These reports of near midair collisions, NMACs, should be deeply frightening to any pilot. The pilots’ experiences strongly suggest more vigilance and, ultimately, increased safety.

Nose-to-Nose

The pilot briefly looked down to scan the instruments and gauges. When she looked up, there was an airplane right in front of her—she could see faces, wheels … you get the idea. They seemed to be climbing, so she pushed the stick forward and dove. This scared her husband, who was the pilot flying. She cringed, expecting an impact, because she thought they would hit.

This is a prime example of the need to see and avoid, especially as head-on gives you so little time to maneuver. She was scanning while her husband was flying and she looked down for a few seconds, which was long enough to create a deadly hazard.

She concluded, “I can only say how important it is to be diligent and look outside.”

ADS-B Mirroring

ATC advised the pilot of traffic at nine o’clock, two miles, same altitude. He saw traffic on ADS-B but not visually, so he advised ATC. They directed him to climb, which he did though he still did not see the traffic. In a different tone, ATC said, “Stop climb. Descend.” He complied. Then ATC stated, “Stop descent. It appears traffic is breaking away.” He noticed an aircraft on his left wing, about 200 feet away, in a steep descending right turn to pass behind him. He asked ATC to mark the location for an NMAC report.

He knew the other pilot, who narrated his actions by e-mail. “The reason for the rushed ATC instructions came from me. I watched you on ADS-B and opted to climb to increase the separation, but you had the same thought. That was followed by a rapid descent which you mirrored as well. It’s interesting how this incredible technology can lead to unintended consequences.

My takeaway is to make an early heading change rather than altitude whenever possible. If ATC had issued something like ‘BREAK/BREAK Aircraft X IMMEDIATE RIGHT CLIMBING TURN,’ it would have conveyed more urgency. Better yet, ATC should have provided a vector sooner.”

An ATC Save

While the reporting aircraft was on an extended left base turn, the aircraft supposed to follow the reporting traffic behind turned directly toward the reporting aircraft. The horizontal distance between the reporting and other aircraft was about 200 feet on the reporter’s G1000 TIS.

Before the NMAC, the other aircraft’s CFI reported the traffic to follow in sight. When the other aircraft turned toward the reporting aircraft on base, ATC quickly told the other aircraft to return to downwind immediately. ATC’s rapid response precluded the need for evasive action by the reporting aircraft, which would have been difficult in the busy pattern. ATC’s sharp observation prevented the problem from worsening.

ATC Bloopers

Entering the left downwind for Runway 5, the CFI and student spotted an aircraft on the upwind for Runway 28, which crosses into the left downwind for Runway 5. The aircraft’s climb rate would have resulted in a near-midair collision. The CFI took the controls and executed a right 360 turn to avoid the aircraft on a perpendicular collision course. He told the tower they were taking evasive action and gave the details. They landed without incident. The tower never acknowledged the risk of having an aircraft taking off on a crossing runway to their aircraft.

An aircraft called 10 NM northwest and told ATC their intentions. Instructed to report four NM northwest, they complied. Then they were told to fly northeast for separation from a flight of military T-6s to the north on a long straight-in final. They the northeast instruction to avoid crossing aircraft on a southbound straight-in.

The CFI elected to have his student fly north to prevent getting near the approaching aircraft. Outside Class D airspace, he was free to act to ensure safety of flight. They called ATC and informed them they were doing so, unsure of what ATC wanted them to do, as they saw an aircraft 200 feet below rapidly moving toward them on their MFD. ATC insisted there was no traffic to the northwest.

The CFI responded they were incorrect because he had two military T-6s in sight and on his MFD, and they were passing approximately 200 feet below them. They then turned to the left (west trending south/southeast) to keep the T-6s in sight and continued to the airport, surely scratching their heads.

This is a perfect example of exercising PIC authority.

An IPC to Remember

The pilot was under the hood on an instrument currency flight with a safety pilot. After holding, he reported established on the inbound course to an airport for an approach. The safety pilot authorized him to change frequency to the CTAF. Ten miles out, he made an initial call of their location and intention to do a low pass over a runway. Hearing no response, he commented they should be good with no conflicts.

He made a position report at the FAF as he started his descent. He made a final call with their intentions at a waypoint 2.9 miles from the threshold. They still heard no activity, again confirming no conflicts. Then his safety pilot told him to turn left as an aircraft had just departed the runway. He turned left, as did the departing aircraft.

He believed they were on the correct frequency, as he had confirmed it when issued the approval to change to the CTAF frequency. He used a Garmin 225, which identifies frequencies, to transmit locations and intentions. Both pilots recalled the correct frequency was tuned. He used it to obtain the ATIS and for ground communication after landing. He believed the radio was working at the time of the incident.

The other pilot contacted the FBO, where he rented the airplane, and commented that he had made announcements of his intention to depart. But they heard no transmissions.

This sort of thing happens too often, and no one takes ownership. Perhaps the other pilot was on the wrong frequency or had another radio selected. But it’s wrong to assume no one is there if the radio is silent, as the safety pilot knew.

