Few situations require quick judgment like deciding to go missed with weather at minimums. Arriving at missed approach point or decision altitude, the pilot must determine if the runway environment is in sight and the required flight visibility is evident. If these conditions are met, is the aircraft in a position to land and is the runway condition suitable? All of this must be accomplished while flying through a sea of obstructions at about 150 feet per second.

If the required conditions are not met, it is time to bug out and fly the missed approach procedure. Decision altitude (DA) on glideslope for precision approaches or the missed approach point (MAP) for non-precision approaches marks the beginning of the missed approach segment. This portion of an approach transitions a pilot from the tight terrain clearances of the final segment to en route margins. Pilots can find themselves outside the safe area by starting the missed approach procedure too late, too low or even too early; in effect, missing the point. Safety can be improved by understanding some of the design parameters of missed approaches.

The Basic Missed

The missed approach segment transitions a pilot from the end of the final segment to a position to shoot another approach or go elsewhere. A typical ILS approach has an 800 foot wide clear area at DA transitioning to 8 miles and a 200 foot clearance height increasing to 1,000. In areas of flat terrain with no airspace conflicts, a straight out procedure to a holding fix accomplishes this nicely.

The increase in height above obstacles is achieved by the standard 200ft/nm climb rate. Missed approaches are designed to clear all obstacles using a 40:1 slope starting from the obstacle clearance height at the MAP. The 40:1 slope equates to about 152 ft/nm, so if you’re climbing at the minimum requisite 200 ft/nm you’re gaining 48 ft/nm over the closest permitted terrain. After a bit under 17 miles, you’re assured of at least 1000 feet above the nearest obstacle—the minimum for non-mountainous areas.

Too Far, Too Low, Too Early

Starting the missed approach procedure at the wrong point can put a pilot outside safety margins. Luck and circumstances may allow a pilot to survive penetrating the boundaries on occasion, but as Earnest Gann says, fate is a hunter. Particularly hazardous, is starting a climb past the MAP or below the MDA.

Missed approaches assume a 200 ft/nm climb starts at the MAP. Therefore, flying past the MAP at MDA results in being below the climb slope. This maverick did a tower fly-by in IMC and ended up filing an ASRS report.

On an ILS approach straight-in, I requested and received clearance for low approach. After reaching an altitude near the DH, with the runway environment not in sight, I continued ahead for a not insignificant distance before executing the missed approach. The localizer needle was not centered (a fact the Tower Controller noticed on radar), indicating that I was probably not still over the runway upon commencing the missed approach climb. It was only after the completion of the flight that I fully appreciated the seriousness of the blunder. The published elevation of the touchdown zone is 173 FT MSL.

The DH is 373. I stopped the approach descent at 400 FT on the altimeter, rounding up the DH in the direction of safety. A look at charted obstacles shows structures on the airport property up to 345 FT MSL (the Control Tower). Not much margin in instrument meteorological conditions.

Fifty-five feet of clearance isn’t a lot considering preflight altimeter checks verify accuracy to within 75 feet. Absolute altitude could be less due to below standard temperatures and decreasing pressure. Starting the climb at the right point would have kept the pilot safer and the controller from spilling his coffee.

