In June 2017, President Trump led off Infrastructure Week with his plan to move ATC to a nonprofit, private corporation. With two bills already in Congress, D. J. Gribben, special assistant to the president for infrastructure, called it “low-hanging fruit from a policy perspective.” Little did he know how incendiary the word “privatization” is to the aviation community. Mr. Gribben often uses this word, but savvy proponents avoid it and even refute those who use it.

Not Privatization

They’re right. It’s not privatization according to The American Conservative Union Foundation’s seven principles of privatization. Applied to H.R. 2997, the “AIRR” Act, it failed to meet five of the criteria.

Over 200 aviation organizations opposed AIRR and it never made it to the House floor. Meanwhile, the Senate Appropriation Subcommittee rejected the proposal for fiscal year 2018 and aggressively rejected the concept altogether.

On January 2, Rep. Bill Shuster (R-PA), Chairman of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee and author of both House bills, announced he would not seek reelection beyond his ninth term, partly because his chairmanship expires. No one is picking up the torch to continue his fight.

Shuster announced he would spend his last year focusing on passing the much-needed infrastructure bill. Such a bill could include ATC privatization if omitted from an FAA bill.

Many expect Shuster to double-down, even though the proposal is effectively lifeless. “It’s pretty well dead,” said Peter DeFazio, (D-OR) a critic of privatization and top Democrat on Chairman Shuster’s transportation committee.

Now What?

AIRR was called a “solution in search of a problem.” More accurately, it’s “two problems in search of solutions.” The larger problem is to ensure steady, reliable FAA funding. The more difficult problem is restructuring the FAA to help it modernize more rapidly and efficiently, with a focus on NextGen and emerging technologies.

In his last speech as Administrator, Michael Huerta called these problems the “800-pound gorilla.” “Today, a debate is raging in Washington about how the FAA should be structured and funded. It is a conversation that is long overdue, and one in which all of those with a stake in the future of aviation must be included.”

He stated the core problem: “Since [I joined] the FAA, the government has been ‘shut down’ twice and faced sequestration. In addition, the FAA has dealt with [23] short-term reauthorization extensions. That is not how the world’s best aviation system should be run.”

Congress funds the FAA mainly via aviation-related taxes and general funds. As of this writing, the FAA is funded until March 31. Although reauthorization is a congressional matter, the FAA gets blamed for delays and inefficiencies resulting from stop-and-go funding.

In 1995-1996, Congress mandated personnel, acquisition and organizational reforms. Two acquisition reforms were only implemented in 2004 and 2012. Four organizational reforms waited until 2003-2011. However, the FAA did flatten its organizational structure and efficiently consolidate resources.

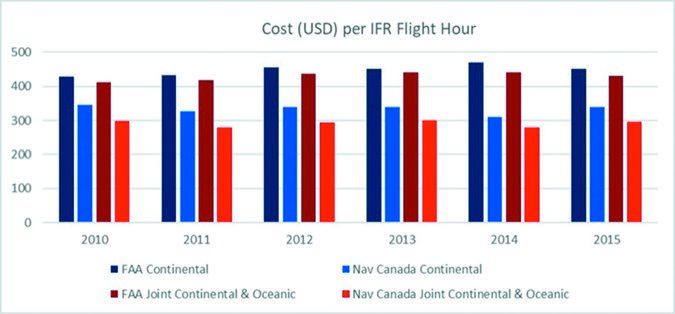

Yet, costs have neither decreased nor has productivity improved. Why? Calvin Scovel, DOT Inspector General, outlined the issues in May 2017. He cited the FAA’s failure to take “full advantage of its authorities when implementing new personnel systems or use sound business practices to improve its operational efficiency and cost effectiveness.”

The FAA outsourced FSS in 2005, saving about $2.13 billion over 13 years. The Federal Contract Tower Program saves about $1.5 million annually per tower. But, the FAA hasn’t converted any of its towers to contract towers since 2000.

Next Up: H.R. 2800

Two days after the president’s announcement, Rep. Peter DeFazio (D-OR) offered his own bill, the Aviation Funding Stability Act to “ensure improvement of air traffic control services.”

