Pandemonium reigned, but it wasn’t our fault. We’d snuck into the super-secret gathering of the Official Office of Plane Safety, which is made up of many of the most highly regarded people in the U.S. who’ve devoted their lives to aviation safety. It was the night when the group would let its collective hair down in a massive exercise in schadenfreude as OOPS would announce the winners of the Stupid Pilot Tricks awards for 2018. Yes, we wore Groucho glasses—but so did everyone else. Members of OOPS go to great lengths to remain anonymous.

Well, maybe some of it was our fault. Everything had been so formal. Magnums of champagne were on every table and tuxedoed bartenders prepared boilermakers and would act as timers for those who wished to see how fast they could down them. There was a raised dais for the selection committee and a fancy podium for the speaker. Above it all was a gold-lettered banner with the motto of OOPS: “If I do this, will I look stupid in the NTSB report?”

When the speaker announced the winner in the category of being stupid while engaged in criminal activity with an airplane, we realized that our favorite didn’t win. Impulsively we yelled, “What about the idiot who stole the twin, landed for gas but saw the cops waiting for him, took off, and then ran the tanks dry?” We’re afraid that our outburst lit the match—more and more attendees started shouting out their favorites.

Politics has nothing on aviation safety devotees whose chosen crash report was ignored. Fisticuffs broke out. Realizing that we were in the category of uninvited guest, we hastened toward the door, only to lose our footing when we stepped on a golden folder. Curious, we picked it up as we got to our feet and raced outside.

Once clear of the building, we examined the folder—it was the holy of holies from OOPS, the winners of the Stupid Pilot Tricks awards for 2018. We opened it and started reading.

What Cell Phones Are For

The pilot departed VFR on a dark night. About two-thirds of the way to his destination he realized that he didn’t know where he was. He circled over a town for nearly an hour but was still disoriented. He called a family member on the ground who used a cell phone tracking app to get the pilot pointed toward the desired destination. The pilot spotted what he thought was the airport, flew the pattern, and completed his prelanding checklist.

All was well until in the flare when he realized that he was landing on a road. The airplane struck trees, veered left and wrapped itself around a light pole. “Missed the airport by thiiisss much.” Well, actually, by six miles.

Lying Windsock

Reading reports of pilots going off the end of a runway on landing is normally so prosaic—the pilot was high, fast, and touched down long rather than go around and set up an approach at 1.3 Vso. Yet occasionally, something adds a little spice and extra foolishness to what would otherwise go unnoticed.

After a Cherokee pilot landed with a five-knot tailwind, went scorching off the end of the runway and became intimate with a culvert, the pilot reported that “the windsock gave faulty information.” The NTSB report noted that the normal landing distance for the airplane under the conditions was 595 feet. The runway was 2355 feet long. Do we need an AD for faulty windsocks?

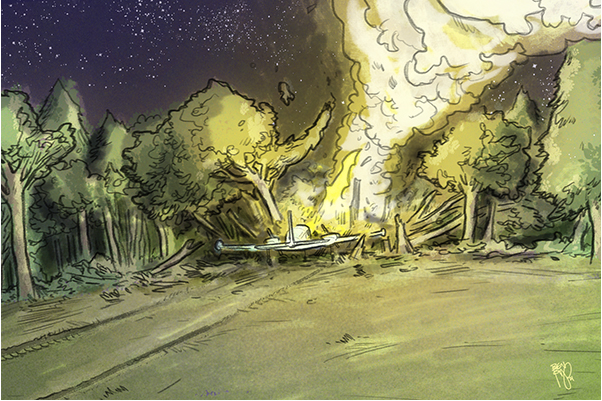

Staying with other-than-prosaic runway overrun adventures, a Cessna 402 pilot decided that he didn’t need a preflight weather briefing but did “check the wind at three local airports.” Despite his wind checks, he said after the post-accident smoke cleared that “he did not trust the wind reports.” Arriving at his destination he set up to land with a 16-knot tailwind—gusting to 27 knots. He went around on two landing approaches before forcing the cabin-class twin onto the ground halfway down the 3000-foot runway. He clamped on the binders, locked up the wheels and skidded off the end of the runway, across an open area and hit trees hard enough to open the fuel tanks and set the airplane on fire. The report did not contain any indication that the airport had a faulty wind sock.

A Cessna 182 engaged in what the NTSB described as “abnormal runway contact” when 20 feet above the ground on final approach, its pilot stopped looking at the runway to focus on the iPad on the seat next to him. “The airplane collided with the ground in a nose-down attitude.” Yes, that fits the definition of abnormal.

Another 182 pilot responded to the need to taxi on loose dirt by using a “fairly aggressive power setting to compensate for the surface conditions.” That wins the understatement-of-the-day award. When making a left turn using his fairly aggressive power setting—and, we suspect, some fairly aggressive brake use—the pilot rocked the airplane onto its right wingtip, then forward until the prop hit the ground. Thinking fast, the pilot reversed the control inputs and put the airplane onto its left wingtip. The NTSB was silent as to whether the pilot then used a hammer on the tail of the airplane to make the damage symmetrical.

