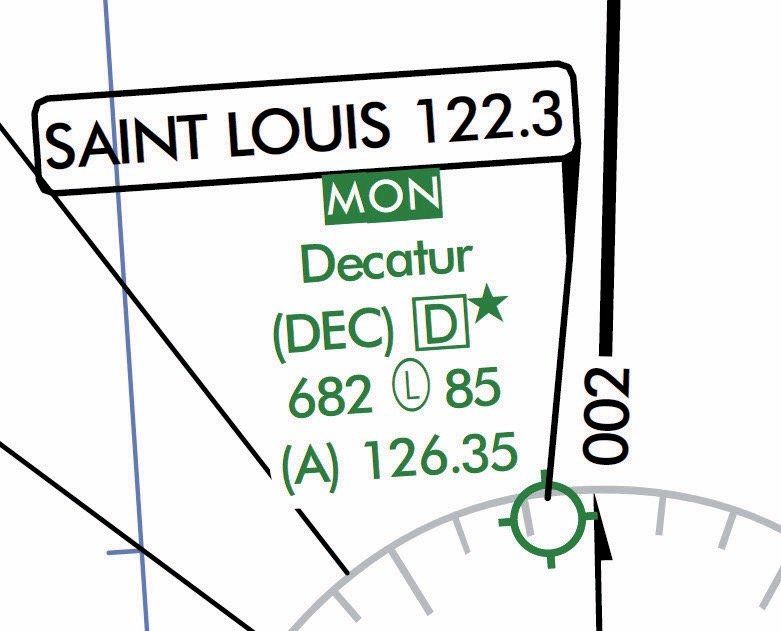

Perhaps you’ve noticed “MON” above certain airports on your low-altitude en-route charts beginning in June 2019. The 200 airports so annotated are specially chosen and sprinkled across the contiguous U.S. (CONUS), identifying them as part of the Minimum Operational Network (MON) of VORs and airports. Those MON airports are also listed in Chart Supplements.

