A favorite IPC question: “When is an alternate required?” The answer: “Always.” But like most rules, there is an exception. In a style only a bureaucrat can appreciate, the exception is listed before the rule.

Prudent flight planning includes researching alternate airports. A flight might not end as planned for many reasons: mechanical failure, sickness, bladder discomfort, turbulence, enroute or destination weather and destination abnormalities.

A good plan prevents landing to refuel, for example, at an airport without fuel. (Neither the author nor the editor have ever done this.) But, the alternate on your flight plan and a practical alternate are different. Understanding that difference improves the utility of your flying and could save the day.

The Regs

Alternates are addressed starting with fuel in 14 CFR 91.167. It requires enough fuel to fly to the destination, the alternate, and then for 45 minutes at normal cruise speed. The second, 91.169, identifies when an alternate must be included in a flight plan.

An alternate must be filed, and the associated fuel carried, unless the exception applies. If the destination has an FAA-approved instrument approach and the weather between an hour before and after the ETA is at least a 2000-foot ceiling and three statute miles visibility, no alternate is required. This is the ol’ 1-2-3 rule.

There are a couple of gotchas. If your destination has no approach, an alternate is always required. Curiously, though, the alternate need not have an instrument approach if the weather allows a descent from MEA under basic VFR, assuming the airport isn’t otherwise disqualified. Also, both the METAR and the TAF—or area forecast if there’s no TAF—are controlling. So, for flights less than an hour both should be checked.

Not just any airport qualifies as an alternate per 91.169(c). The standard minimum weather requirement for an alternate is 600-2 if there’s a precision approach available and an 800-2 for a non-precision approach. (Note that the visibility requirement is the same. Note also that available means in service with appropriate winds, length, etc., per interpretations of “careless and reckless.”)

These are defaults. Many airports have non-standard minimums for alternate purposes. These are indicated by an on AeroNav charts directing you to look in the “Alternate Mins” section of the approach chart book, and the “For Filing as Alternate” section of Jeppessen 10-9 charts.

Finally, no, your destination cannot also be your required alternate; FAA legal weighed in on that in 2005.

The Details

TERPS say that alternate minimums cannot be lower than the no-light approach minimums, which typically increases required visibility by 1/4 mile. Neither can alternate minimums be lower than circling minimums. The ILS 36 into Napa, California is one such example.

Occasionally an approach can’t be used for alternate planning at all. Airports without weather reporting, or approaches with unmonitored approach equipment, can’t be used as an alternate. Both of these cases also occur at Napa.

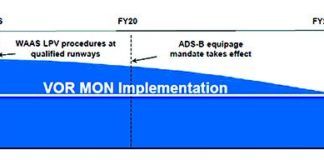

GPS complicates alternate planning. Navigators certified under TSO 129 and 196—most non-WAAS navigators—are supplemental navigation equipment. Supplemental status adds restrictions in that RNAV approaches should be planned at either your destination or alternate, but not at both. Pilots using TSO-145/146 navigators—typically those with WAAS—can plan RNAV approaches for both the destination and alternate. Standard non-precision alternate or non-standard approach-specific minimums still apply.

Practicalities

The rules require you to file an alternate and carry enough fuel. What happens after takeoff is up to you. Your filed alternate disappears into an FSS database and is not sent to your friendly controller. This is the time to take advantage of practical alternates. To do this you’ll need to utilize a couple strategies.

