One of simulation’s greatest strengths is flying parts of the world where you might never make it in person. Alaska calls to the hearts of many a pilot, so we’ll take you there today. Nothing too strenuous: Just a jaunt from Anchorage (PANC) down south to Seward (PAWD) on the ocean and then over to Kenai (PAEN) on Cook Inlet. Yeah, ICAO Alaskan airports start with a “P” not a “K.” Hmm… if you put the “I”—meaning you—in PANC you get “Panic.” Coincidence?

You might need to install some missing scenery if you excluded Alaska to save space. You’ll also want a plane with IFR GPS for this one. If you don’t have that on your sim, don’t back out now. Use your tablet for GPS location. You’ve probably told yourself you would do that in the event of navigator failure in your airplane. How much practice do you have at actually doing it? Right.

Speaking of practice, a tip of the hat goes to Alaskan pilot Jim Gibertoni who has aviated the Land of the Midnight Sun for over 40 years and is still alive to offer a comment or two about this flight.

Summer in the North

If you can, get real-world weather to just throw some winds in there at altitude. Then set the surface winds out of the southeast at 10. Exact heading is your call. Put bases at 500, tops at 5000, with clear skies or just some cirrus above that. Set the surface temp to about 60 degrees F and the visibility for two miles. Put a non-turbojet airplane at Signature on the south ramp at PANC.