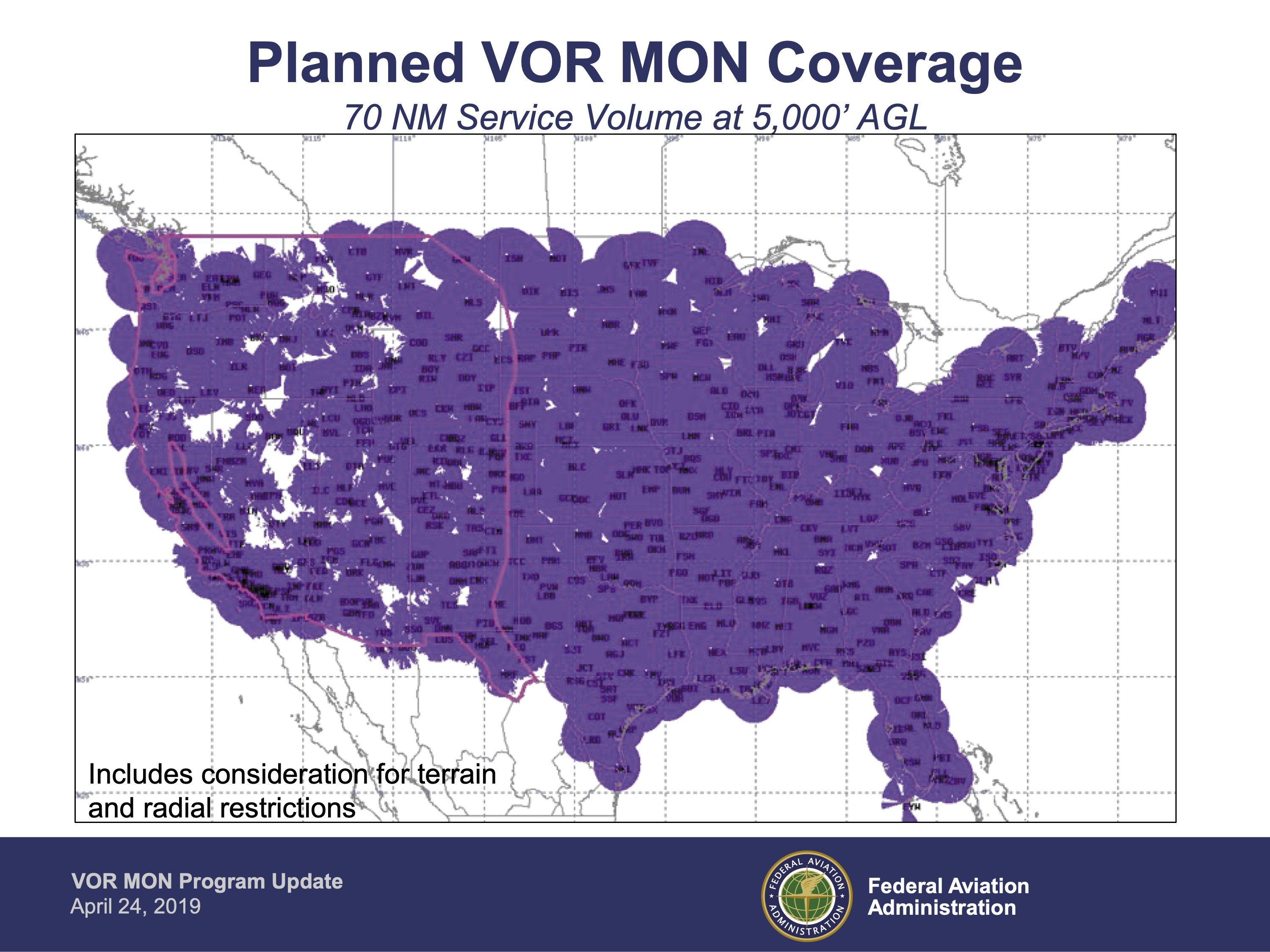

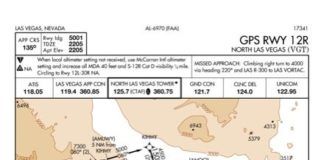

Should GPS go dark, MON airports are planned as IFR safe havens. Each has at least one ILS, LOC, or VOR approach not requiring GPS, DME or, heaven forbid, NDB. A MON airport is rarely more than 100 NM distant. The other part of MON is a downsized VOR network that funnels you to a MON airport from anywhere in the CONUS if you are at or above 5000 feet AGL.

Since its announcement in 2011, the MON architecture has morphed considerably since I first wrote about it in November 2012, “VORs for Armageddon,” again in October 2015, “Your VOR is History,” and most recently, “GPS Backup Strategies” in February 2016. First mention of the MON in the AIM was in early 2017, and the language remains unchanged today.

The MON will pare the current 896 VORs down to 585 by 2025. The 35 percent cut of 311 VORs reflects their growing obsolescence as many, if not most, pilots have now shifted from Victor airway to GPS navigation.

Let’s review the critical points of MON, how to operate in MON conditions, and the VOR discontinuance strategy as they all stand today.

More About MON

In 2011 the FAA announced that, as part of its National Airspace System Efficient Streamlined Services Initiative, the number of conventional navigational aids would decrease as the FAA built more efficient RNAV routes and procedures.

The MON is designed to back up aircraft solely using GPS for RNAV (most of us), should there be a widespread GPS outage. Being IFR, with ATC clearance, you would navigate through the disruption VOR-to-VOR to a MON or other suitable airport.

It’s a little strange that the latest Controller’s Handbook says nothing about the MON. Officially, all we have are the Chart Supplement airport entries, en-route charts, and AIM 1-1-3.f. New AIM and perhaps regulatory guidance would clarify how to use the MON, especially in concert with a minimally aware ATC.

VFR aircraft can fly MON segments as they wish, but the FAA notes that MON navigation will be more circuitous than Victor airways, and Performance-Based Navigation (PBN) routes such as T- and Q- routes.

