No matter how carefully you plan, problems seem to appear. But they can be mitigated exercising care in planning, situational awareness, and knowledge. Here, we focus on knowledge to help you gain that essential element of situational awareness to build on the rules of thumb you’re originally taught.

Let’s look at the transition between spring and summer: May through July. It’s a popular travel period. With crowded ramps, tight itineraries, extra passengers, and the haphazard convective weather, it pays to have a firm grasp on the weather patterns this time of year.

Big Picture

The late spring warmup in the northern hemisphere and layoffs at the “polar air factory” cause cold fronts and jet stream patterns become confined to Canada, the northern tier states, and the Great Lakes. But the warmup affects some areas and not others, shaping the weather patterns.

In the subtropical latitudes, there’s only a modest warmup. In San Juan, Puerto Rico the daily mean temperature warms only five degrees F between February and June. Cancun, Mexico, warms only eight degrees. Meanwhile, we see a warming of 36 degrees F in Boston, 41 in Chicago, and 57 in Churchill, Manitoba.

Once the Polar Regions are out of the icebox, there’s a strong reduction in the temperature gradient between tropical and polar latitudes, causing a pronounced weakening of the jet stream. The cold fronts are so feeble that they remain mostly in Canada, so the jet stream “shrinks” northward. Winds aloft in the United States weaken, and non-convective weather systems become significantly less organized. Severe weather also diminishes across the southern states.

Tropical cyclones are unusual before August through October. But in active years hurricanes may wander across Florida, the Carolinas, and the Gulf Coast as early as June. An early season storm looks possible for 2018, with the preliminary Colorado State University tropical cyclone forecast for above-average activity.

NASA/Terra

West Coast

Anyone who has tried to swim at a California beach would agree the west coast of the United States is dominated by cold ocean currents. These are prime areas for development of fog, stratus, and IMC. The atmosphere is chilled from below, producing a warm-over-cold profile, resulting in stable air and inversions that suppress upward motion and mixing of the air mass. When moisture infiltrates, the air is cooled rapidly to near its dewpoint, producing clouds and fog.

Normally this wouldn’t be of much concern. But, because of the high thermal mass of the oceans, the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans become cold compared to the landmasses during the warm season. This means high pressure offshore, low pressure inland, and a thermal circulation is often in place May through August. Air flows inland near the surface, much like the cool air flowing out of an open refrigerator door.

This means the advection of the cloudy “marine layer” onshore. The fog and low stratus tend to sneak in overnight, marching eastward and bringing places like Long Beach, Santa Maria, and the San Francisco Bay to IMC. The clouds generally persist well past dawn, usually burning off later in the day. While this might seem like a curse to pilots, California’s vineyards and coastal redwood forests depend on summer fog. Without it, the landscape would be baked and dried out by the sun.

The May 2013 issue ofIFRgives a more detailed explanation of this coastal fog and how to anticipate changes and work around it. If you’re getting in late and need to divert, the rule is “head inland”, where VMC usually prevails.

Wikipedia

Western Interior Regions

Hot temperatures come early in the desert Southwest. For example, Phoenix’s record of 122 degrees was set on June 26, 1990, while Las Vegas’s 117-degree record was most recently tied on June 30, 2013. There is not much soil moisture, and the surface consists mostly of sand, rock, and granite with low specific heat. If you’ve ever walked across a parking lot on a summer day, you have some idea of how rock soaks up the energy of the sun. Some heat is radiated away at night, but a lot of it is stored in the ground. So the Southwest regions are very hot by May.

These warm conditions often extend simultaneously northward into the Rockies and Great Basin region. The temperatures seem deceptively normal on the ASOS reports. But because of the high elevation, the density altitudes can be thousands of feet higher. So, a word to the wise: density altitude is a consideration far earlier than you might think.

The same heating that causes these hot temperatures and high density altitudes produces a large thermal low in the western United States. It’s usually centered in Arizona but may sometimes stray into adjoining states. The atmosphere responds by directing winds from the subtropical regions toward the desert southwest. This allows moisture to gradually flood northward through Texas, New Mexico, and northern Mexico.

This is the Southwest monsoon pattern. Weather there is usually divided into pre-monsoon and post-monsoon phases. May is normally the pre-monsoon time for all of the southwest. In June, it appears in New Mexico and northwest Mexico. By July it begins spreading from southeast to northwest across Arizona and into Colorado, and during August it reaches the Great Basin region and much of the northern Rocky Mountains.

Before the monsoon arrives, temperatures are hot and skies are mostly clear and blue. Once the monsoon arrives, cumulus build rapidly into cumulonimbus during the day, with thunderstorms during the afternoon. By dusk there are broken-to-overcast debris layers. These storms repeat daily, with the pattern gradually drying out.

Fortunately flying in a monsoon pattern is manageable with a little planning. Do as much of your flying in the morning as possible. Low-level wind shear is a major hazard around storms. Instrument conditions are rare outside of precipitation areas, but haboob events (see photo, above) from dusty storm outflow can knock visibility down for hours. If your destination is socked in by a storm, just land at an alternate field and wait an hour or two. You’re almost guaranteed that things will improve by evening.

NASA/Terra

Great Plains

Late spring on the Great Plains largely means the end of spring snow events, but the biggest change is the surge in instability. Solar heating during spring is initially focused on the lowest levels of the atmosphere, where sunlight hits the ground, and conduction and convection do their work. This means that the spring months bring a drastic increase in the cold-over-warm temperature gradient, in other words, high static instability dominates the spring months.