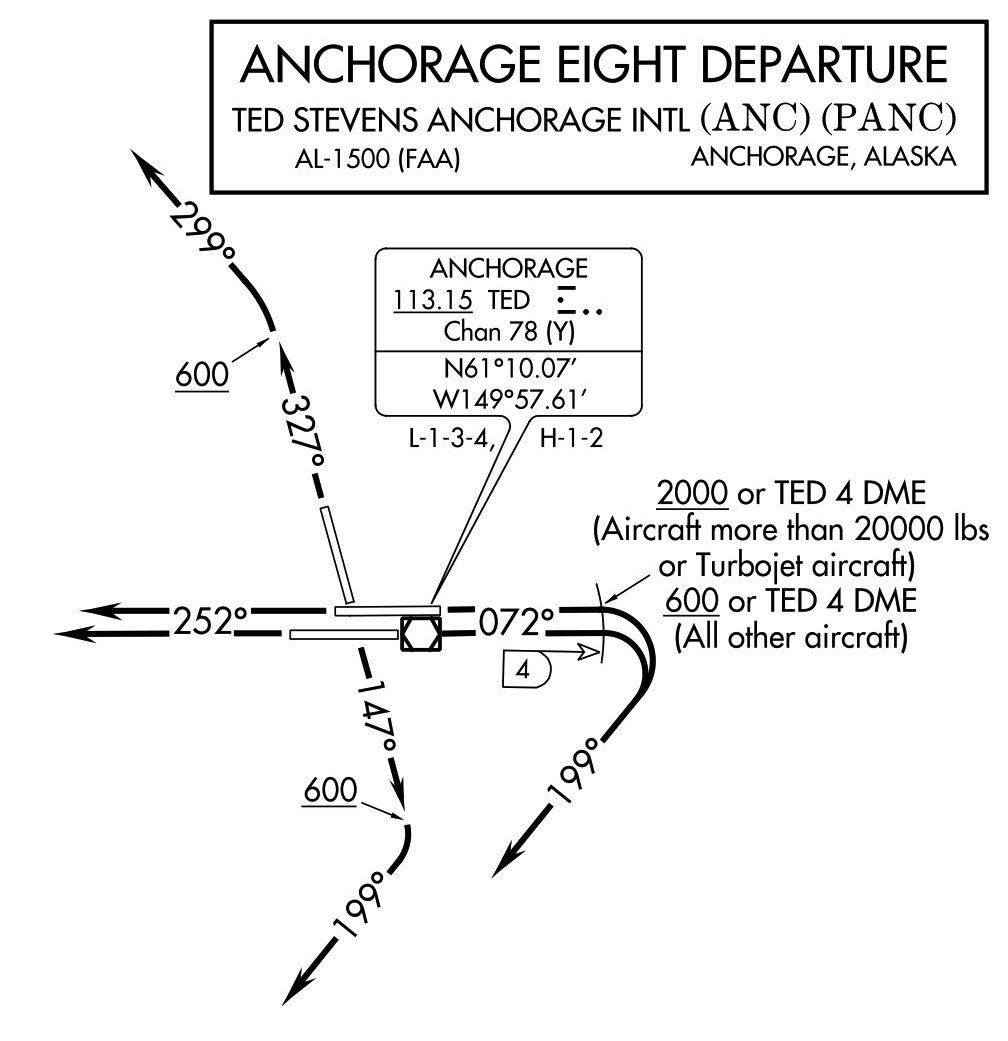

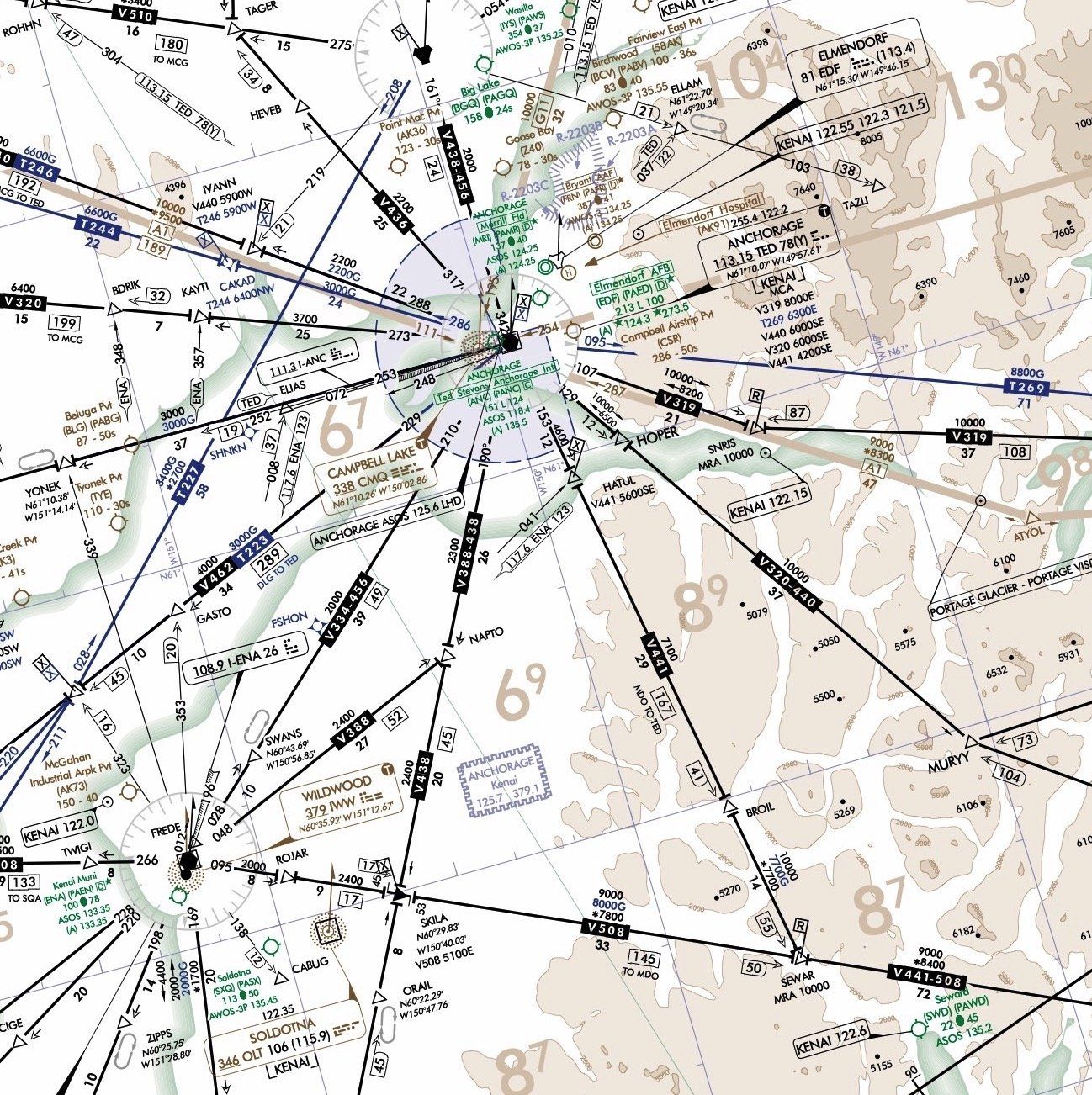

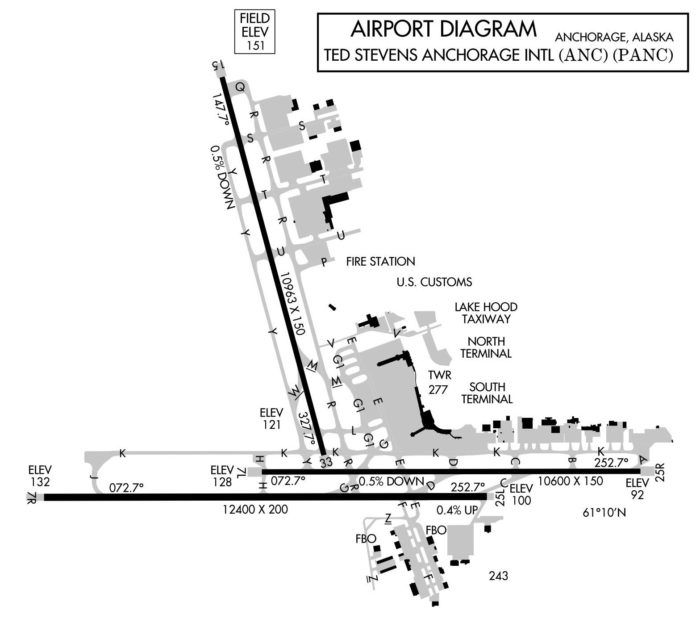

Your clearance is to Seward via the Anchorage Eight departure TED V441 BROIL. Climb via the Anchorage Eight except maintain 9000. If you use a tablet with a profile view, have some fun and load that flight to see the terrain you’ll pass by—and between—in the near future. Your taxi instructions are to Runway 7L. Taxi via Foxtrot, Echo, Kilo, Hotel (welcome to the city closest to Alaska). Cross Runway 7R. Hold short Runway 7L.

When you’re ready, line up on Runway 7L. Assume Tower simply cleared you for takeoff, pour on the coals, and fly the Anchorage Eight. Once you’re established on 199 and passing through 3000 feet, proceed direct HATUL and resume own navigation.

