Oops! (Damned Autocorrect)

I only realized after reading my published article, “DA Versus MDA” in the June issue, that Master CFI and DPE, Larry Bothe’s name got munged. I checked my original copy and, well, the error was on my end and I assume it’s a result of unbridled autocorrect.

My apologies to Mr. Bothe.

Jordan Miller

Peachtree City, GA

Squawk Again?

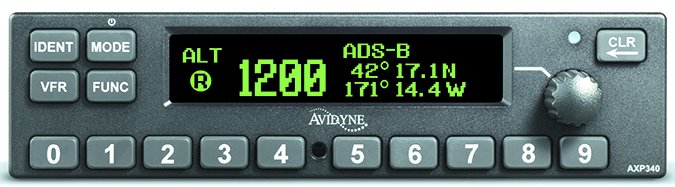

I found the reader question and your response about squawking standby in the May issue interesting because Mode S transponders and especially ADS-B Out configurations have SBY/ALT positions when a GPS position is received rather than ON/ALT without a GPS position. At least that is how my Avidyne IFD540/AXP340 system works.

The transponder powers up in SBY mode and automatically switches to ALT mode during the takeoff run. Perhaps I’m wrong, but my understanding is that the SBY position has a different transmission profile for Mode S than the ALT mode and that is reflected in what ATC sees. That would be consistent with the ATC request to squawk SBY when on the ground. I wonder if the reader has this properly set up with his ADS-B configuration.

Vince Fischer

Wernetshausen, Switzerland

Today, there are multiple reply modes with which a transponder might respond. We’re familiar with Mode A (beacon reply only) and Mode C (beacon and altitude reply). For quite some time there’s been a Mode S (Mode C with additional identification) and now there’s ADS-B or Mode S extended squitter (Mode S with ADS-B enhancements).

The Avidyne AXP340, when properly installed, has the following user modes that reply as indicated: ALT (All available replies), ON (Mode A replies only), SBY (No replies), GND (ADS-B Out and Mode S replies).

Mode selection between ALT and GND is automatic; the unit removes the option for GND in the air and removes ALT on the ground.

Garmin takes a similar but different approach. It also provides a GND mode, but that is only automatic—not user selectable. Their user-selectable modes are: ALT (All available suitable replies for the current state—ground or in flight), ON (Mode A replies only), SBY (No replies)

Garmin’s user mode, ALT, automatically switches between GND mode and airborne mode as appropriate.

So, with both manufacturers, SBY stops all replies. A discrete UAT installation, however, might behave differently.

In May’s issue in “Readback,” a writer seems not to have gotten the word that the transponder rules changed over a year ago. In the surface movement area all transponders must now be squawking ALT, and if assigned a discrete code, that must be active as well.

Bennett E. Taber

San Francisco, CA

ASRS Story

I just finished reading “ASRS: Safe Protections” by Fred Simonds in your May issue. Good reminder story for all pilots (and ground personnel, ATC, etc.)

I recall a funny story from when ASRS first went live, although it could have been tragic. A private pilot flying a C-150 wanted to go from the north side of the Houston TCA (well before Class B) to south side of the TCA. The pilot didn’t wish to go around, because headwinds would have added about 30 minutes to the trip.

Knowing there was no way to obtain a clearance through the TCA at rush-hour, the pilot turned off the transponder, overflew IAH and HOU airports and exited the TCA to the south before turning the transponder back on. On landing, the pilot promptly filed an ASRS report, assuming it would provide immunity. The FAA tracked the pilot down and filed various charges. When presented with the ASRS report, the FAA rightly said that the act was deliberate and not protected by ASRS.

Barry McCollom

Kerrville, TX

MITRE Stands For … MITRE

In Fred Simonds’ April article, “A Kinder, Gentler FAA?” he talks about GAARD, an app written by MITRE. Unfortunately, Fred incorrectly said that MITRE is an acronym for MIT Research Engineering. That’s a common misconception, but MITRE is not an acronym; it’s simply the name of the corporation.

Vince Massimini

Location withheld by request

Airspeed Change Reports

I fly a Piper Arrow and I often get a routing directly over and parallel to the Appalachian Mountains. In winter and early spring with strong westerly winds, mountain waves are an issue at 8000 and sometimes even 10,000 ft. To maintain altitude you have to sacrifice airspeed. To maintain altitude for the up elevator as compared to the down elevator, airspeed can vary up to 30 knots.

