The National Air Traffic Controller Association annually presents safety awards to members who have saved pilots’ lives through teamwork, skill, and persistence. Rather than talk about accidents, this article discusses some of the many saves that never make the headlines. The saves below are excerpts from the award citations.

Winter’s Worst

In January 2022, a Socata Tobago was inbound to Manassas Airport in Virginia. It was snowing, and the winds were strong. As the pilot reached about 10 miles north of Frederick Airport (KFDK), he reported turbulence, engine ice ingestion, and low-vacuum problems. ATC tried to set him up for the straight-in ILS approach to Runway 23 at KFDK to get the pilot on the ground as soon as possible, but the Tobago overshot the localizer.

At that point, ATC declared an emergency on his behalf. Meanwhile, they attempted to assess the airport. Frederick reported that the airfield had not been cleared, and no aircraft had landed recently, so conditions were unknown. The pilot flew a second approach which also failed.

The third time, ATC set the pilot up with a longer inbound course, which allowed the pilot to get better established. He reported, “I’m getting bounced all over the place, sir, very violently,” and was now dealing with a sputtering engine and autopilot issues. As the aircraft neared KFDK, the pilot started to dip below minimums. The tower turned the runway lights up full, and the Tobago landed safely.

Once the pilot was on the ground, he called the facility to thank the controller, saying, “I just wanted to thank you personally. That motor was sputtering, my gyro was freezing up, you were unflappable. That last correction put me right on the ILS and made all the difference.”

Caught Over the Chesapeake

An inexperienced instrument-rated pilot planned an IFR trip from Hagerstown, Maryland (KHGR) to Shenandoah Valley Regional Airport (KSHD) in a Piper Archer. He quickly ran into trouble. He had wanted to descend and fly VFR along Interstate 81 at 2000 feet. His initial mistake was entering IMC at 5000-6000 feet, at which point the Interstate 81 option disappeared.

ATC realized he needed special attention and an instrument approach into the unfamiliar airport. It was windy, and the pilot had difficulty flying straight and level. Both KSHD approaches were completely new to him, and his onboard GPS sent him off course. Being tired, he became confused and uncertain about his location.

ATC directed him to the KSHD localizer, but the pilot was at first unable to pick it up or stay on the localizer. ATC told him to go around. Having realized his inexperience, ATC limited the number of corrections, turns, and length of turns on his second attempt.

The controller gave him confidence. “It was almost a surprise when I popped out of the clouds because I was focused on doing exactly what he said. And once I popped out of the clouds, I was just joyful in telling him, ‘Airfield in sight!’”

Descending Spiral in IMC

A pilot and his wife were flying IFR in their Cessna 210N to Cumberland Regional Airport in Somerset, Kentucky (KSME). The weather started to deteriorate.

An Indianapolis Center controller noticed the aircraft’s track change to a southerly heading. Asked if he was deviating for weather, the pilot said no and corrected his course to Somerset. Soon after, the KSME airport manager called the Center to report a low-flying aircraft. The pilot missed his approach. On the radio, he seemed disoriented and had trouble flying the aircraft.

ATC devised another plan to send the aircraft to London-Corbin airport (KLOZ). They noticed heading and altitude inconsistencies en route. The pilot said the aircraft was on autopilot and coupled to his GPS. Center tried to get him on a portion of the approach at LOZ, but that didn’t work out.

ATC then issued multiple headings and a minimum altitude to maintain. The pilot seemed to enter a dangerous descending spiral, exiting IMC only a few hundred feet above the terrain. The pilot confirmed visual contact with the ground. At the risk of their lives, he landed safely at KLOZ.

Double Trouble

The inland weather in Houston was IFR with low ceilings, but better near the coast. The controller accepted a handoff from another controller who dealt with a Skyhawk in distress, making tight circles and descending in IMC. That controller got the aircraft straight and level and on a radar vector before the handoff. The new controller vectored the Skyhawk to Ellington Airport (KEFD), southwest of downtown Houston.

The 172 was still in trouble and could not join the final approach course for KEFD. The pilot requested a visual approach at Galveston (KGLS). The controller supplied a vector and calmly talked the nervous pilot down through clouds, avoiding turns and minimizing his time in IMC.

