ATC is in charge of traffic management, and we’re in charge of getting to our destination alive. When those responsibilities are in conflict, it’s up to us to prioritize.

It may come as a surprise to you that, from time to time, we endanger our lives and that of our passengers, and sometimes even violate FARs, when we accept a clearance from ATC.

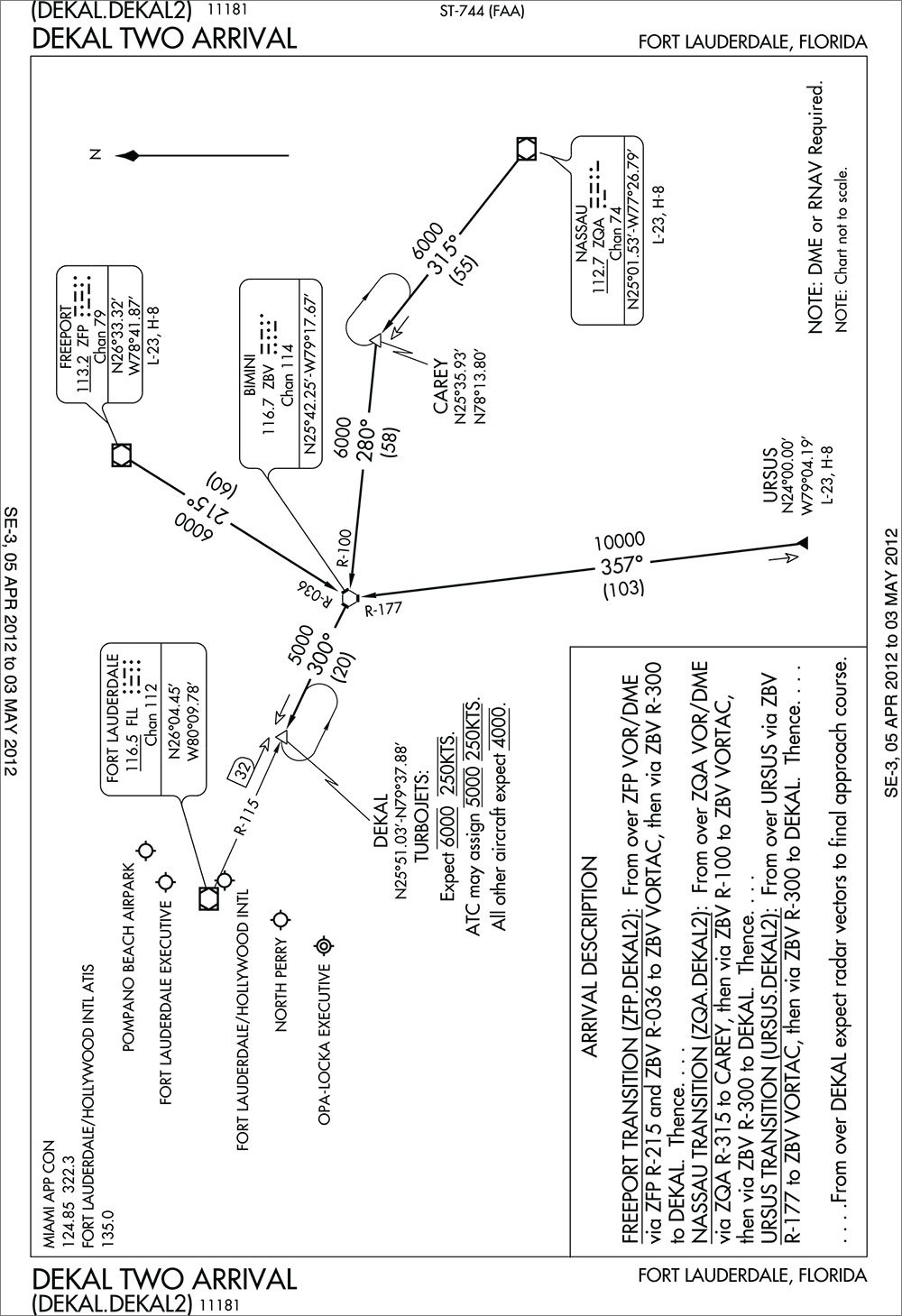

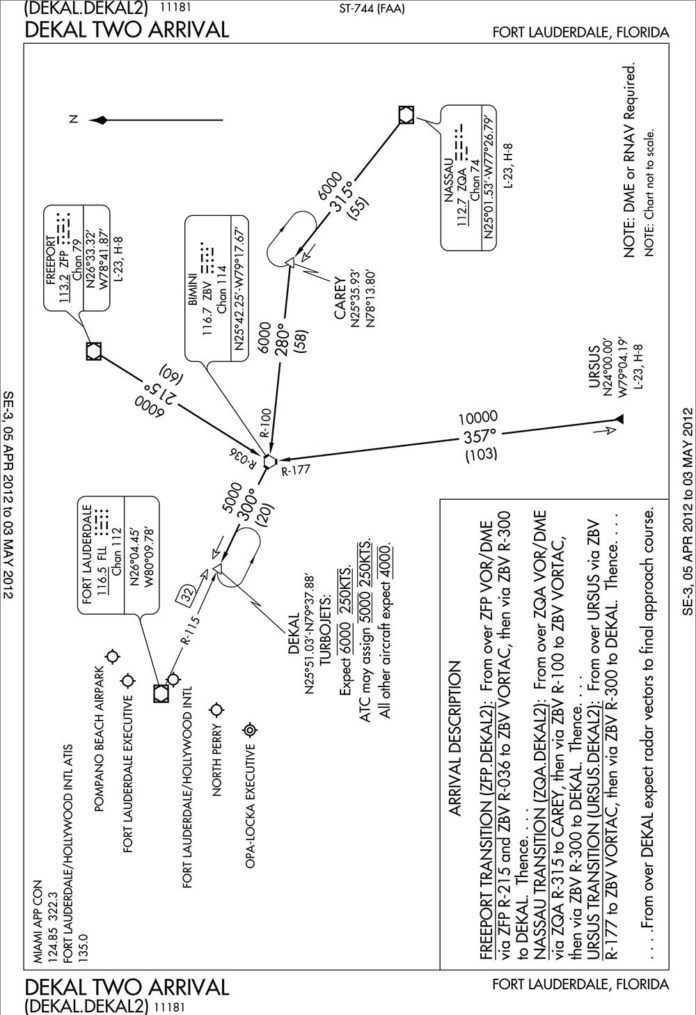

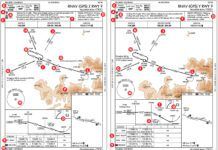

Don’t think so? Take a look at the DEKAL TWO arrival coming into Ft. Lauderdale. This STAR is similar to many other STARs around the country that request you to take excess risk for the sake of ATC convenience—and that’s just for the Part 91 pilot. They actually instruct you to violate an FAR under Part 135.

