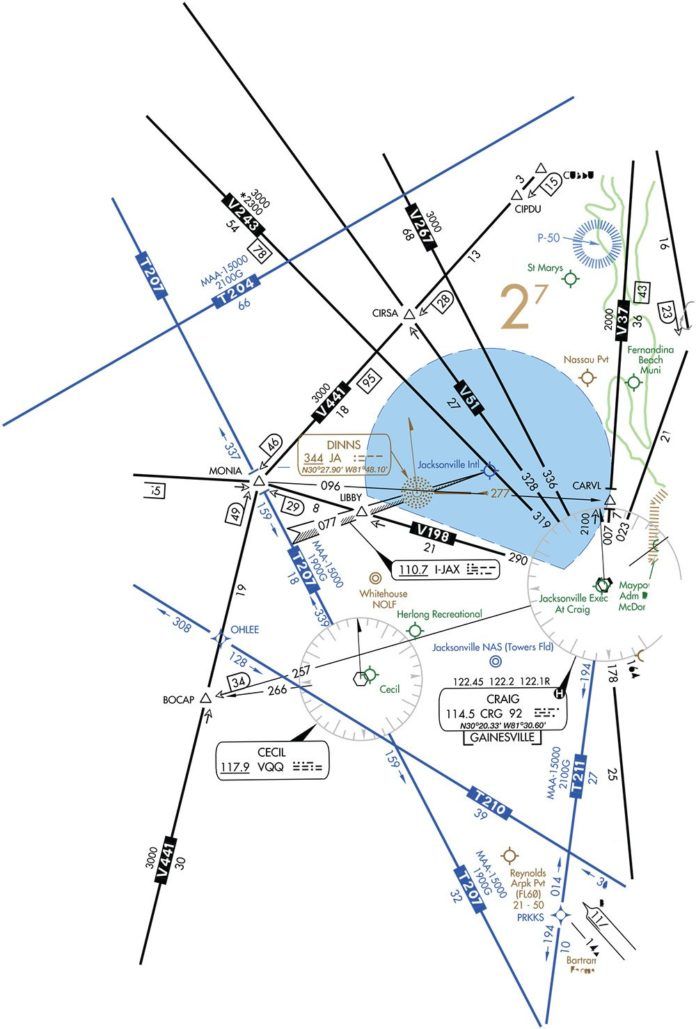

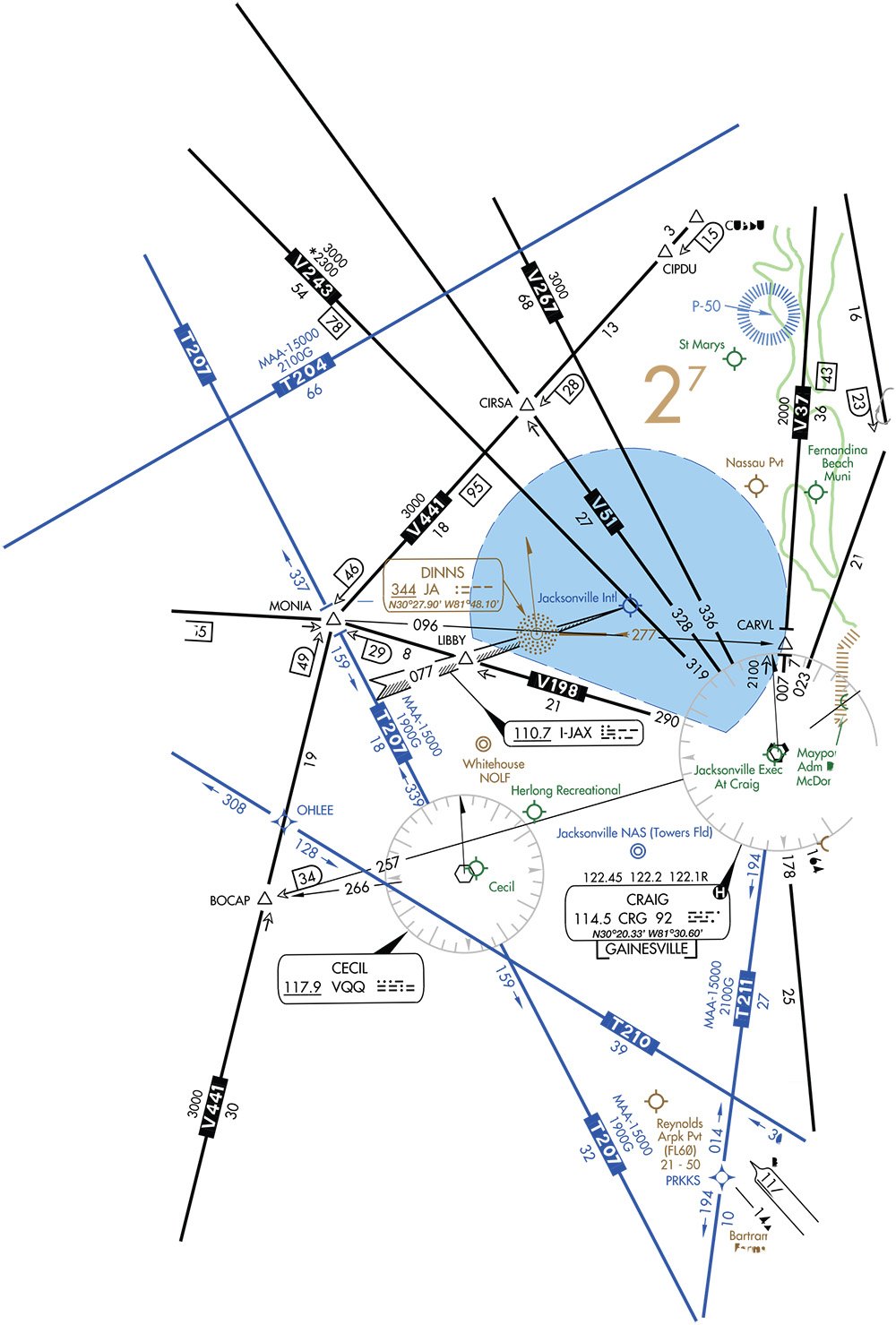

Taking into account your altitude, it knows which part of which ATC facility’s airspace you’ll be penetrating along the way. This removes a lot of guesswork. For instance, each ATC Terminal Radar Approach Control (TRACON) and En Route Center has multiple radar sectors. In the case of a center, they can have dozens, with usually high and low altitude versions of each.

When a TRACON is handing you off to its overlying Center, the controller usually doesn’t have to manually tell the computer to hand you off to a specific sector. The computer already knows to whom you should be talking, based upon that projected ground track it drew. The TRACON controller may just have to type “C” and click on your aircraft’s target. That initiates a handoff, and your target will start flashing automatically on the appropriate radar scope in the receiving Center.

Still, humans have final say. For instance, under certain circumstances—such as weather deviations—you may not be flying the track the computer expects. You may be about to enter a different sector, or on the boundary between two. The controller may need to temporarily amend your route in the system or verbally call the new sector to make sure you hand off appropriately.

So, with all this computer assistance, why not file direct all the time? As aviation quickly moves away from ground-based NAVAIDs and Victor/Jet airways towards RNAV and Q/T routes, it can be tempting to do just that, no matter how far you fly.

However, if you’re travelling a long distance and/or traversing multiple Centers, it’s still highly recommended that you file at least one fix within each Center’s airspace. This allows the computer to process your flight plan correctly, and allows the controllers working your flight to better visualize and protect your route.

Making Changes

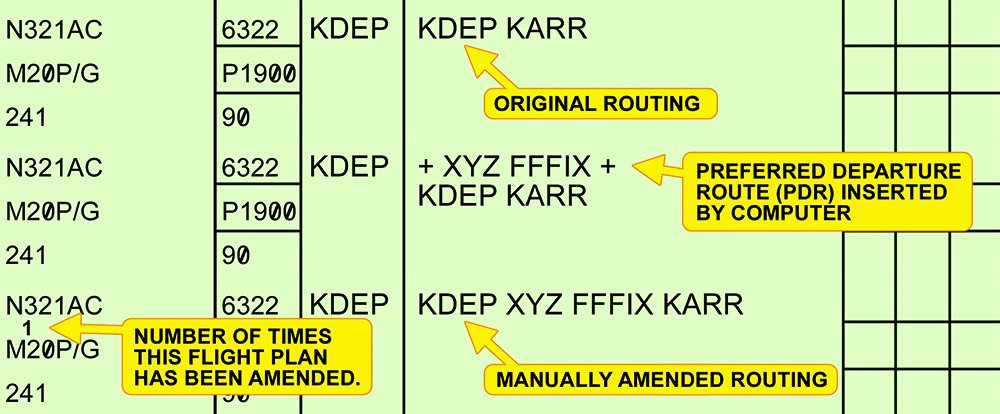

That’s a lot of eyes and tech watching your route. So, what actually happens when you file a direct flight plan? A three-step process is triggered: identify conflicts, amend the route if necessary, and re-clear the aircraft.

