New airports often mean flying procedures, or parts thereof, you might not have flown before. Unfamiliar approaches can also pop up at airports you thought you knew well. When you’re down to one choice due to weather conditions and limited equipment, well, then, you’re just gonna have to decide if you’re up for trying something new.

Planned and Unplanned

This is your third trip to Columbia, Missouri (KCOU), where you’re flying in from the northwest in your trusty but basic Cessna 182. Equipment includes dual nav receivers, one glideslope receiver and DME. (For those of you watching at home, this is pre-RNAV Distance Measuring Equipment.) A portable GPS offers limited capabilities to navigate outside of your raw-data setup. No big deal; you’ve been flying this plane and panel for years and are a pro with ILS approaches. The filed route, which will be reversed to get home, departs from Watertown, South Dakota (KATY) and is: POEMS OTG V175 HLV.

Looks simple enough, but the curious will draw out this course and see all the zigzagging required to follow Victor 175. This isn’t the most efficient way to reach KCOU, but there are no convenient airways and you have two advantages. First, this route skirts the large Crypt MOAs in northwestern Iowa and so takes military airspace safely out of the picture.

Second, given the 182’s equipment, there are enough VORs with nearby alternate stations to allow you to stay on the needles throughout. You also have the option, that you used on your last trip to Columbia, to ask for more direct routing via the Fort Dodge and Kirksville VORs when the MOA is cold.

You also like having the Hallsville VOR at the end of the route in case of lost comms; it’s on the airway, it’s an initial approach fix and so offers an easy place to pull over and hold if the need arises. All’s well for most of the trip, and you do get a shortcut from Kirksville direct Hallsville. Nearing Columbia, ATC says: “Expect vectors to Localizer Back Course Runway 20.”

Think Back

Really? There’s a brisk south wind prompting ATC to advertise the default approach, but how about a circle-to-land from the ILS 2? VOR 13? Anything else? Denied, due to conflict with traffic using 20. Besides, bases are dropping towards 500 feet and you’re not in the mood for a low circle. Seems like everyone else is asking for and getting the RNAV 20, but you’re stuck with limited capabilities. Back course it is.

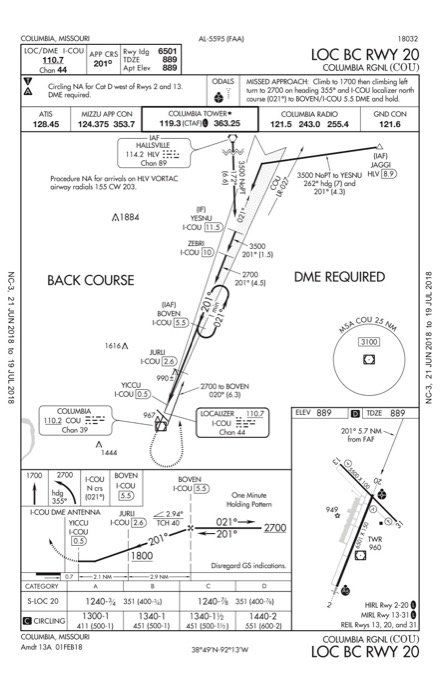

The first task is to pull up the chart and dig into the mental files for back-course basics. You know that a back course is often available as an add-on approach to an ILS. Then there’s that whole thing with flying course corrections away from the needle, not towards. The mantra “fly away from the needle” isn’t foreign to you, but was archived about a minute after you got your rating. You tell yourself that if you can make it down unscathed, you’ll spring for that HSI and always be able to correct toward the needle by always putting the course pointer on the front course. (See “Reverse Sensing—HSI” in July 2016.)

As it happens, you’ve forgotten that the signal and sensitivity are similar to what’s expected on the front course (10 degrees left and right of course when nearing the antenna), so you’re up there getting vectored, thinking it’s going to be less accurate than a regular localizer. You also failed to notice on the chart that the back course’s missed approach point is going to be a half mile before the threshold (since the localizer antenna sits at the arrival end of Runway 20).

Not the Usual

You do notice that the chart offers three reminders to use the back-course technique. For starters, it’s called LOC BC. Next is the localizer feather symbol on the plan view. The shaded half of the feather is on the left side of the inbound course, indicating it’s the “back” of the localizer signal for Runway 2. The third reminder is the BACK COURSE note on the plan view. Too obvious? Perhaps, but for those who are not as digitally challenged, there are little ways this could catch anyone by surprise.

First off, none of the other components of the approach chart—briefing strip, profile view, airport sketch—indicate this is a back course, not even the minimums table, which simply says “S-LOC 20.” It’s entirely possible to miss the “back course” part at first glance if you’re opening the approach on a tablet and zooming right into the profile view or minimums. What’s more, it’s well within the realm of possibility that you’d miss the “back course” part of the approach title as stated by ATC if you’re not expecting it. This happens quite a bit when you’re getting unexpected instructions at a busy time.

By the way, this procedure also requires using that DME as stated on the plan view. You’ll need it to identify the final fix, BOVEN. Now that you’ve briefed the procedure, you see that the approach, while an uncommon one, gets you the same results as those with basic RNAV. If you have localizer and DME receivers, you can get into KCOU with 351 feet and 3/4 mile, the same as the RNAV 20’s LNAV minimums. And the localizer portion of the ILS only nets you 40 more feet. Unless it’s down to LIFR at 300 or 200 feet, you have as good a shot at getting into KCOU as anyone else.

By this time you’re cleared for approach and while you’re nervously correcting a two-dot deflection on the way down from JURLI, you do remember to fly away from the needle and manage to break out just a couple of degrees off course before the MAP.

Let’s Go Again

Twenty-four hours later, you’re on the way back to Watertown with similar flight conditions—south winds and medium-low ceilings. Your trusty VOR 17 approach has an MDH of 460 feet, while the LOC BC goes to 339. You could use the extra margin. And now that you’re a whiz at this back course stuff, why not give it a go? Vectors away from the needle and towards the inbound. This time the intercept is spot on, and you realize with great satisfaction that a perfectly flown back course looks just like a front course.

Elaine Kauh is a CFII in eastern Wisconsin, where she keeps a couple of LOC BC approaches in her back pocket for those unsuspecting pilots who’ve become overly attached to ILS.