Diversions to an alternate, while achievable in an instant by selecting “Direct To” from the “Nearest” list, might not be so quick when facing weather and equipment limitations. Even a pre-planned, filed alternate doesn’t always work out due to unforeseen weather or outages. So finding a new destination on the fly requires some quick decision making. That’s exactly what happens during one leg of this tri-state trip. It’s one thing to divert for hazardous weather; it’s another to push your single-pilot workload right upto the limit when the options get tight.

Plan A, B, C

The trip starts at home base in Erie, Pennsylvania. As plotted, it goes to Lexington, Kentucky, to Clarksburg, West Virginia, and back to KERI. At first, all goes smoothly for you and two passengers in your Cessna Skylane, with sunny skies and a visual approach into Lexington. There, the weather’s perfect for the two-day visit and after lunch, you head out on the Lexington-Clarksburg leg. The terminal forecast there calls for “4SM SHRA OVC025” at your 3 p.m. ETA, followed by a two-hour window of “1SM +TSRA” and lower ceilings. There’s also a Convective SIGMET covering much of West Virginia. But with no sign of weather yet approaching the destination, you get going as soon as possible, knowing there are a dozen airports nearby if the weather develops en route.

You also prefer it to be VFR at KCKB, both for the scenery, and to reduce workload. The two ground-based approaches aren’t available, per the NOTAMs: The CKB and MGW VOR/DMEs are out of service, rendering both the VOR-A and the ILS 21 NA “EXCEPT FOR ACFT EQUIPPED WITH SUITABLE RNAV SYSTEM WITH GPS.” The ILS needs both navaids to identify the initial and missed-approach fixes; the VOR-A requires CKB. And the RNAV approaches to 5 and 23, plus the circling RNAV (GPS)-A, won’t be legal for a legacy, pre-WAAS IFR GPS.

Per the AIM, Chapter 1, Section 2, Required Navigation Performance criteria often precludes the most basic GPS units. These were approved when VOR and NDB approaches with GPS overlays were all the rage. With few of those around now, you’ve relied on a single VOR/LOC receiver with glideslope for ILS approaches, sometimes toggling it over to GPS mode for an en-route backup. This works, but admittedly, it’s not checked regularly for signal quality in preflight as required. And juggling both modes on one CDI has always been a handful, so you’d rather avoid it.

The plan is to file to Clarksburg, then get clearance for a visual. An alternate isn’t required given the decent forecast at KCKB, but by default you find one that’s also forecast to be VFR: KMGW (Morgantown, West Virginia) just 25 miles northeast.

But this plan quickly falls apart when you hear an advisory for “moderate-to-heavy” precip over Clarksburg. From your view 60 miles out, the buildups are indeed forming and the line seems to be marching north-northeast. Perhaps you can set down somewhere and wait it out. What’s around? 4G7? 79D? W22? Unfortunately, getting in VFR requires starting with an IFR clearance to get below the clouds. And, the nearest airports have zero for VOR or localizer approaches, zero weather reporting. Figures.

So, fly north to divert to Morgantown, maybe. You ask ATC for the weather there, and it’ll require an approach with scattered layers down to 700-3 and rain. With the northeast winds and your equipment, the ILS 18 is the only practical approach, with either a circle to land on 36 (hope not) or landing 18 in a 12-knot quartering tailwind (yikes). As soon as you were able to pick up the Clarksburg ASOS, the report’s saying 600 scattered, 1200 scattered with one mile visibility and heavy rain. You’ll have to go south to better weather, or back west.

Divert To the LDA

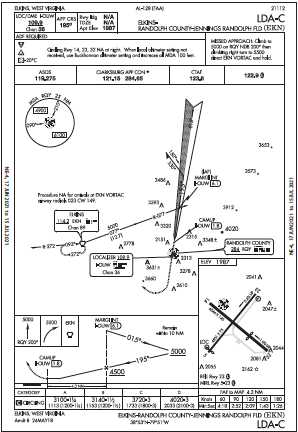

There is a good airport 30 miles to the southeast that’s reporting 2000 overcast and few clouds at 700 feet, plus a more promising visibility of 10 miles in light rain: Elkins, West Virginia. It has two runways, and three RNAV approaches, but of course they all have the “RNP APCH” requirements. So, it’s down to one approach you can fly, an LDA.