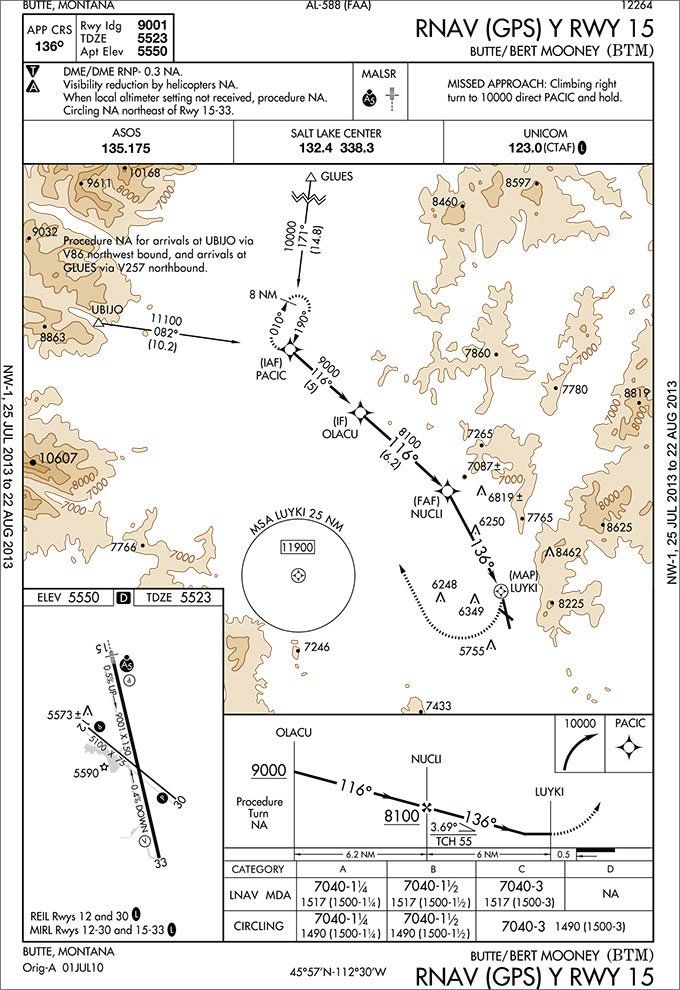

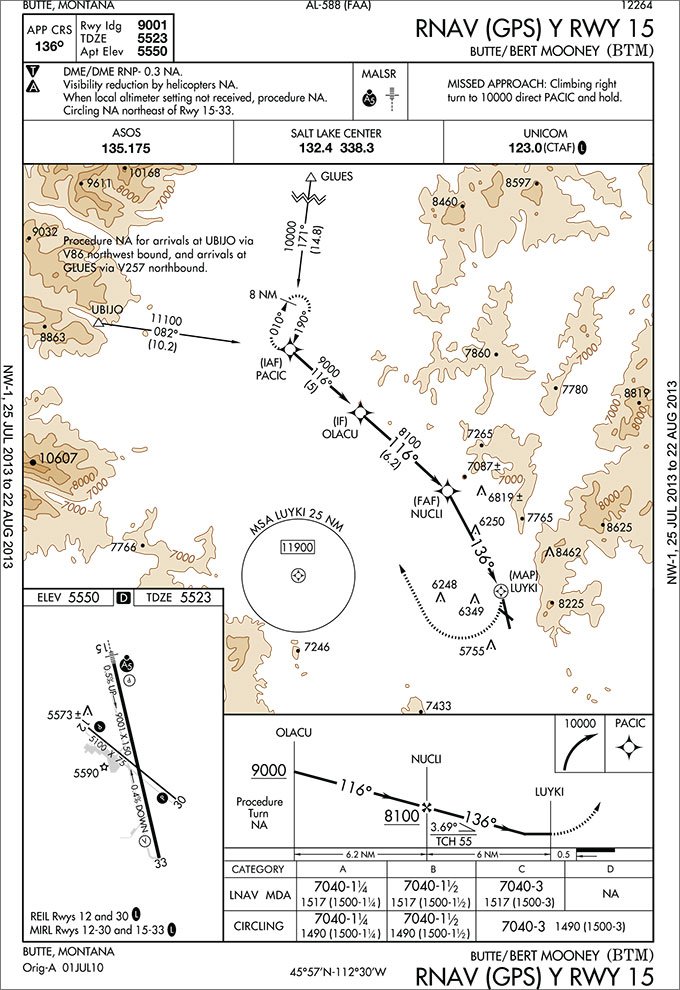

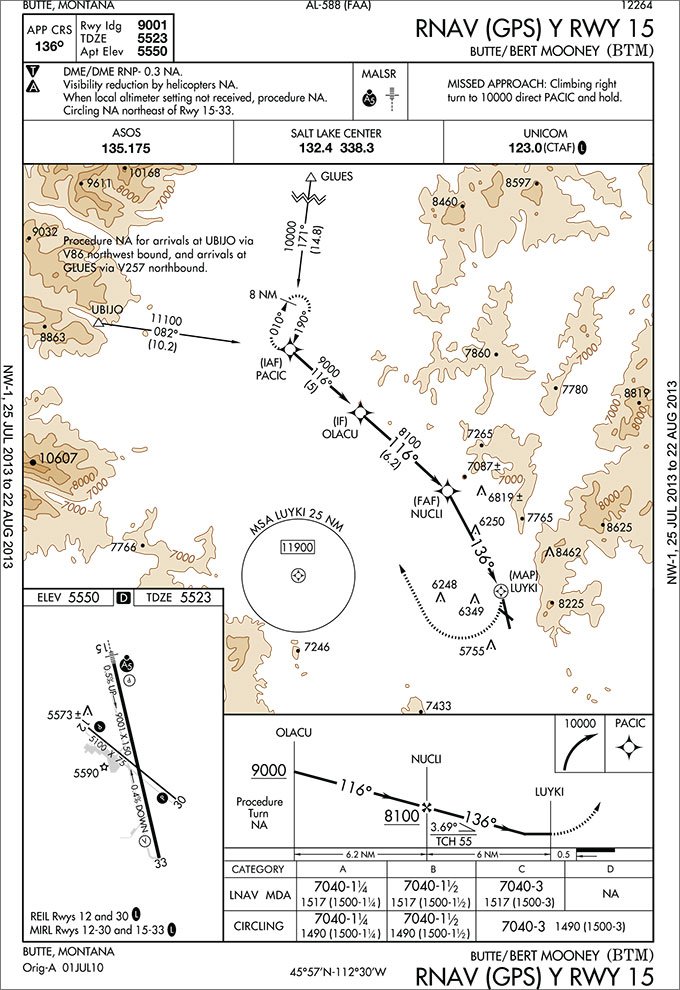

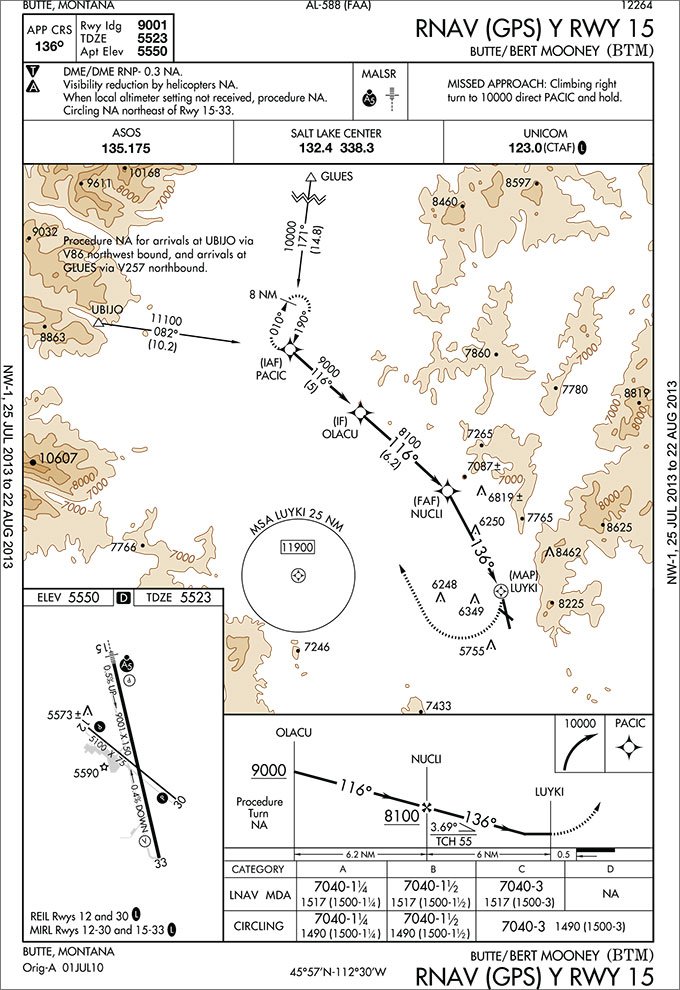

A pilot can get into a precarious situation going missed below the MDA. I recall flying into Butte, Montana on a snowy winter evening. Our bad luck meant the ILS was out of service, leaving us to shoot the RNAV (GPS) Y 15. We saw the runway before reaching the 1,500 foot MDH and were continuing visually. Just before the threshold the wind kicked up. The blowing snow caused a white out that obscured the runway. We were left in a dicey position—1,400ft below the starting altitude for the missed approach gradient, putting safety 1,500ft above since we were also past the MAP. We needed to climb quickly to establish ourselves within the protected area. Fortunately, we had 16,000 pounds of thrust and I believe we used every ounce. Climbing to safety might not be an option for other aircraft, depending on aircraft performance, altitude below MDA, and distance past MAP.

One option for handling being below MDA is to use the obstacle departure procedure (ODP). An ODP starts at 35ft above the runway end, a point below the aircraft instead of above. Refer to the ODP for Butte shown below.