A Cherokee pilot making a night flight in mountainous terrain figured that 6500 feet MSL was plenty of altitude. Dealing with some “turbulence and downdrafts,” he “felt a couple of impacts on the left side.” Motoring on toward his destination he heard an ELT transmission on his number two com radio—and it didn’t diminish in intensity. During the landing roll, the left main gear collapsed. While he initially thought that he’d hit a bird, the foliage still jammed in various locations on the left wing was strong evidence that the bird he hit might have been roosting in some trees at the time.

It’s Always Something

During a flight in his Baron, the pilot later reported that the portable GPS fell out of its mount and the antenna cable wrapped around the landing gear handle. The pilot pressed on. Once in the pattern at his destination, he extended the gear. All was well, according to the pilot, until he applied back pressure to flare for landing. At that point the trapped antenna cable moved the gear handle to the “up” position and the aircraft touched down with the gear partially extended.

The solo student in a Piper Lance (Really?!) heard the gear warning horn as he flared to land, so he went around … after the prop hit the runway. He then decided to lower the gear and land on the remaining runway—so he applied forward pressure to the yoke. The airplane touched down, hard, before the gear had time to do its thing. The pilot did not try a second go-around.

An A36 pilot was “distracted by people on the ground” as he approached the runway (“Hey, Buddy, your gear’s up!”) and neglected to extend the Firestones. During landing, he “thought that the propeller contacted the turf,” so he went around. Climbing out, the airspeed didn’t “increase as he felt it should.” Rather than fly around the pattern to a runway, the pilot extended the gear and landed in a field, substantially damaging the airplane.

Launching from a 2738-foot-long runway, the Cardinal pilot got the airplane airborne but reported that the engine lost partial power about 100 feet up. He lowered the nose, which, he reported, restored full power. As he neared the end of the runway, he pitched up again, causing the engine to suffer a “severe” loss of power, so the pilot put the airplane into a field.

Post-accident, the engine ran fine. Engine monitor data revealed that the engine developed full power the entire time. Witnesses to the accident and aftermath said that after the accident they observed the pilot “fill a truck bed with belongings from the accident airplane, including wooden crates full of avocados.” The pilot then admitted that he’d had a “substantial amount” of cargo and had not run a weight and balance before shoving the throttle from quiet to noisy. Shocked we are, shocked.

Stop us if you’ve heard this one before … a pilot takes off to circle a friend’s house … Not going to end well, right? Not terribly interested in the regulation that requires one to keep airplanes at least 500 feet away from people and buildings, the pilot began to orbit the friend’s house at 200 feet AGL. While not exactly legal, all was proceeding apace, and the pilot was undoubtedly getting that good feeling that comes from knowing that people on the ground are certain to be impressed by a low-flying Taylorcraft. Unfortunately, the pilot discovered that during a part of his circle, he was looking into the sun. Rather than begin a climb as his vision was obscured, he started a descent—right into conveniently located power lines.

Abort! Abort! Well, Maybe Not

The pilot of a Cessna 172 admittedly hurried through his preflight—but he really did do a preflight. Sorta. While trundling down the runway on takeoff, he applied backpressure to the yoke to raise the nosewheel and enter full and fearless flight. Nobody home. The pilot then discovered that the control lock was still in place. A mere mortal would have closed the throttle, applied brakes, stopped, and lived with the associated embarrassment unless he could divert the passengers’ attention while he surreptitiously removed the offending device.

The pilot of a Cessna 172 admittedly hurried through his preflight—but he really did do a preflight. Sorta. While trundling down the runway on takeoff, he applied backpressure to the yoke to raise the nosewheel and enter full and fearless flight. Nobody home. The pilot then discovered that the control lock was still in place. A mere mortal would have closed the throttle, applied brakes, stopped, and lived with the associated embarrassment unless he could divert the passengers’ attention while he surreptitiously removed the offending device.

Not our hero—he kept the throttle firewalled while he made repeated efforts to remove the control lock. Meanwhile, the airplane went off the end of the runway, across the overrun, into a body of water, flipped over and sank. Everybody got out. There is no record of the comments subsequently made to the pilot by the three passengers.

We have read with amazement and admiration of World War II Royal Air Force pilots Colin Hodgkinson and Douglas Bader who flew combat—and shot down enemy aircraft—despite having lost both legs in previous aircraft accidents. We note, however, that the aircraft they flew had brakes that were operated by a lever on the stick, not toe brakes.

Accordingly, we must wonder about the thought processes of the pilot wearing an “air cast boot” on one foot when he decided to go flying in one of general aviation’s true hotrods, an Aerostar. Aware that the air cast allowed him to use the rudders, but not the toe brakes, the pilot invited a nonpilot to ride along in the right seat and handle the brakes. The sense of the inevitable is tangible, is it not?