The flip side of this is the gradual decrease in polar air masses surging southeastward toward the Atlantic Ocean, and particularly into the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean. Each of these polar air mass outbreaks drives dry air into the subtropical regions and reduces the sea surface temperatures, dampening evaporation. When the cold fronts stop moving into these regions in April and May, the air mass becomes primed with moisture. This allows high humidity and dewpoints to move northward into Texas and Louisiana, and northward. The result is storms.

If you’re flying into the Great Plains region, look at surface charts and keep an eye on the dewpoint value, usually plotted in the bottom left of a station plot. This is useful over a period of days and weeks as a barometer for severe weather. During late spring, values under 60 degrees F indicate a marginal risk of thunderstorms and severe weather, while values over 70 indicate a significant potential for severe weather. This is especially true in May. By mid or late June, the upper atmosphere warms up, reducing instability and the chance of storms.

Another chart you can search for on the Internet is CAPE, convective available potential energy. This is widely a meteorologist’s favorite tool to evaluate instability. Values of over 500 indicate storms, over 1000 J/kg suggest severe weather is possible, and over 2000 suggest it is likely. These tools are best used in conjunction with the convective weather forecasts from the Aviation Weather Center.

Southeast States

The increased instability that affects Texas also affects the Gulf Coast region. Radiosonde observations show the average instability increasing from week to week.

Overall, the weather is good on the Gulf Coast in May. However afternoon “air mass” thunderstorms are becoming commonplace. Fly during the morning whenever possible. This will keep you out of the storms and give you smoother air.

The phenomenon of sea breeze thunderstorms begins in early May along the entire Gulf of Mexico coastline and the Atlantic from Florida to the Carolinas. In June, while weather systems up north graze the region, rain can be a significant hazard in the western Gulf Coast, especially from Houston to New Orleans. Thanks to moist southerly flow, sea breezes, and air mass storms, June is commonly the wettest month of the year for those locations.

By July, weather is comprised almost entirely of afternoon “air mass” thunderstorms, with organized sea-breeze storms on the Gulf Coast and Atlantic Coast. Things are often active during the afternoon everywhere, while at night, storms may occur offshore, particularly near the Gulf Stream waters off the Carolina and Florida coast.

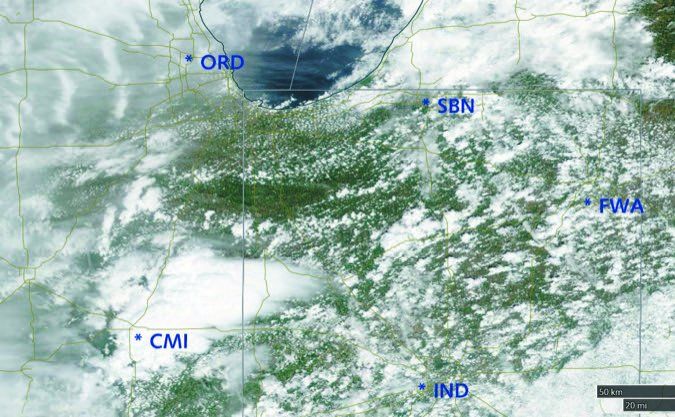

Midwest

The jet stream winds largely retreat northward to Canada by summer, but the Midwest gets countless fronts, upper-level disturbances, and jet stream energy that move through the region or even stall out here. These hazards affect the region all summer long. This means you’ll need to keep close tabs on TAFs, advisories, and planning products.

Another hazard is the nocturnal mesoscale convective complex (MCC), which tends to form almost nightly over Iowa, the Dakotas, Nebraska, or northern-Kansas farmlands. These MCCs are regarded as essential for the nation’s corn and barley industry. We quite literally owe our beer, taco shells, and cereal products to these storms, but they can be quite the headache for the aviation community.

Look for MCCs to be most active after midnight, particularly along stalled east-west fronts. They should never be penetrated without onboard radar. These storms tend to drift eastward, reaching the Mississippi or Ohio River region around early morning, and by this time the severe weather hazards are mostly gone. If you keep this life cycle in mind, you can anticipate what the storms will likely do when you see them. If an MCC is moving into Indiana at 7 a.m. and weakening into rain showers, you can expect they’ll be mostly gone by 10 a.m.

Occasionally, though, an active storm pattern can develop. This is characterized by a storm cluster that’s linked with strong upper-level winds or is fed by strong low-level winds. These storms can bring tornadoes, hail, windstorms and even the derecho windstorm. They don’t dissipate at dawn and can surge eastward into the Appalachians or Northeast U.S. Look at upper-air charts; weak winds are probably just the humble MCC. Winds of 60 knots and troughing suggest an active storm that warrants extra caution.

Northeast

Similar to the Midwest region, the Northeast states are affected by active weather systems in May, and are scraped all summer long by Canadian systems in Ontario and Quebec. This means that TAFs and planning products are essential for staying safe. Normally a quick glance at the surface and upper air chart tells the picture for the Northeast region—if winds are uniformly out of the southwest and upper winds are weak, this indicates visual conditions are very likely. If dewpoint values are elevated, though, afternoon “air mass” storms may pop up over higher terrain.

When organized storms occur, though, they’re likely part of an active storm pattern. Summer also brings the highest risk of severe weather; a quick Internet search shows the most prominent tornado outbreaks in the Northeast spanning late May through September. Winds and shear are major hazards. Large derecho storm complexes are a notorious hazard between late June and August, especially in upstate New York and adjacent regions. An afternoon squall line in the Great Lakes region with numerous warnings and strong upper-level winds is a sign of big trouble in the Northeast overnight.

Takeaway

Not only have we summarized the important elements we see around the United States in late spring and early summer, but we’ve also tied them to the dominant weather patterns. Perhaps the most important thing you can do when looking at weather charts is visualize what’s happening, link the weather to the systems driving the patterns, and go back to basics wherever possible to understand the big picture.