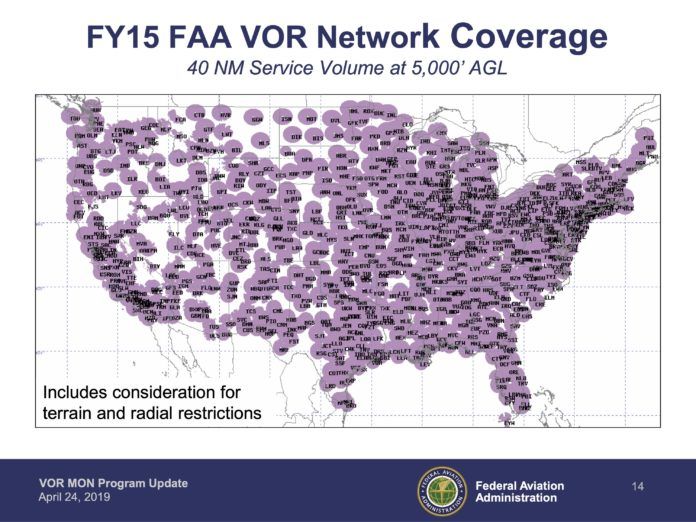

The MON offers nearly continuous VOR coverage outside the Western U.S. Mountainous Area as the coverage map shows. Almost all VORs in that Western U.S. Mountainous Area and outside the CONUS remain as-is. The FAA contemplates no navaid or route structure changes in these areas.

Existing VORs in Alaska will remain. With little legacy gear in Alaska, a recent proposal to the FAA would expand ADS-B coverage by 23 locations to build an ADS-B MON in “the last frontier.”