Legal? Safe?

For the sake of discussion, let’s take a look at a Part 135 pilot’s situation on the DEKAL TWO. He’s flying a Pilatus PC12 or a new TBM 850 between the Bahamas and Ft. Lauderdale along the DEKAL TWO arrival route. Upon reaching DEKAL, he’s instructed by air traffic control to descend to 4000 feet. ATC routinely separates air traffic at DEKAL, putting the slower turboprop aircraft at the lower altitude, while allowing jet traffic to continue at a higher altitude. This is a common ATC technique.

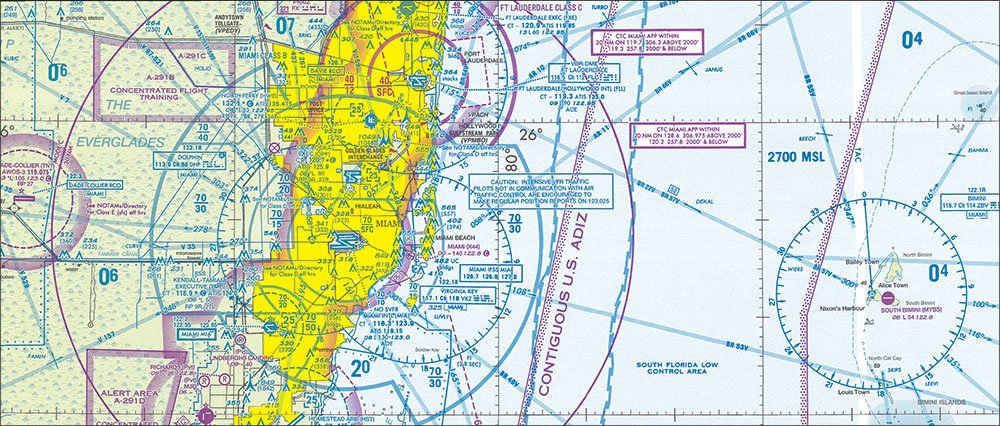

Here comes the zinger: DEKAL is approximately 30 miles from the shoreline.