Doing the math, this ODP requires a climb rate of 910 feet/minute at Cessna 172 speeds. The POH for the 172 only shows a climb rate of 575 ft/min at -20⁰C. The 172 can accomplish the normal climb rate for the missed from the MDA, but below it the pilot becomes committed to the landing because the aircraft can’t achieve the required climb performance. For aircraft with better performance, this option puts the starting point below the aircraft instead of well above.

But, a note and a caution are in order. While it might be perfectly safe to miss an approach using the ODP once you’re well below minimums, how many of us would brief the ODP when reviewing the approach? Moral: if you think there’s even a slight possibility of something requiring you to execute a missed approach or abort the landing once you’re below the minimums on the approach, perhaps it’s a good practice to review that ODP.

Turning allows a normal climb gradient on missed approaches with terrain in the departure path. The turns are predicated on starting them at the MAP, so a turn prior to this point puts the pilot outside of the protected area. The correct procedure is to start a climb to the missed approach altitude while continuing on the final segment until the MAP—essentially continuing to follow the proper and surveyed path over the ground, but starting the climb early.

Waiting until the MAP can be a challenge for precision approaches where the MAP is defined by arriving at DA on glideslope. Initiating a climb to the missed altitude takes a pilot off the glideslope. Therefore, timing a precision approach can be a good idea, especially if GPS isn’t available to help identify the MAP.

Putting it All Together

It takes three segments of an approach to get a pilot to the runway yet only one to get away. The missed approach segment transitions the aircraft from the tight terrain clearances of the final segment to en route criteria utilizing a 40:1 gradient. A positive climb must be initiated by the MAP and above the MDA/DA. Being past the MAP and below the MDA/DA puts the aircraft below the planned gradient. An expeditious climb can re-establish the pilot in the safe area. If the climb gradient is well above the pilot when the decision to go missed is made, referencing the ODP is one way of ensuring terrain clearance. Additionally for a miss begun early, no turns should be initiated until reaching the MAP. Arriving at MDA/DA is a decision point, a decision that should be made realizing the assumptions of the missed approach segment.

Same Approach, Different Minimums—Wassupwidat?

Most approaches have the standard minimums. For an ILS that’s 200 feet above the touchdown zone and for a non-precision approach it’s 400 feet above the touchdown zone. Of course, these numbers are just the standard minimums for normal obstacle environments. Numerous factors will cause these minimums to be adjusted upwards. Even if the obstacle clearance is perfectly normal on the approach, though, one of those factors requiring adjustment of the minimums is obstacles on the missed approach.