Question 2 in June’s quiz sates, “Your true airspeed must be reported when it changes by more than five percent or 10 knots.” Does this also apply in the enroute environment with Center? I have never heard anyone report airspeed changes due to mountain waves.

Chuck Lacey

Frederick, MD

The reference, AIM 5-3-3.a.1(e), refers to your average true airspeed. So, no, you need not report transient changes to your speed from mountain waves. However, a report of the mountain wave is appropriate as a meteorological report, and one measure of the severity of the wave is airspeed deviations.

Oh, Those New Yawkers…

“Communicating with ATC” (May, 2016) was a great article by Tarrance Kramer. Successful communication is definitely a two way street. Unaddressed however, was something I have heard at JFK via LiveATC and flying in South Florida: Controllers shotgunning instructions (often with thick New York accents) to foreign pilots. When the foreign pilots misunderstand or misinterpret the instructions, the controllers’ response is to simply yell the same instruction louder, but with a little helping of extra attitude.

James Shepard

Palm Coast, FL

Tarrance Kramer replies:

The New York controllers are legendary, both for their skill and their attitude. It may seem abrasive from the outside, but they operate the most complex, high-volume airspace in the country. They’re not there to make friends or to be polite; their responsibility is just to safely move thousands of airplanes daily. They’re demanding of the pilots in their airspace. When they encounter one who isn’t keeping up, sometimes they use brute force communications if they’re not getting the message across. As you pointed out, that may involve issuing the instruction again, just louder and more direct.

Speaking from my own experience—admittedly, not in the New York Metroplex—sometimes you’ve got to whip out the parent voice and get stern with someone who’s not doing what you need them to do. I might have a dozen other fires I need to put out, and if a pilot’s not responding correctly, that’s distracting me from my other duties. When standard “controller voice” isn’t working, I am not afraid to throw some attitude to drive the point home: listen up and follow instructions, before things get dangerous.

Back Course Revelation

As a CFII, I found your article on flying a back course localizer approach an excellent description of why the instruments work the way they do. I had struggled with following the needle in the opposite direction of “normal” until a flight instructor shared this practical tidbit with me: “On the front course, fly toward the needle. On the back course, you are the needle.”

Steve Oldroyd

Medford, OR

But, if you’re outbound on the back course, you still fly toward the needle. To determine which way to turn, you have to consider both front and back course, and inbound and outbound.

I’ve been reading IFR for years and love it! The June issue had a great surprise for me. Finally, there is someone else out there who doesn’t believe in “reverse sensing.” When did this term come about? I have an FAA 1980 AC61-27C Instrument Flying Handbook that makes no reference to “reverse sensing.” The current FAA Instrument Flying Handbook does make reference to this miss-interpretation. Therefore, it probably helps propagate the learning problem.

Having an electronics engineering background, I find the notion of “reverse sensing” a disservice to learning to interpret the VOR indicators. It’s not necessary to learn the nitty-gritty phase comparison of the transmitter signals to correctly understand how to read the VOR. I can say that the majority of my new clientele can’t interpret the VOR indications correctly which leads to a lengthy “brain-wash” and reprogramming.

Thank you for breaking this down for the readers. I’m sure there were plenty of readers sitting there cross-eyed as they tried to figure it out.

Larry R. Jarkey

Frederick, MD

Not Flying to Alaska

I probably will not be flying to Alaska anytime in the near future, but I very much enjoyed Jeff Van West’s “End of the Road” article in the May issue. As usual, Jeff’s irreverent and unorthodox but thorough approach to IFR flying is applicable—no matter where we are—as an aid in sweeping the cobwebs out of the corners of our thinking and encouraging us to continue to ask “why is it done this way instead of that?” I believe this is a healthy way to gain confidence and proficiency—and thus safety—in our flying.

Bill Castlen

Dothan, AL

We think so too, Bill. Thanks. As for “irreverent and unorthodox,” well, that’s deliberate too. We think it makes material that can be dull more readable.

We read ‘em all and try to answer most e-mail, but it can take a month or more. Please be sure to include your full name and location. Contact us at [email protected].