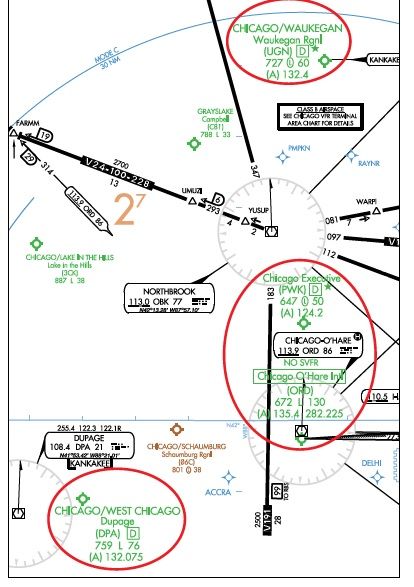

Say you’re flying to Chicago Executive, KPWK. The weather throughout the area is forecast IMC at 700-2, so you need to file an alternate that you almost certainly won’t use. You’re arriving at night, so Waukegan (KUGN, a few miles north) is ruled out because the ILS is NA for alternate use when the tower is closed. DuPage (KDPA), 20 miles away on the other side of O’Hare would be a reasonable choice, but why not just put down O’Hare, only eight miles south?

The weather and proximity make it ideal, although you’d never land there. So, you file KORD as your alternate. As fate would have it, though, when you approach KPWK, the airport is closed due to an earlier accident. So now you have to go to O’Hare, right?

Wrong. You used O’Hare to meet your filing requirements. You’re in the real world now. Just go up to Waukegan, land and call your spouse for a ride.

Fuel is another consideration. IFR fuel requirements are based on flying to the destination, the alternate, and then 45 minutes at normal cruise speed. Cruise speed is much faster than best range or endurance speeds.

There’s about a 20 percent range improvement for a Cessna 172N by slowing from 120 to 90 knots, taking reserve fuel from a 90 nm range to 107. Thus, the alternate you’d actually use could be further away than the filed alternate.

Written decades ago, the regulations assume pilots have little access to real-time weather information. Now, weather information is streamed quickly to cockpits via datalink for near-real-time decision making, allowing more time and many more options.

Of course, you need an eye on the big picture. Areas around population centers offer many airports. As the countryside grows desolate and the mountains higher, airports evaporate. An airport with a single runway, one approach, and no circling minimums in a desolate area should give you pause. FAA legal provided a sober warning in a 2005 interpretation:

A pilot whose aircraft suffers fuel exhaustion prior to reaching either the destination or alternate airport, or who must declare an emergency for an expedited landing (due to low fuel), can be found to have failed to exercise “good judgment,” which could result in a violation of section 91.13, for the careless or reckless operation of the aircraft.

Another nuance is that the regulations cover filing your flight plan with an alternate. You need not identify one later even if the weather goes down. Of course, this is but another example of legal and safe not necessarily being the same.

However, if you didn’t file an alternate and the weather drops to 1500-3, there’s no real likelihood of not being able to get in, so you’d probably be both safe and legal to continue without naming an alternate. Naming one never hurts, though, but be sure you have the fuel.

Putting it All Together

Rules, regulations, procedures, and limitations fill our training. Practical application is often forsaken. When it comes to alternates, legal and practical alternates are two different critters. Identifying and planning for a legal alternate creates a paper trail and ensures you carry adequate fuel.

But, once in the air, a pilot has choices. If it looks like you’re not going to make it in to your destination, slow down to save fuel and start looking at some practical alternatives. Chances are you can find an airport that suits your needs much better than the legal alternate. It might even have a good restaurant to boot.

Terrance Kramer, the magazine’s resident ATC expert, offered some good advice on practical alternate planning. ATC receives only your filed destination, not the alternate. This is why ATC has to ask where a pilot wants to divert. To give ATC a heads up on where you want to go, you can write it in the remarks section, which is transmitted to ATC. Terrance suggests “WX ALT APT – KTMB” for weather alternate airport, Kendall-Tamiami airport as an example.

Jordan Miller believes Wittgenstein’s rule-following paradox applies to 91.167 and 169.

I’ve learned a number of important things through your post. I would also like to mention that there can be situation in which you will have a loan and don’t need a co-signer such as a Government Student Support Loan. However, if you are getting a borrowing arrangement through a common bank or investment company then you need to be able to have a cosigner ready to make it easier for you. The lenders are going to base any decision using a few components but the largest will be your credit score. There are some loan merchants that will furthermore look at your job history and make a decision based on that but in many instances it will depend on your score.