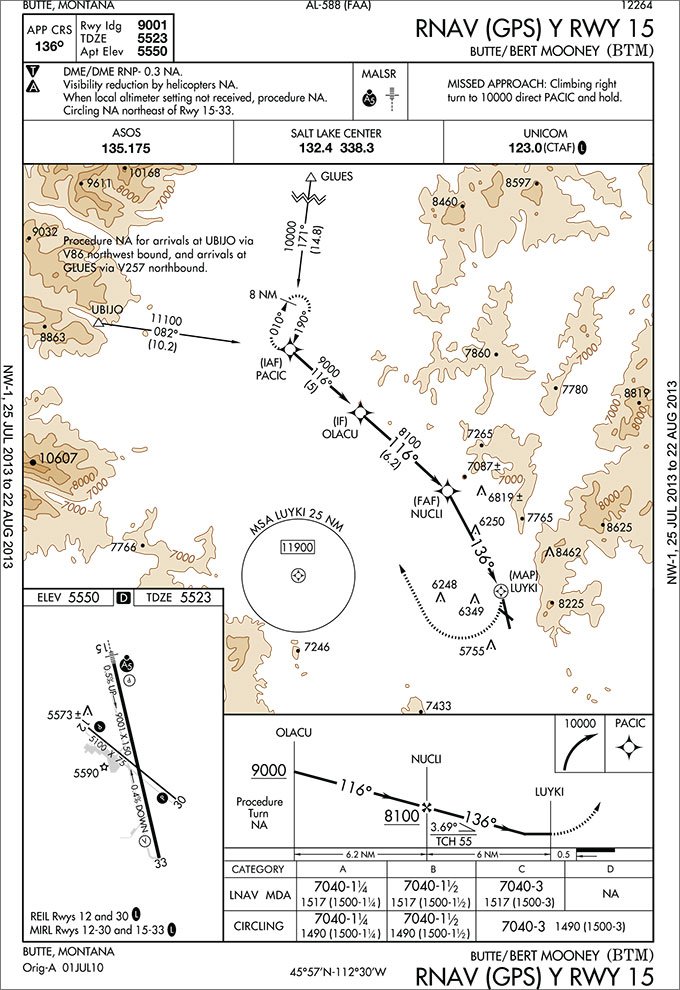

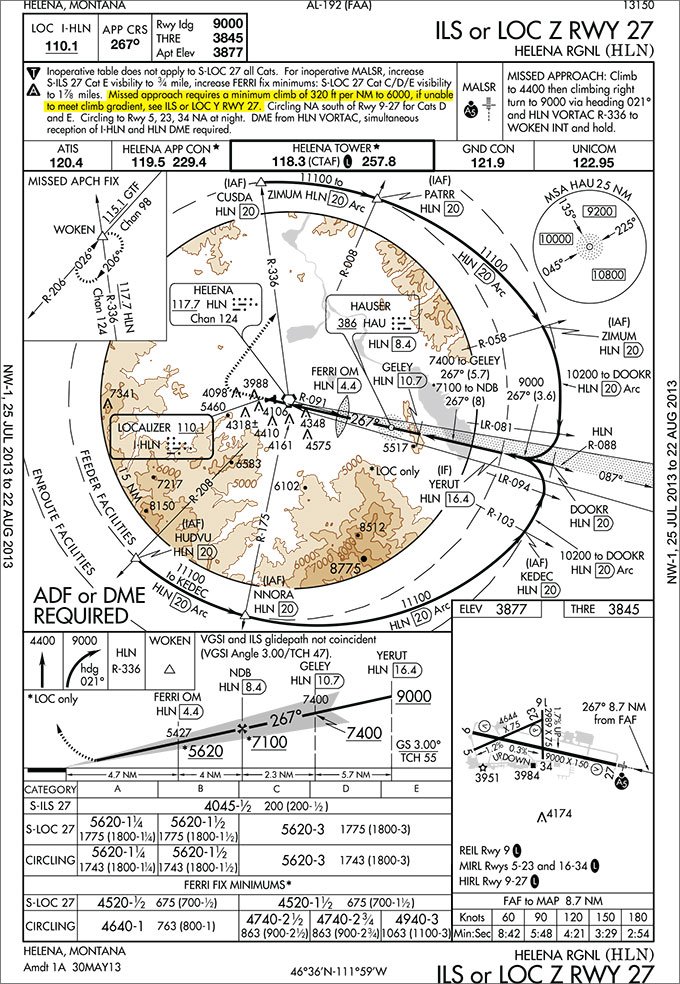

Even with turning and climb-then-turn missed approach procedure segments, on occasion designers simply have no way to create courses without obstacles penetrating the 40:1 missed approach gradient. As a result, designers are forced to raise the minimums—the starting point for the climb gradient—until the obstacles are cleared. This is the case for the ILS or LOC Y 27 into Helena, Montana. The decision height on the ILS is raised to 600 feet AGL to clear obstacles on the missed approach segment.

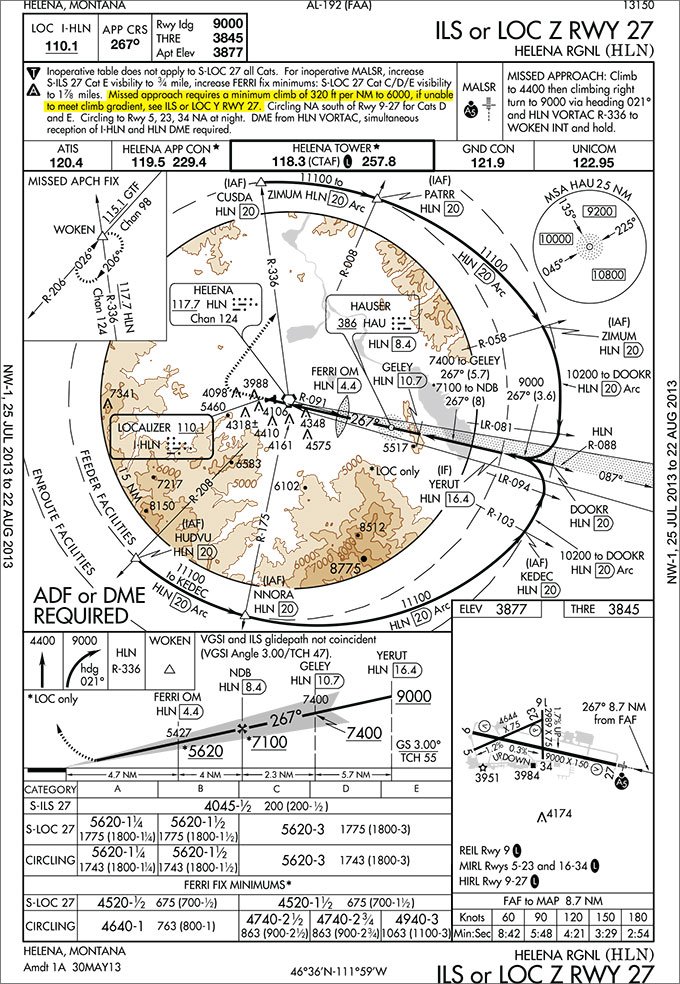

A 200 foot per nautical mile climb rate is a fairly shallow gradient that can be met by most aircraft attempting the approach, and an ILS minimum of 600 above TDZ is rather high. Occasionally when minimums are raised to meet the 40:1 climb gradients, a second approach is designed and published using a higher climb rate. This higher climb gradient for the missed approach allows the designers to publish lower minimums for the same basic approach. The ILS or LOC Z 27 approach uses the standard 200 foot minimums but requires a climb of 320 feet per nautical mile to 6,000 feet.

When there are two charts for the same approach it is important to read the notes and understand the difference. Achieving 320 ft/nm might not be a big deal for something burning jet-A, but is a big deal for a 172 at 6,000. Next time you come across non-standard minimums, see if you can figure out why.

This type of thinking will improve your situational awareness and preparedness for the approach. It might just keep you safe, too. —JM

Jordan Miller, ATP, CFII, MEI would rather not tell you how he came to know the approaches—and challenges—mentioned in this article.