Complicating matters, another 172 was practicing approaches in the area when they experienced a cabin fire and appeared to be losing altitude. Without missing a beat, the controller gave the pilot information about Galveston airport and obstructions en route. They were able to extinguish the fire and regain control of the airplane.

Both aircraft made successful visual approaches at Galveston. The controller probably saved several lives that day.

A Mooney Acclaim departed IFR from Westchester County Airport in White Plains, New York. His departure instructions were a 90-degree left turn and a climb to 3000 feet.

The departure controller immediately saw the pilot flying erratically. The tower told him to return. The weather was solid IMC with 1.5-mile visibility and moderate snow. At 1500 feet, the pilot requested to return.

When asked if he wanted to declare an emergency, the pilot explained that he had lost his autopilot and GPS. The controller got the pilot lined up for Runway 16 on a three-mile final. About a mile out, he spotted the airport and landed.

The controller found out later that the aircraft suffered a total electrical failure. The pilot used the wet compass for the headings being issued to him. No wonder he told ATC he couldn’t accept an ILS.

Out of Breath

The single-engine Socata TBM 930 departed Paducah, Kentucky, for Houston, Texas. Soon at altitude, the pilot experienced problems controlling the aircraft and was unresponsive to ATC calls.

Thinking of hypoxia, the high-altitude controller at Memphis Center regained communications and coordinated a lower altitude with the low-altitude controller. On check-in, the pilot seemed disoriented and had difficulty maintaining altitude. The pilot confirmed that the TBM had lost pressurization.

ATC suggested McKellar-Sipes Regional Airport (KMKL) in Jackson, Tennessee, to avoid thunderstorms and heavy precipitation. While the pilot pondered that, the controller alerted the tower of a possible emergency headed their way. The pilot requested MKL, and he was cleared there at 3000 feet.

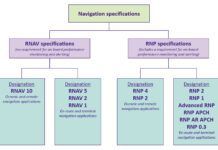

MKL had marginal VFR with a broken layer at 1000 feet and overcast just below the MIA. A heart-stopping moment came after the pilot said he was “having a little trouble … controlling the plane for some reason” just as the TBM descended below the MIA. ATC immediately informed him of nearby obstructions and guidance to avoid them. The controller led the TBM to the RNAV for Runway 20, and it landed safely.

Ellington Again

On another day, the weather at Ellington Airport in Houston was IFR, with ceilings at 800 feet. A Piper Cherokee was cleared for the ILS 35L. The controller noticed the Cherokee was struggling to stay on the localizer. Even so, the controller established him on the approach on the first try.

Soon he noticed the Cherokee wander off the localizer. The pilot began a climbing right turn, then called to report that his (unspecified) gyroscope had failed. The pilot requested vectors for a second try, despite his seeming inability to maintain altitude. The controller declared an emergency for the pilot as other controllers vainly sought an airport with better weather.

On his second attempt, the Cherokee got back on the localizer but soon descended in a tight, steep turn. His altitude sank from 2400 to 2000 feet. Despite not wanting to take control of the airplane, the nonpilot controller told the pilot to roll right and pull back on the yoke.

The pilot didn’t acknowledge but soon broke out of the ceiling at 700 feet and reported he could see the ground. He happened to be in an area free of obstructions and traffic. When the pilot reported he could see KEFD, the controller issued him a contact clearance (a technical no-no), and the pilot landed safely.

Another controller relieved him while he took an hour to collect himself, saying, “This was the most traumatic event of my career, by far.” But his efforts helped save two lives.

ATC Finds a Way

A Cessna 172 missed the RNAV 17 approach at Clinton Regional Airport (KCLK) in Oklahoma and requested another attempt. The KCLK weather was low: 1.5 NM visibility and 400 feet overcast. The Cessna missed again. Failing to fly the published missed approach, the controller knew the Cessna was in trouble. A PIREP indicated that Lawton-Fort Sill Airport (KLAW) had bases at 2000 feet but was 64 NM away. With just 14 minutes of fuel left, the Cessna landed there after flying a surveillance approach.

Thank you, ATC

ATC has a deep bench. Pick up the mic and ask for help when you need it. You’ll be glad you did.