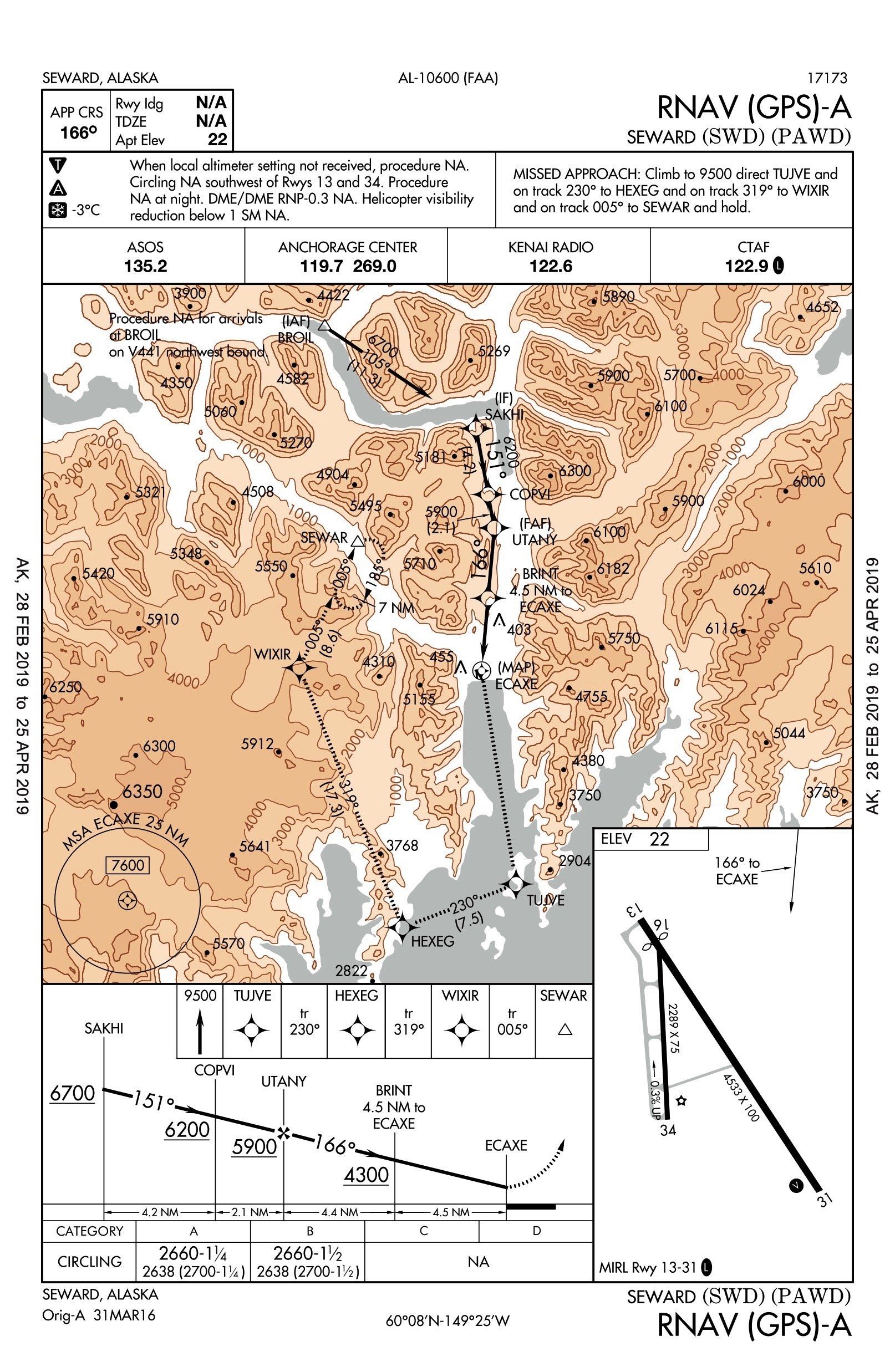

There’s only one approach to Seward: The RNAV (GPS)-A with a jaw-dropping MDA over 2600 feet above the airport. Take a moment to appreciate the amount of brown ink on the chart as you prepare. Study the chart well. You don’t want to fly that missed approach procedure; your new computer will become obsolete before you’re done.

You’re cleared to cross BROIL at or above 9000 and then for the approach. To give yourself a chance, set the ceilings now to 2800 MSL but keep the vis at 2 miles. Fly it to at least two miles before the MAP and then try to land. You choose the runway. Taxi to the ramp.