A New Class of VORs

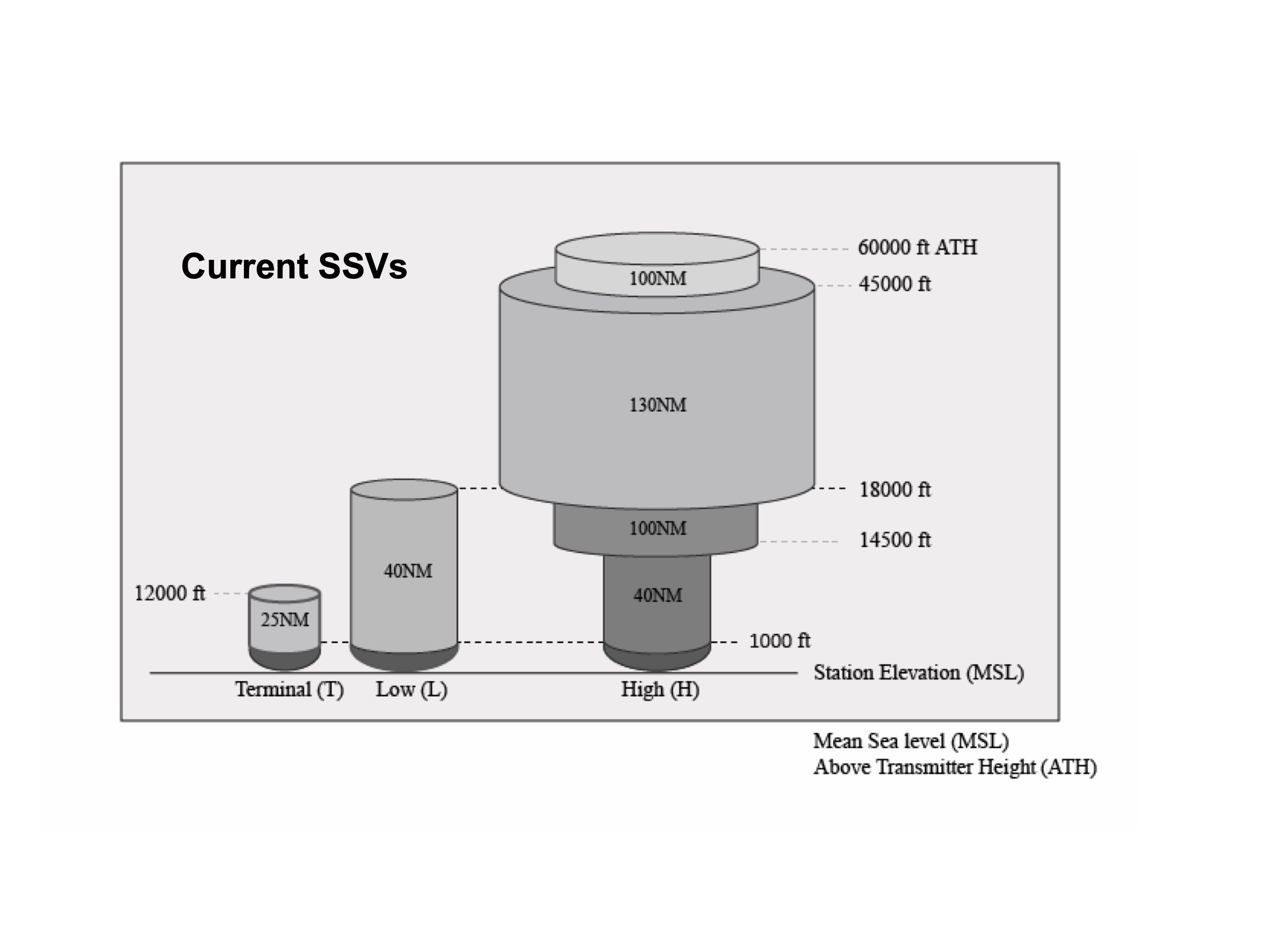

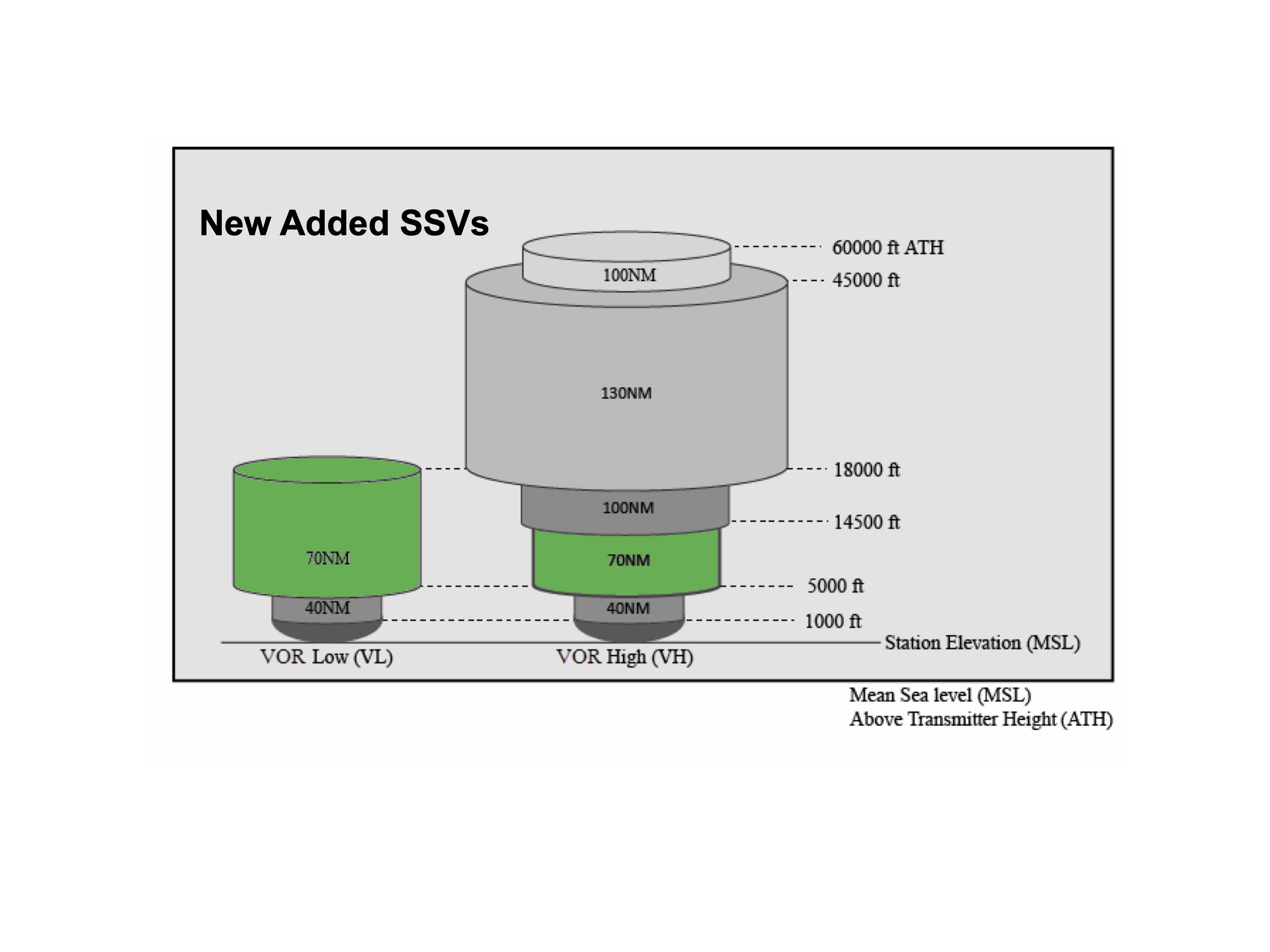

To ensure adequate MON coverage, the FAA developed a new service volume class, as shown above. Adding a service diameter of 70 NM at lower altitudes produces a corresponding service volume improvement beyond legacy Low and High Standard Service Volume classes. The VOR MON makes possible further reductions of ground stations as fewer are required to serve the same area.

DME/VOR/TACAN (DVT)

DVT service continues into the foreseeable future as another viable navigation technology. About 87 percent of VORs were beyond their 30-year useful service lives in 2015. In 2018 the FAA concluded that the DVT infrastructure was not supportable through 2045 without substantial investment in new VORs as mentioned above and new DMEs as explained below.

Civilian pilots frequently use the DME portion of the military Tactical Air Navigation System, which is why DME is available at a VORTAC that combines a VOR with TACAN. Collocated DME and TACAN systems will typically remain in service should the VOR be discontinued.

DME provides slant-range distance information between an aircraft and a DME ground station up to 199 NM away. Common in high-altitude aircraft, DME/DME RNAV is a way to continue via PBN without GPS. Of course, the VOR MON is also available.

The existing 924 DMEs currently support PBN. The FAA will replace 100 with up to 124 new DMEs resulting in about 948 by the end of September 2035, strengthening the DME MON.

Beyond MON

What happens after 2025? After all, it’s just five years away.

For one thing, project date slips are an FAA hallmark. The MON program completion date already slipped five years from 2020 to 2025. Who says it won’t slide again?

The MON will remain until an advanced system emerges that can seamlessly recover from a GPS failure. Until 2014 the FAA advanced a system that provides alternate positioning, navigation, and timing (APNT) as GPS provides PNT. In 2015 APNT research was pushed into NextGen’s far term, 2026-2030. Once the MON is complete, the FAA plans to re-evaluate existing VORs, but at that point, APNT research will just be getting off the ground. The bottom line: some VOR navigation will be with us for years to come. You’d be well advised to keep your VOR navigation skills sharp.

