According to 14 CFR 91.173, an IFR flight plan and clearance are only required for flight in controlled airspace, yet most of us have to at least occasionally depart airports within Class G airspace, essentially the only uncontrolled airspace we use. Class G usually ends at 700 or 1200 feet AGL, though there are remote places where it’s all the way up to 14,500 feet. Other than this, there is little guidance in the regulations or elsewhere regarding our responsibilities and protections in Class G airspace, so we have to piece it together ourselves.

Although FAA publications don’t make it clear, we’re on our own for obstruction clearance in Class G airspace. When departing from an airport in Class G airspace, if you’re not following an Obstacle Departure Procedure (ODP), you are not guaranteed separation from anything infrangible. It’s not necessarily unsafe, but it does bear some thought.

ABCs of DPs

Standard Instrument Departures, while offering obstacle clearance, are really there for the convenience of pilots and controllers operating around busy airports. We’ll restrict our discussions to the ODP.

The ODP is purely an obstacle avoidance procedure. They are only required for commercial operators per 14 CFR 91.175(f), though their use is strongly recommended for others. ODPs, while an effective way to remain clear of the rocks and trees, do have limitations.

Only airports that have IAPs are assessed for departure obstacles—if there’s no approach, plan your own departure.

ODPs are designed considering minimum aircraft performance. They’re created for a particular runway when obstacles penetrate the Obstacle Identification Surface (OIS), a plane sloping up from just above the departure end of the runway at 152 feet per nautical mile, .

ODP designers assume aircraft can cross the far end of the runway at 35 AGL and climb at 200 feet per nautical mile, with no turns below 400 AGL. Thus, in theory, you get an additional 48 feet of clearance for every mile from the airport if nothing breaks the OIS.

Note that 200 feet per nautical mile is a climb rate of 200 feet per minute with a 60 knot groundspeed and 400 fpm at 120 knots. This isn’t much, so most aircraft can meet it when performing normally. Of course winds, vertical currents and other sources of decreased performance must be considered, and pilots of multi-engine aircraft must be keenly aware of the impact of a lost engine.

For these reasons you should survey obstructions during preflight planning. An obstruction can require non-standard takeoff minima and climb gradient or an ODP. Knowing where a particular obstruction is lets you stay clear.