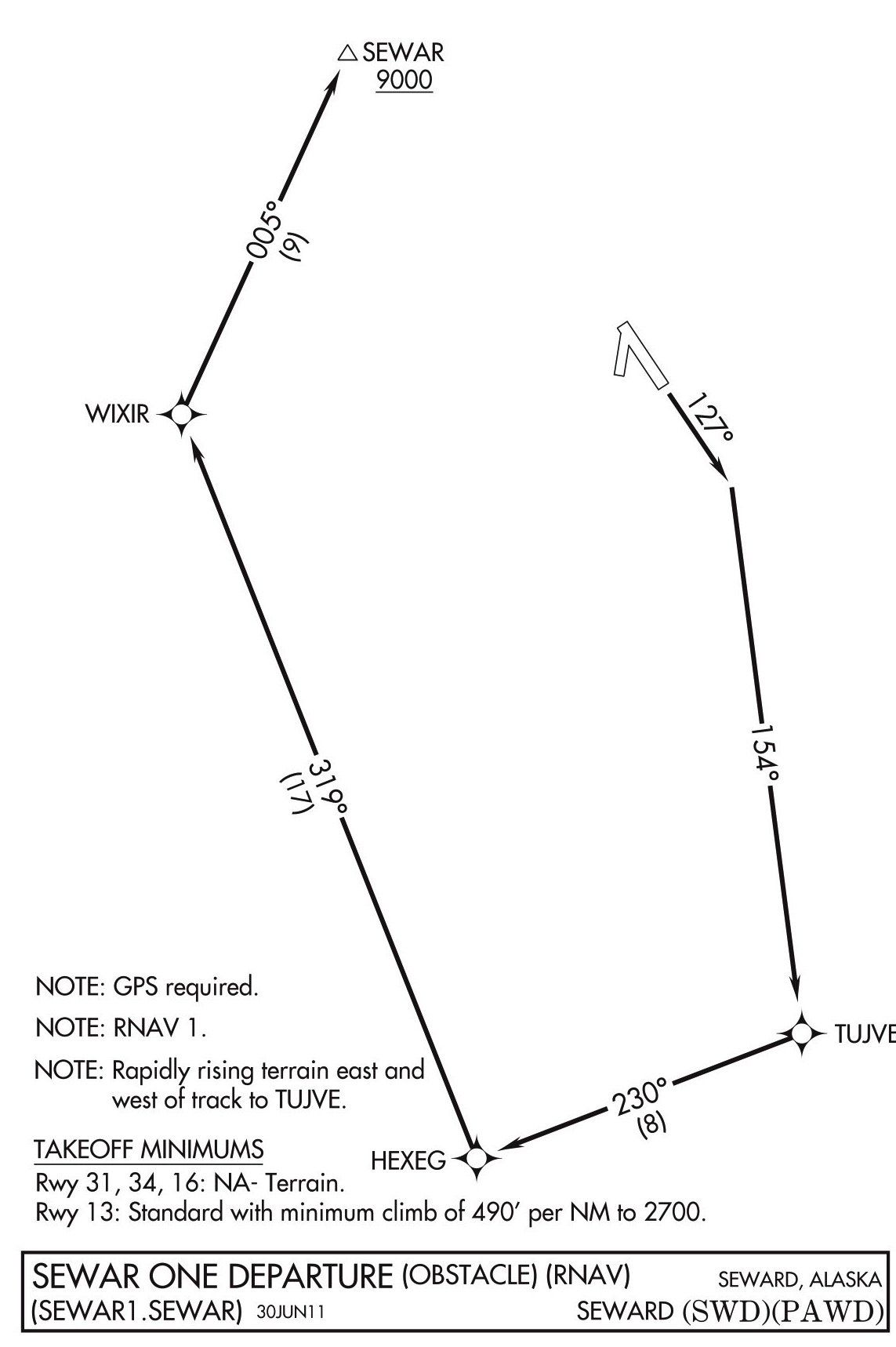

Bring the clouds back down to 400 MSL and set yourself up to head for Kenai via SEWAR One Departure, SEWAR V508 ENA. Climb and maintain 10,000. Departure runway is your choice. Fly the departure and get yourself to SEWAR as efficiently as practical. Oh, and once you’re in the clouds:, fail your attitude indicator. There’s no going back to Seward, so this will be a partial panel flight and approach to Kenai.