Operate in the MON

Given an unscheduled and sufficiently disruptive GPS outage, expect saturated controllers as they try to assist all affected aircraft. The VOR MON enables pilots to navigate through the interruption into GPS or radar coverage. If widespread, the MON VORs will lead you to a MON airport. If it’s crowded, consider another airport with a ground-based approach or land in visual conditions if able. Be sure to close your flight plan!

Now let’s put this worst-case scenario into perspective. The long-term GPS uptime is virtually 100 percent. Ergo the most likely outage will be local, sporadic, and under five minutes. It’s probably best to do nothing for at least that long to see if it clears. Use the time to perform a local RAIM check if you are not WAAS-equipped. The System Status page in your GPS may show if you are receiving the five satellites required for RAIM or six for the Fault Detection and Exclusion equivalent in WAAS, neither with baro-aiding.

When you report the outage per 91.187, ask ATC if the failure is yours alone. If not, is it local or widespread? Fly your assigned ATC altitude, the MEA, or above the OROCA. As part of the GPS signal, WAAS will be equally affected. The nightmare scenario is the unlikely failure of both ATC and GPS. Then the MON becomes your only salvation.

The FAA does not require pre- or in-flight planning to include diversion for GPS- or WAAS-equipped aircraft to a MON airport. With so few MON airports, filing one as an alternate is probably impractical. Even so, seek the nearest MON airport along your route and check NOTAMs to assure its non-GPS approach is working. Check GPS NOTAMs, too.

WAAS users flying under Part 91 need not carry VOR avionics. Such users are neither able nor required to use the MON. Prudent flight planning should consider the possibility of deliberate GPS outages, as discussed in Jordan Miller’s October 2019 article, “Why GPS Doesn’t Work.”

VORs can’t help unless you maintain proficiency. You’ll be under pressure to get it right. Work in some VOR practice by setting up VOR intersections along your route or find where you are using cross radials. Think of it as contingency planning for a GPS outage.