First, controllers or the computer recognize any problems. Here’s a situation: we have a Mooney filed out of our main airport at 13,000 feet, direct eastbound to his destination. If he had left before 9 A.M., direct would’ve been fine. It’s now 10 A.M. and an area MOA is now active. His on-course heading would drive him right through it.

Problem identified. Now, his simple direct route gets hit with a deviation in the name of a solution. When that MOA is active, our procedures require us to amend eastbound aircraft filed above 10,000 feet via the XYZ VOR, FFFIX intersection, and then back on their original route.

This was originally done manually for each aircraft, many times an hour. As you can imagine, this got cumbersome. After years of countless keyboard entries, our management sat down with our neighboring TRACONs and our overlying center and hashed out a new preferred departure route (PDR) containing the VOR and intersection.

Thanks to the computer programmers at the center—whose system “mothers” the TRACON systems—eastbound IFR flights filed above 10,000 feet now automatically get the PDR inserted whenever the MOA is active. When the MOA goes cold, we call up the center and they switch off the PDRs. This relieves a lot of keyboard work.

Route amendment in place, we need to clear the pilot. In the Mooney’s case, his PDR would automatically print out on a departure flight progress strip in the control tower. When the pilot calls Clearance Delivery, the controller will already have the computer-amended route handy. Any other aircraft that were already airborne when the MOA went live would need to be manually amended by the approach controller.

While ATC would sure love to give you direct, circumstances and established procedures don’t always allow that. When you plan your flight, look out for trouble spots ahead on your route, and see what kind of trouble may crop up. Sometimes you get lucky, but when you don’t, it’s nothing personal. We’re just doing our job.

Tarrance Kramer vastly prefers to say “Cleared direct….” over “Standby for full route clearance.”