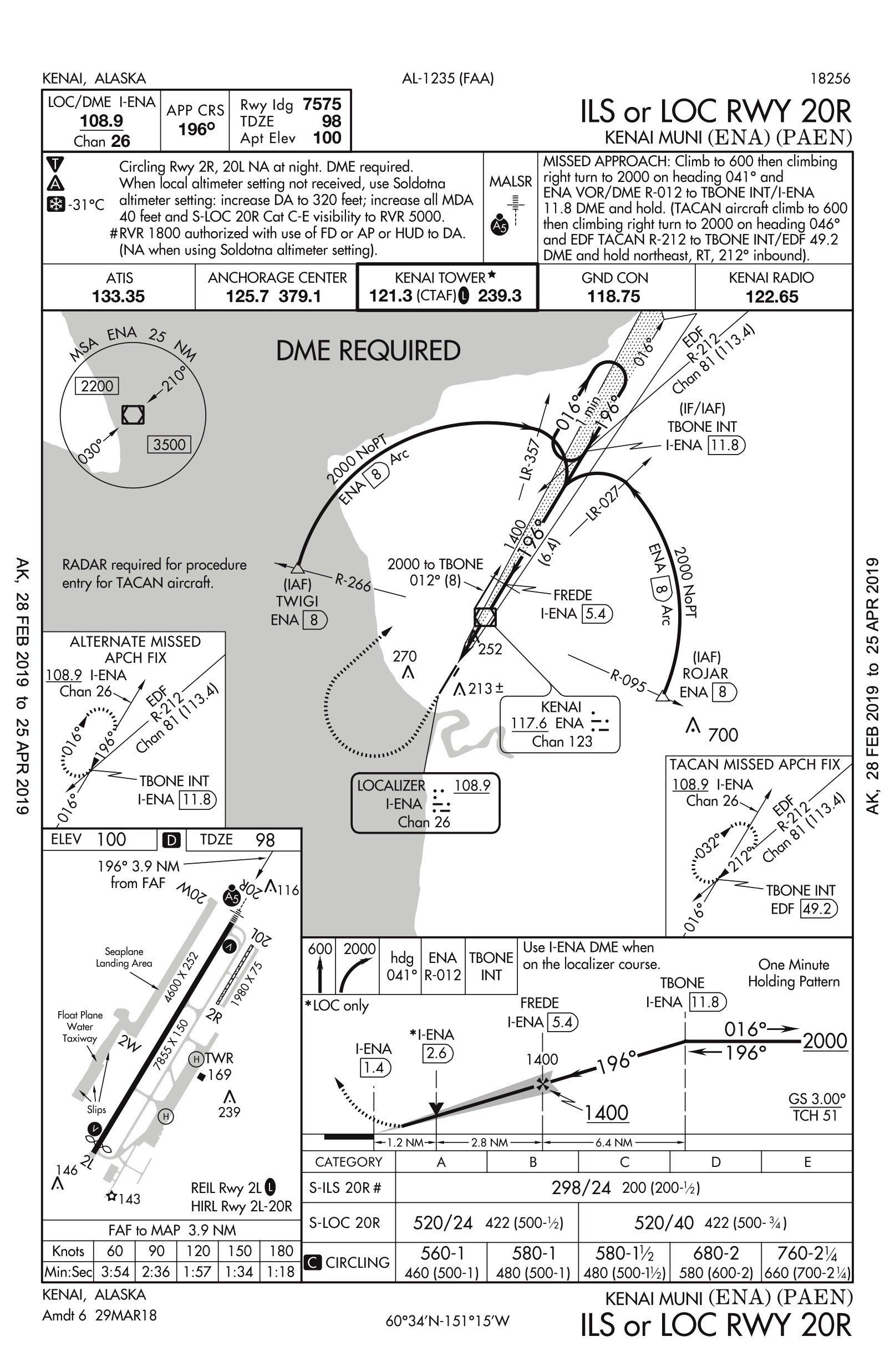

Once you’re 30 miles from ENA, descend and maintain 4000. Runway 20R is in use, so you can either plan the DME arc to the ILS from ROJOR or the RNAV (GPS) Rwy 20R (not shown)from ZUTOR. In fact, pause the sim at 30 miles out and save the situation. That way you can try it both ways. Fly it once with GPS to land, and then once with the DME arc (using GPS or not) and the ILS. Taxi to parking, presuming you didn’t ball it up on one of those approaches.

And if you didn’t, go back one more time to that saved position and throw yourself into an unusual attitude, recover partial panel, and then land.

Questioning Yourself

1. How many “hold shorts” would you expect on that taxi from Signature to Runway 7L?

2. Suppose ATC told you to hold short of the Runway 7L ILS critical area. About where would you stop?

3. Where were you relative to the airport when you turned to heading 199? If you asked for an intersection departure on 7L at E, would it have any effect on your flying of the departure?

4. How many heading changes did you have between BROIL and the MAP? How did you handle the final descent after BRINT?

5. On which runway did you land and how did you get there? What special concerns would you have circling to land in a fiord like this?