Not that you’re experienced with Localizer-Type Directional Aids, but you do know they work like a localizer that’s not aligned a runway. There are perhaps a couple dozen in the U.S. (according to the current edition of the Instrument Procedures Handbook). Some also have glideslopes; most (including Elkins) do not. Most have an offset of greater than 30 degrees and so are circling-only. This LDA is typical, with a 35-degree offset and a cross-radial to identify the final approach fix, a circling MDA and a time table.

The fine print, of course, brings up an equipment check on your part. The missed approach includes a climb “on the RQY NDB 200˚” followed by a right-turn to the EKN VOR. Also, the equipment box says, “ADF Required.” It’s for the missed approach, which is designed to circumnavigate obstacles and terrain on the way to the holding fix. Your GPS does call up RQY and that’s enough to get the job done. Time to escape the weather and request a new clearance. The rain chases you even to Elkins and it’s sprinkling as you break out two miles north of the field at the MDA of 3100 feet, but you can see well enough to fly a standard pattern at 1000 feet AGL to land into the wind on Runway 5.

Different Departure, Too

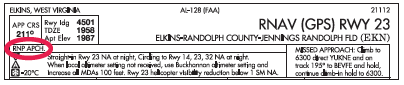

It took a couple hours for the rain to peak and then lighten up, which was ample time to perform a rigorous flight-planning exercise at Elkins for another go at Clarksburg. First, see if an IFR departure is doable with the present conditions of 1800-5 and light rain. Like the arrival, you’re limited in the options. Runways 5, 14, and 32 takeoffs are NA due to obstacles. That leaves Runway 23, which will have a 5-knot tailwind. The departure notes include:

Rwy 23, 1800-2 or std. w/min. climb of 360′ per NM to 4300.

Rwy 23, climb via heading 200° to 5000 then climbing right turn to 6000 direct to EKN VORTAC then EKN R-346, expect RADAR vectors.

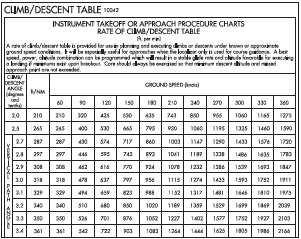

It’s a tad better than 1800-2, but still not ideal. However, you don’t want to wait too long and have the sun start waning for this last leg of the day. The rest of the weather minima bears some confirmation. “Standard” will allow for one SM visibility if you can meet the climb rate from the surface (elevation 1987) to 4300 feet. That’s 2313 feet; if you must depart in a tailwind, the runway’s 4500 feet and with an estimated airborne groundspeed of 90 knots, the climb/descent table has a line for 361 feet per NM, which equates to a reasonable 542 feet per minute.

Still, you’ll feel much better with 10 degrees of flaps and a short-field takeoff at 75 knots to get as much climb performance as practical when entering IMC. You run the numbers and see a 30-percent penalty for the tailwind, but still using 2184 feet, less than half the runway. If conditions are better than 1800-2, you’d want to achieve this anyway as dodging obstacles visually seems just as scary as overflying them unseen. The DP, while more multi-faceted than you usually encounter, is self-explanatory. Fly a heading to the first altitude, continue climbing to the VOR, intercept a radial, reconnect with ATC for a heading.

After a couple of minutes after you launch you’re at 6000 feet, on radar, and pointed back towards Clarksburg, where the latest weather is now calm and 3000-5 in light rain. That’s a welcome break from all that hectic diversion planning while working within the constraints of limited equipment. When the weather wasn’t as threatening, tackling a different kind of approach and flying a dep

So for an example of a “typical” IFR change of plans article, the only option is one of couple dozen LDA approaches in the entire country. Seems contrived to me.

I’d have to agree.

Me too

Great thought exercise! It’s helpful to think though the more complicated examples, practicing the mental processes while relaxed, so maybe the more “typical” scenario one might encounter in the air will seem less complex because of the mental strengthening done on the ground. It’s not the actual scenario that’s valuable – it’s the reinforcement of the neural pathways that we use in decision-making. Great article, thank you!!