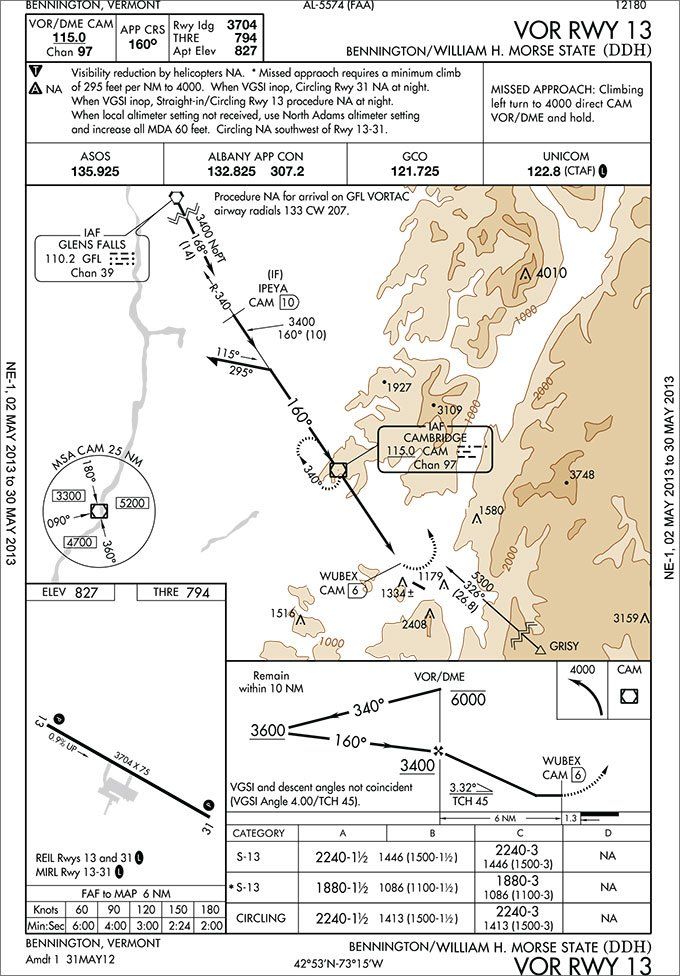

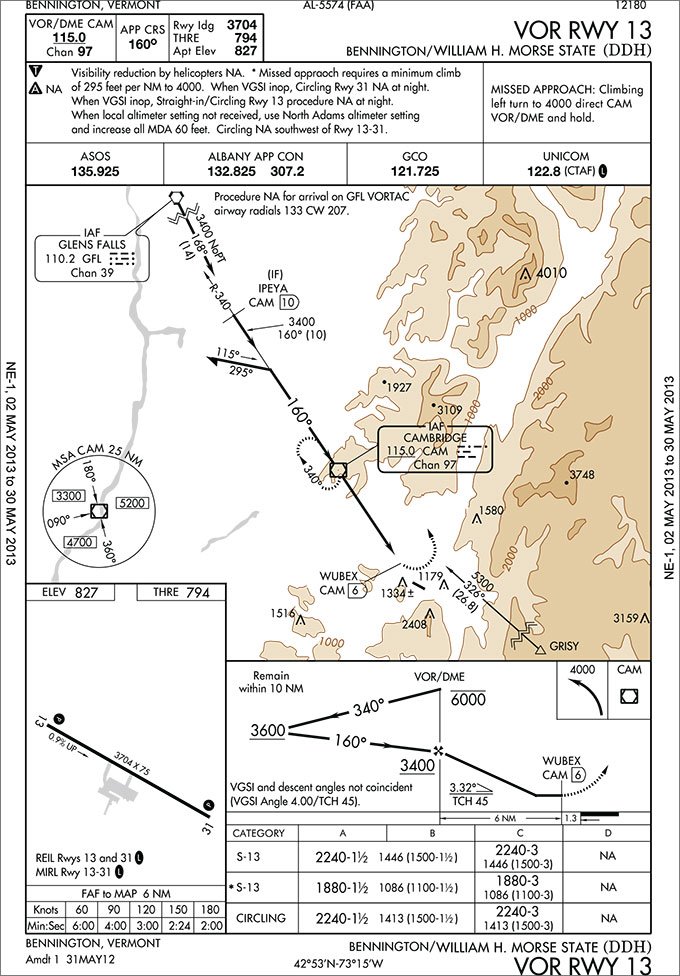

Morse State airport in Bennington, Vermont is in Class G airspace until the Class E starts at 700 AGL—about 1500 MSL at the airport. Notice the towers and terrain north, east and south of the airport. Although the ODP will keep you safe, in Class G airspace you can do what you want, so understanding the obstructions can keep you alive. If the visibility is such that obstructions are obscured, you will need to know which way not to turn, and at what altitude you can turn.

The ODP takes much of the guesswork out of this planning. The non-standard takeoff minima (if you don’t use the ODP) for Runway 13 require 645 feet per nautical mile all the way to 4000. That’s roughly 1300 FPM at a groundspeed of 120 knots—no easy task for most singles and impossible for a twin on one engine, worth considering even though they’re only binding on commercial operators.

What to do without the ODP? A right turn would take you towards the obstruction at 2408 feet. You might be able find your own way mostly along the same path as the ODP as you head to CAM, but you’d need good visibility to avoid the hazards. Perhaps you have performance for a downwind departure on Runway 31. Researching why the non-standard takeoff minima and ODPs are there can help manage the untamed wild of Class G airspace.

When ATC Takes Over

Despite your unregulated IFR departure into Class G airspace, you’ll soon fall under ATC control. You may be asked to “enter controlled airspace” on a particular heading, or fly a heading “upon entering controlled airspace.”

This is more about traffic than terrain. It keeps you out of the way if you lose communications right after launch. This is similar to the “maintain 3000, expect filed altitude after 10 minutes” we receive in a typical IFR clearance.

Even though ATC may give you a heading to fly in controlled airspace, you are not assured of obstacle clearance until you are either on a published route or are receiving guidance in the form of radar vectors. As the AIM says, hearing “radar contact” does not relieve you of your obstacle avoidance responsibilities. Only when you receive a vector does ATC assume that responsibility.

IFR departures don’t seem to get sufficient coverage in basic instrument training. It is understandable that approaches get plenty of attention because of the skills required for the increasingly tight clearances as you near the runway, but IFR departures require the same amount of preparation and thought as arrivals, precisely because there is less guidance and more pilot discretion. Thorough, careful pilots brief an approach fully; you should put as much planning and review into your departures. Beginning your IFR flight in Class G airspace only highlights the importance of this process.

Evan Cushing is a safety manager at a regional airline. In 15 years there, he’s served as pilot, check airman, instructor and fleet manager.