6. What’s the frequency for Kenai Radio for? Given those mountains, what’s the chance of reaching Anchorage Center on 119.7 from the ground?

7. How did you set up your avionics for this departure? How did you plan your climbout rate and performance? Can you even leave Seward IFR without RNAV?

8. When did you head direct SEWAR?

9. Which was easier partial panel, the DME arc to the ILS or the RNAV approach? From what altitude did you descend on glidepath/glideslope?

POSSIBLE ANSWERS

1. At least two. ATC can only clear you across one runway at a time and you cross Runway 33 as well. It’s just the approach end, but it counts as a runway in this case. This is a good reminder to study the taxi diagram at an unfamiliar airport before you start driving around. By the way, Jim G. says the gravel runway at Lake Hood is a great alternative to Anchorage if your airplane can handle it.

2. Roughly the intersection of Taxiways Y and K. Jepp airport diagrams are kind enough to show you this top-down. If you’re using government charts, you’ll have to just keep your eyes open for the runway signs. You can also use an aerial view or Google maps to check out the airport paint before you go.

3. You probably turned while still over the runway. The Anchorage Eight says for non-turbojets to turn at 600 feet or 4 DME. Presuming you don’t have a moose tied to the gear, you’ll reach 600 feet long before you get 4 miles from the airport. That’s unless Tower had instructed you otherwise, which they might have, since that turn takes you directly over a parallel runway.

4. Changing headings at the FAF isn’t common, but here’s it’s essential to make any kind of instrument approach, so you’ll change heading three times between the IAF and the MAP. The chart shows BRINT 4.5 miles from the MAP, simply because some databases don’t contain these stepdowns inside the FAFs. Given that you have over 2500 feet to get down from the MAP, you’ll probably want to get down early and have a plan preloaded. Jim draws out his descent plan on paper all the way to the runway for an airport like Seward.

5. We like overflying the airport to descend in left traffic for Runway 13. It’s a steep profile but there’s time, and an open path to abort lies in continuing the left turn to just rejoin that missed—or at least fly over the water. Not only are the rocks an issue, so are the trees. Jim points out that the moment you descend below a treeline of black spruce, the effective visibility drops immensely. Also watch out for low-level VFR (seaplane) traffic.

6. Kenai Radio is there for picking up and cancelling clearances, as well as any other flight services they offer. And you can pick up both them and Anchorage Center as both those frequencies are RCOs.

7. While the GPS will lead you turn-by-turn, this intercept might be easier to visualize by activating the leg of 154 degrees to TUJVE so you see it closing in on the HSI. The departure is the same route as the missed approach procedure, but now requires a climb of 490 feet per NM to 2700 MSL, and only 200 feet per NM after that. So Vy to 2700 and then a cruise climb following to make some distance over the ground would make sense. You could legally depart Seward Part 91 without officially flying the departure…but how?

8. The OROCA is 8700, so if Center could see you, you could get direct SEWAR on reaching that altitude, or even lower if there was a vectoring altitude down there. Wouldn’t count on it in these mountains though.

9. Minimizing changes while partial panel is a strategy for success. The RNAV approach has far fewer changes of heading. Of course, in the real world you’d want vectors to final to make it even easier. The same is true for getting on glidepath. Do it early and higher if possible for maximum time to get stabilized before the needles get sensitive.

True confessions: The author lost it in the final 500 feet of the ILS from the arc while chasing stability all the way from the inbound turn. This was largely due to the aircraft model having a turn-and-bank rather than the turn coordinator he usually uses…and trying to save it on the sim rather than going around to try again.

As Jim says of flying in Alaska: “If you come up here, don’t bring a schedule. It just doesn’t work up here.”

Jeff Van West has yet to fly in Alaska actual, despite invitations. One of these days. One of these days…

We generally do not see SIDS or STARS up here with single engine aircraft. If anything, IFR is generally pretty easy with direct routes. Going IFR into Seward or Valdez, however, is a little sketchy with all the rocks around. I’d definitely advise flying those approaches in clear air before tackling them in IMC.