The bill would exempt the Airport and Airway Trust Fund (AATF) from sequestration or appropriation, making funds immediately available to the FAA. Treasury funds would also be sequestration-proof. Both measures would help stabilize funding.

The FAA could transfer funds into administration operations “to prevent reduced operations and staffing and ensure a safe and efficient air transportation system,” thus avoiding furloughing about 8000 (out of about 46,000) FAA employees during a government shutdown.

Simplifying procurement, the FAA would be exempt from OMB rules. Until 2030, uncommitted AATF funds could be used to maintain and modernize any ATC facility, most of which are 30-plus years old.

This gives the FAA independence from all acquisition laws for NextGen. The bill calls for “private-sector best practices for major capital investments in information technology, telecommunications, and other relevant systems.”

Easier said than done, given the FAA’s “not invented here” syndrome, bureaucratic resistance, and politics. Consultant Robert Poole wrote in 2013, “The agency is particularly resistant to high-potential innovations that would disrupt its own institutional status quo…” But privatization would be more difficult still, with an unpredictable outcome. Nor would it solve all the problems.

Predictably, the FAA opposes privatization. In 2016 they said, “governance changes should work to solve the challenges FAA faces, not just reshuffle the organizational structure. Any movement away from the present model needs to ensure more direct accountability to our users and be mindful of the linkage and integration of safety, NextGen, airport infrastructure, and other functions.”

NextGen

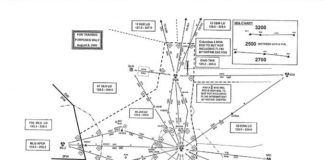

NextGen is intended to enhance airspace capacity, reduce delays, and reduce aviation’s environmental impact. In 2008, the FAA identified six “transformational” prerequisites for the midterm phase of NextGen to “transform” management of our airspace system.

However high-minded, not all will transform the system as the FAA originally envisioned. In early segments, limited transformation occurs. Later portions remain undetermined.

Unrelated programs have been grafted onto NextGen. For instance, the National Airspace System Voice System (NVS) will enhance and modernize ATC voice communications—good, yes, but not essential for NextGen.

A 2015 National Academy of Sciences study said that NextGen, depending on the audience, ranged from transformational to a set of incremental changes. In mid-2017 the GAO concluded that NextGen is primarily an incremental modernization effort. They perceptively noted that NextGen must evolve even during its development to account for technology advances against changing demands. FAA officials contend that NextGen is both incremental and transformational.

Money

In early 2017, the FAA said it spent $7.5 billion on NextGen in the last seven years. They claimed this had resulted in $2.7 billion in benefits to passengers and airlines and will yield more than $160 billion in benefits through 2030.

The Inspector General took the FAA to task for not clearly stating the total costs, capabilities, or completion schedules for any of the six transformational programs. Estimates for these programs now total over $5.7 billion, and completion has been pushed beyond 2020. Many programs are unclear on how they will improve air traffic flow or controller productivity. Since the FAA has not yet determined when most of the transformational programs will begin delivering benefits, it’s just one more uncertainty in an ocean of ambiguity.

Organization

Because the transformational programs interact, the FAA needed a more granular approach than the original segmented, phased implementation. For example: More efficient routes are useless without tools to better manage airborne traffic. To help manage NextGen across programs, FAA organized operational NAS improvements—such as enhanced ATC procedures—into 11 “portfolios.” This holistic approach views NextGen as an integrated effort, not separate programs.

Management

Understandably, FAA management focuses more on safety and less on factors like cost efficiency or productivity enhancement. This also makes it easier to justify the status quo when making cost and operational decisions.

The since-departed Mr. Huerta said that “long-standing management problems have led to further delays with FAA’s efforts to deliver new technologies and major acquisitions.” Even so, his administration made real progress on NextGen.

The FAA must both improve services today and prepare for increasingly sophisticated users. Congress must allocate funds to help the FAA maintain its safety focus, continue modernization and make sure the airspace remains open to all.

Privatization isn’t dead and it probably never will be. If the FAA’s issues cannot be efficiently resolved, privatization may once again become a serious proposal.