FAR 135.183 establishes that “no person may operate a land aircraft carrying passengers over water unless (a) It is operated at an altitude that allows it to reach land in the case of engine failure; (b) It is necessary for takeoff or landing; (c) It is a multi-engine aircraft [meeting certain requirement]; or (d) It is a helicopter equipped with helicopter flotation devices.”

Because the aircraft, upon reaching DEKAL, would be operating at an altitude from which it could not reach land if the engine failed, continued operation at the lower altitude would be illegal until that altitude was “necessary for … landing.”

Nothing regulatory stops a Part 91 pilot, but trolling along over water and out of range to shore unnecessarily should certainly give you pause.

But I Am Landing

In all fairness, the FAA has not established a specific definition of “necessary for takeoff or landing” in the regulations. But flying at 4000 feet 30 miles out to sea doesn’t even pass the “sniff test” for “necessary for landing.”

The legal “factual findings” would be based upon whether the assigned altitude is for traffic separation, and whether your aircraft’s performance criteria would require you to be at the assigned altitude at the DEKAL fix, 30 miles from the shoreline for approach into the designated airport.

But, being an attorney by trade, I promise you that if there was an accident, some knowledgeable personal-injury attorney would convince a jury that you didn’t need to be, nor was it prudent and safe to be, at 4000 feet 30 miles away from the shoreline in order to land. For that matter, I don’t think your spouse and children would think so, either. I think that we might all conclude that, whether Part 91 or 135, descent to an altitude below power-off glide distance from shore at the DEKAL waypoint is not necessary.

FAR 91.119 establishes the general minimum safe altitude for Part 91 operations. You will find there similar exceptions in the rule allowing operation below the established minimum altitude when necessary for takeoff or landing. In interpreting 91.119 relating to minimum safe altitudes over congested areas, the FAA noted a longstanding policy on the need for the pilot to “take full advantage of the performance capabilities of his aircraft so as to spend as little time as possible at altitudes below the minimum established for cruising flights.”

You can just take my word for this, or see Legal Interpretations to Frank J. Deighan from Donald Byrne Assistant Chief Counsel (October 30, 1997). That letter stated that “one must determine whether that portion of the flight is necessary to permit the pilot to transition between the surface and the en route or pattern altitude in connection with a takeoff or landing.”

There’s also this FAA interpretation from a request in 2010: http://snipurl.com/23c00o8.

But They Said …

The question here is this: What do you do? Do you do what you are told trusting almighty ATC to assure your arrival? Do you accept the clearance? Do you violate the FAR? Perhaps more importantly, and assuming that you might be operating under Part 91, do you operate in an environment that will cause you to not reach land in an engine-out situation?

I believe that the conclusion is that although pilots must follow ATC instructions, an ATC clearance is not authorization for a pilot to deviate from any rule, regulation, or minimum altitude (see AIM 4-4-1 (a)). A single-engine aircraft, turboprop or not, is not capable of flying DEKAL TWO in compliance with 135.183 or general safety guidance.

The operator would be required to select another route or request a different clearance to maintain an altitude that keeps the aircraft within power-off glide range from shore. And it’s not just an issue at Miami. DEKAL TWO is typical of hundreds of canned STARs prepared primarily for traffic flow.

You are the pilot. You are in charge of flying the plane safely. You are empowered to say, “Unable, it would put me too low over the water.” It may mean a different routing for you. It may mean an annoyed controller. But in the albeit unlikely case your only engine does fail, it may mean the difference between life and death (and giving an unscrupulous attorney access to your estate if passengers shared your misfortune).

But what if you really are landing?