During landing rollout the pilot “asked the passenger to move his feet up to the brake pedals and apply the brakes.” The passenger’s initial input was a bit too strong on the left brake and the airplane “veered left.” The passenger then “applied right brake and rudder to correct,” but the airplane “veered right.” An Aerostar is moving right along when it touches down on landing, so two brake applications are not necessarily going to deplete a lot of energy, although they can certainly cause the airplane to depart the straight and narrow. After the airplane “veered right” it exited the runway onto the adjacent runway safety area, which it traversed with alacrity. Things came to a stop, still on airport property, when the Aerostar ingloriously rolled into a ditch.

A Plan, We Must Have a Plan

Unfortunately, the contents of the golden folder were in disarray when we acquired it and were further jostled as we beat feet from the building—thus, we were unable to discern whether the winners were ranked any further. However, for sheer audacity and press-on determination amidst confusion and an almost total lack of common sense, we admire the Cockpit Resource Management exhibited by a pilot and aircraft owner in a Piper Lance seeking out an airport on a “hazy” day.

Approaching their destination, VFR, they later reported that they “were not able to see the airport environment due to haze, but both of them were able to see the ground.” As children of the magenta line, the duo used GPS to navigate to a point directly above the airport—where they spotted the runway. The pilot made a 180 to align with the runway but could not get the airplane stabilized and went around. He made another 180 to line up with the other end of the runway. Things weren’t entirely stabilized this time either—the airspeed was well north of that published for landing—but the pilot was determined to land the airplane. He did. On the nosewheel. With the airplane exhibiting all of the stability of a wheelbarrow, it promptly turned hard left and exited the runway. The pilot decided to again go around and firewalled the throttle—after all, the airplane still had plenty of speed. The go-around attempt ran into an issue when the airplane rebounded off of a tree, but the pilot kept it going until its energy was arrested by the airport fence.

Following long-term incarceration for mopery with intent to gawk, Rick Durden got to know Editor Bowlin as they each had the same probation officer. Bowlin, desperate for copy for IFR Magazine, convinced Durden to put some words in a row. Durden has been plagiarizing aviation material ever since.

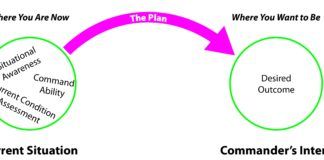

Although, it is very easy to be drawn into the humor of the Stupid Pilot Tricks articles, these stories need to be viewed more as a tragedy, then as a comedy. These stories are being told as HE, HER, THEM or THEY, but they need to be read as I, WE or US. As pilots, we are a small community, and despite having the FAA with ultimate control over our hobby/vocation/profession, etc., we are a product of ourselves. Every one of these folks being lambasted had been trained by a Certified Flight Instructor. They had all passed check rides, most likely given by Designated Pilot Examiners. They had most likely flown with, or watched by, other licensed and more experienced pilots. Yet, despite all interactions with other aviation individuals/professionals, they still made gross errors in procedure, judgement and/or technique.

Was their training substandard? Were they only trained just enough to get past the check ride? Was it stressed to them that just because they now have a license/rating, that it does not mean that they are prepared to fly any airplane into any situation? Were they taught that there is a difference between legal and prudent? Was the principle that a new license/rating is simply a ticket to learn, impressed upon them? Were they taught, that even though flight training is expensive; carelessness, recklessness and ignorance are downright unaffordable? Were they taught that when one person damages or destroys an aircraft, the cost of aviation goes up for everyone?

The following is a quote taken from an Air Force publication, titled “Road to Wings,” which nicely sums up the idea.

“We should all bear one thing in mind when we talk about a troop who rode one in. He called upon the sum of his knowledge and made a judgment. He believed in it so strongly that he knowingly bet his life on it. The fact that he was mistaken in his judgment is a tragedy, not stupidity. Every supervisor and contemporary who ever spoke to him had an opportunity to influence his judgment. So a little bit of all of us goes in with every troop we lose.”

Mark – I had the same unsettling feeling from the first paragraph on and I love comedy. While the humor serves many benefits, it also has its place. Ridicule of fellow pilots would seem to be encouraging practice of at least two of the hazardous pilot attitudes (macho – “aren’t “they” ridiculous”, and invulnerability – “I would never do that”). The aviation community goes to great distances to create a safe, continuous learning environment related to sharing our mistakes (AOPA “There I was…”, NASA forms, etc) and this article’s approach seems to be in direct opposition of the trust and openness that can take decades for a community to build up. The Air Force quote from those who risk the ultimate price sums it up quite well. Thank you for sharing your pov.

I’ve always been told that one can not teach judgement . You either have it or you don’t. Judgement comes from the way the brain processes knowledge and experience.

A+ for use of “Mopery”

I always old young pilots it was not if but when you do something out of the ordinary know what you are doing and if with another tell them to give them a chance to say something. As a helicopter pilot know when to put the spurs in and when to take them out.