The Problematic Controller

The pilot requested tower clearance to transition west through Class D airspace. ATC approved his request with a midfield crossover restriction. She called small jet traffic two miles south of another airport at 3000 feet.

On this call, she responded with an incorrect call sign. He visually acquired the jet and began a westbound turn and a climb to a higher altitude for his transition, as he believed he was well within the Class D and below the 3000-foot floor of the overlying Class B.

The controller got excited, instructed one aircraft to stop its climb, and made subsequent transmissions to another. He became baffled as to whom her instructions were addressed.

The airspace in the location near his westbound turn is complicated as there’s an overlapping design with different control and altitude jurisdictions. He used GPS navigation and EFB data for a visual presentation of airspace. While it’s possible he penetrated Class B airspace, he said it was “purely unintentional.”

At one point, the tower controller stated, “You almost hit a small jet.” But he had visual contact with the jet that would pass well behind his flight path. The complicated nature of the airspace design, the controller’s tone, and the delivery of his incorrect call sign all contributed to a highly confusing experience. It was not ATC’s best day, nor his, but he kept his all-important cool.

Drones

Of the 50 reports, nine NMACs involve drones. Three advised ATC, but the ASRS reports lack details. The highest altitude of encounter was 15,500 feet. The lowest was 600 feet.

Altitude separation ranged between 500 feet to 100-200 feet and near-zero. In the latter case, a drone appeared directly in front of a pilot doing pattern work. He quickly climbed to miss it.

Horizontal distances are difficult to measure. There was one report at 600 feet and near zero, accounting for the near-miss above. Two encounters were inside Class B airspace. Five occurred on approach or final approach. Three aircraft took evasive action.

Wrap-up

NMAC incidents vary widely, but lack of proper communication or, worse, miscommunication plays a crucial role. Incorrect maneuvering contributes, too. About 40 reports were by general aviation pilots.

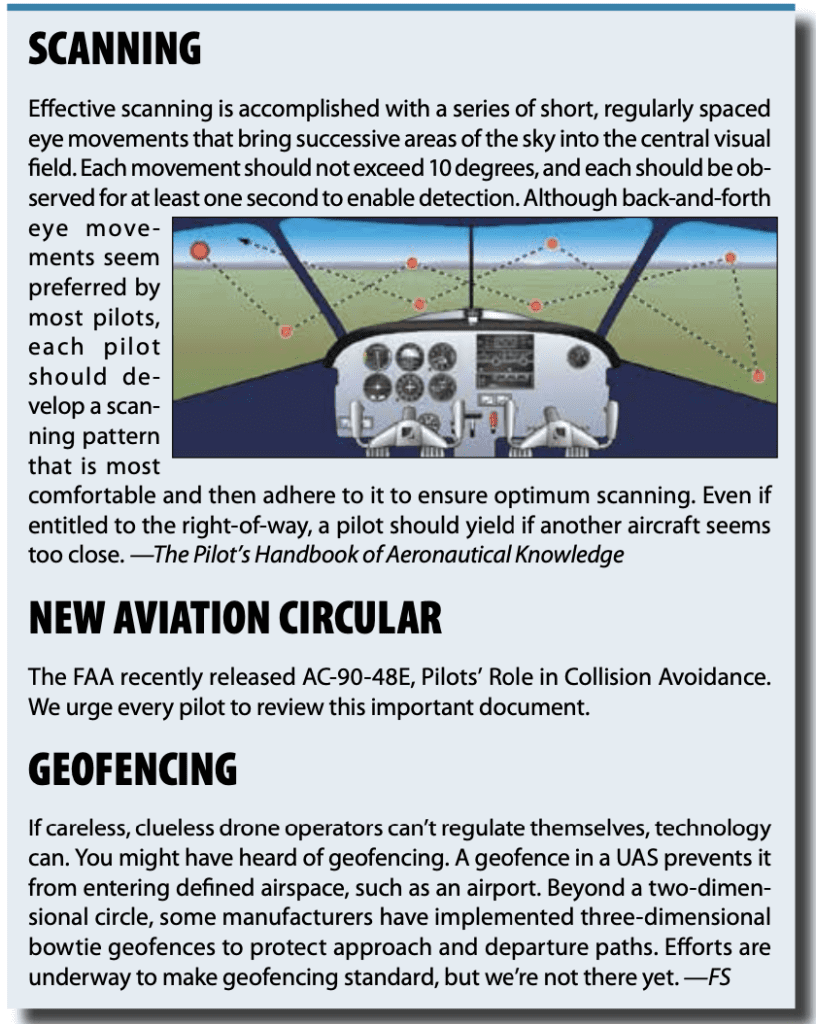

Think before you act. Be up on your scanning techniques. (See sidebar.) Don’t look down for more than a few seconds in VMC. Make “see and avoid” your mantra.

Fred Simonds, CFII, began his flying career with a near-miss, a lesson learned early and forever remembered.