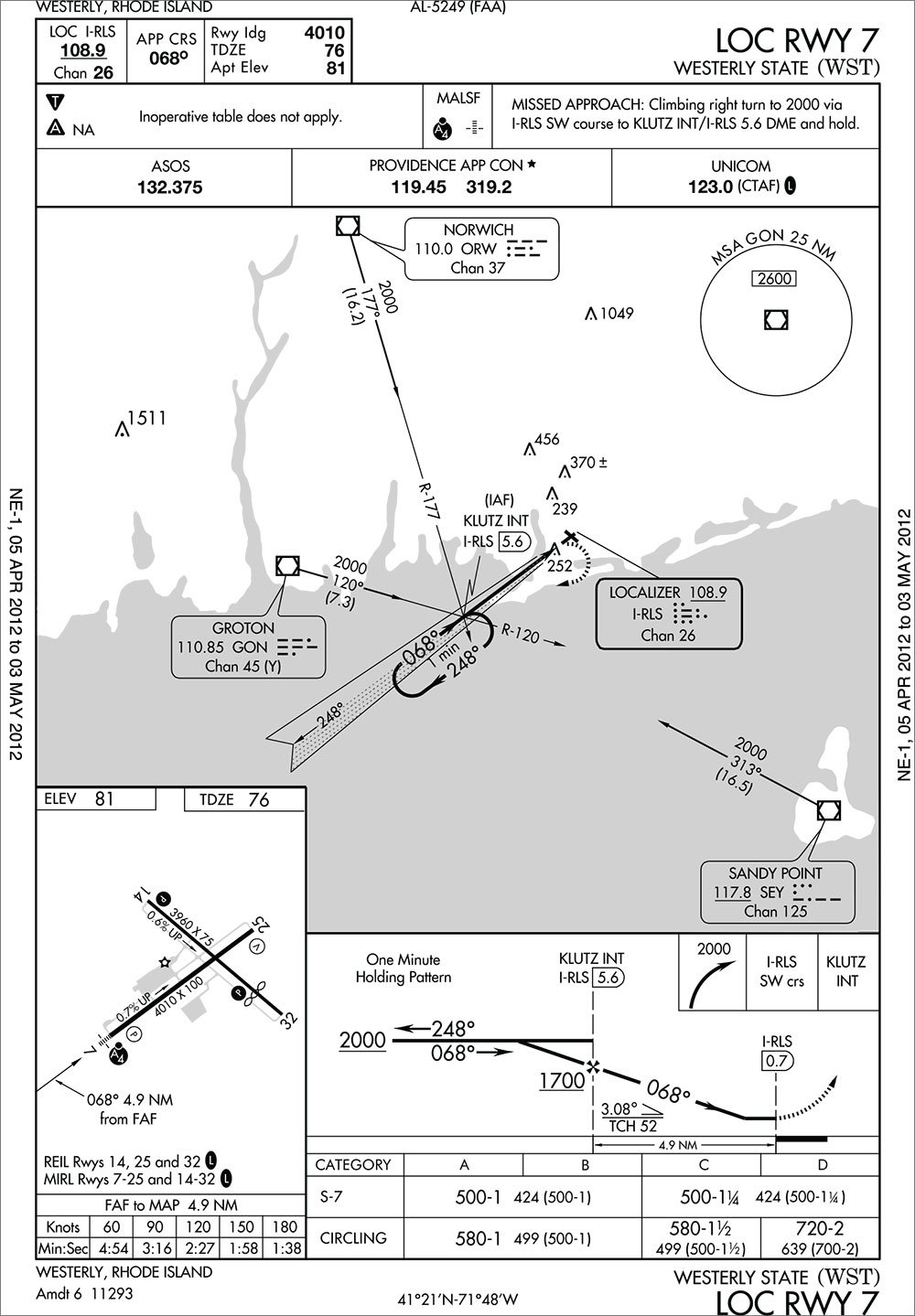

The issue of coming in low over the water takes on a slightly different twist on instrument approaches. Unless ATC mandates something like, “Cross KLUTZ at 1700 …”, it’s an option to just stay high until you’re comfortable coming down. Even if they do issue an altitude, you can negotiate for pilot’s discretion.

But that takes some forethought. Every moment you delay can mean a steeper descent gradient to get low enough for a straight-in landing. When you know an over-water approach is a possibility, check the plate for a published descent gradient between the FAF and a threshold crossing height (3.08 degrees here) or calculate your own. A readout of required vertical speed on a GPS can help, too, letting you delay the drop until a 1000 FPM descent gets you to MDA just before the MAP. —Jeff Van West

Dennis R. Haber is a business and aviation attorney with 44 years of flying experience. He can be reached at www.av8lawyer.com.

I love aviation law articles written by actual lawyers who are also pilots!

Thanks for offering your time and professional experience to the flying community.