ADS-B Out is crippled because it uses GPS to inform ATC precisely where you are. However, ATC radar can still see your transponder reply and will know where and how high you are. Similarly, TIS-B traffic service will report radar targets only.

VOR Discontinuation

If you think decommissioning VORs isn’t underway, consider that the ORD VOR at giant Chicago O’Hare airport recently went silent. It’s not even on the en-route chart anymore.

The table below shows the criteria by which FAA VORs get shut down. First deployed in 1946, VORs have grown deep roots. Everyone will be affected.

The next round of thirteen discontinuances is scheduled to conclude by September 30, 2020, ending the 74-VOR Phase 1 discontinuation program. Phase 2 begins the next day and stretches to September 2025, during which a planned 237 VORs will vanish for a total of 311. The 585 remaining VORs will form the VOR MON.

Note that during Phase 2, if the rate of decommissioning is constant, VORs will disappear a bit slower than one a week. You, too, will be affected just as our editor was. (See the article on Page 16.)

When the FAA completely discontinues a VOR such as ORD, they eradicate it from the National Flight Data Center database. It cannot be used afterward as a fix when filing any flight plan. If it anchors any airway segments, those vanish as well. The FAA relocates or reconfigures formerly collocated communication services such as FSS and HIWAS. In some cases, though, the identifier remains for the DME and TACAN sides.

North of the Border

Pilots flying to Canada should know that long-familiar NAVAIDS and routes may no longer exist.

NAV CANADA’s Navaid Modernization Plan intends to decommission VOR and NDB navaids in 15 phases over seven years, replacing them with RNAV routes and approaches. Phase 1 began in April 2019, silencing about 20 NDBs. Phase 2 discontinues 17 NDBs. NAV CANADA will publish Aeronautical Information Circulars for each succeeding phase.

Summary

The MON is a backup system designed for IFR aircraft with GPS RNAV (not inertial or DME/DME) in the event of a widespread GPS outage. Downsized from the obsolescent Victor airway system, the MON is evolving into an operational contingency to back up GPS. It is a temporary transition network until a seamless backup strategy emerges to provide APNT. It also gives users more time to equip with new avionics capable of RNAV and Required Navigational Performance (RNP).

IFR offers $5 in virtual MONopoly MONey to the first CFII who can convince a student that MON means approaches are available only on MONdays. Any takers?

Expert in obsolete technology, Fred Simonds, CFII, still loves those VOR dials with their cute To/From indicators and wobbly needles. He even dabbles with NDBs if he can find an airplane with an ADF receiver that still works.

VOR MON Retention Criteria |

Retain VORs serving ILS, LOC, or VOR approaches supporting MON airports at suitable destinations within 100 NM of any location in the contiguous U.S. |

Selected approaches must not require ADF, DME, Radar, or GPS. |

Retain VORs to provide coverage at and above 5000 feet AGL. |

Retain most VORs in the Western U.S. Mountainous Area, specifically those anchoring Victor airways through high-elevation terrain. |

Retain VORs to support International Oceanic Arrival Routes. |

Retain VORs required for military use. |

Supplemental Criteria |

VORs outside the contiguous U.S. were not considered for discontinuance under the VOR MON Implementation Program. |

Only FAA owned and operated VORs were considered for discontinuance. |

Collocated DME and Tactical Air Navigation (TACAN) systems will generally be retained once VOR service is terminated. |

Collocated communication services such as FSS and HIWAS will be relocated or reconfigured. |

Now, write about SCATANA in relationship with a GPS outage.

Timely article! “Unscheduled” GPS outages are easy to imagine (and therefore anticipate). Some are very uncomfortable to contemplate. Thanks for the thought provoking discussion. I guess I’ll keep the VOR in my panel, and continue periodic VOR approach practice.

That was a very informative, useful article.

Thanks

WAAS users flying under Part 91 need not carry VOR avionics.

Failed to understand the why

“ Such users are neither able nor required to use the MON.”

Dave, if you don’t have VOR, the MON cannot help you. Your GPS will guide you for a time if it can fall back to dead reckoning mode.

WAAS is a standalone system. Backup VOR not required.

Blaine, thanks for the tip on SCATANA. Gotta look into that. Not referenced in any MON material I’ve seen.

Thanks for kind remarks!

~ Fred