When traveling via personal piston airplane without so much as a heated prop, we know the drill if there’s airframe ice: Get an immediate route amendment, an altitude change, or both. Escape icing conditions or at least keep the problem from getting worse, then work on a diversion if needed. Just remember that there are trips when this isn’t just a one-time deal…

Two Delays

You and your spouse are en route from the Minneapolis area to Kokomo, Indiana—about 2.7 hours in your four-seater. From KOKK, it’s on to Roxboro, North Carolina (KTDF). There, you’ll overnight with relatives. Tomorrow, add two passengers and fly to the Georgia coastline for vacation, a welcome break from the early winter weather at home.

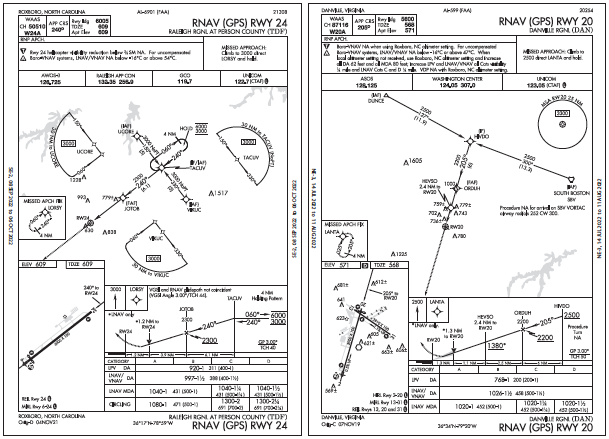

Roxboro’s airport (officially called Raleigh Regional at Person County) has a single 6000-foot runway. With southwest winds and ceilings above 1000 feet in the forecast, plan on the RNAV 24 approach. The filed alternate is KDAN, Danville, Virginia. Everything’s packed and you make a quick departure for Kokomo. It’s an easy leg with full tanks and clear skies, just not as much tailwind as planned. You land just before sunset.

While it’s noticeably warmer than Minneapolis, you don jackets while you’re being fueled. It’s now twilight and getting hard to see. You wonder if there might be frost forming on the wings. You check and, sure enough, it cooled enough to reach the dewpoint of -1 C, which can make any moisture in the air freeze on any surface it touches.

The 15 minutes’ extra flight time left little cushion for landing, topping off and departing for Roxboro before dark. The after-dark takeoff wasn’t a concern as much as picking up frost while parked; the temperatures dropped in a matter of minutes. There’s a light coating of frost on the left wing and just moisture on the right, a sign that the temperature/dew point are hovering right around freezing, making the local distribution of frost on surfaces a bit spotty.

While the textbooks seldom include ground frost, §91.527, “Operating in Icing Conditions” says in your aircraft, takeoff with “frost, ice, or snow” on just about any piece of the airframe is prohibited. An armful of warm towels would remove the light frost while drying the moisture, but frost can return as the surface cools again. Or, a warm hangar will melt frost or light ice quickly, but pulling it out into the cold can start the cycle again.

A clean launch is still possible by starting up ASAP (now) and moving to start airflow around the aircraft. Three of you quickly clean off the surfaces and in a couple of minutes you are taxiing out. It’s still clear and a million at Kokomo and beyond, so you depart VFR and enter IMC at 3500 feet, then resume the climb to 7000. There, the OAT is -6 C. Pitot and cabin heat are working well.

The New Leg

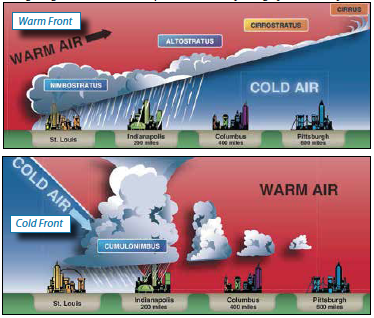

A weak warm front you’ll enter ahead should see the freezing level ascend from 5000 feet to 9000. There’s a related area of overcast layers drifting through southern Ohio and conditions will get cloudy about an hour into the flight to Roxboro. No concerns there as it will be marginal VFR—good to fly an approach and get into VMC a few miles out. There’ll be light rain aloft but still warmer temperatures at cruise—now up to 5 C.

At 7000 feet, you encounter the first clouds, with bases just below you. The analog OAT gauge creeps down to two C. Or is it one? A trace of rime appears on the wings and windshield. Do you descend to 5000, where it’s warmer? Or climb to 9000 for colder? You report the ice and ask about tops. No information in your area, so you take the descent. At 5000 feet, it’s back up to 4 C, just enough to turn the frost back to water.

Fifty miles later, it’s 6 C. The clouds get wetter, and water streaks up the windshield and across the tops of the wings. Suddenly, that water freezes on the windshield.

You’ve never flown into freezing rain, but this might as well be that as it was just a matter of flying into a colder pocket of air. Double-check the pitot heat, ramp up the windshield defroster, request a climb back to 9000 feet. You: “We got really wet in the clouds and now it’s light clear ice.” ATC: “That’s a new one. Climb and maintain 9000 feet.”

More altitude means more options. To your relief, the change puts you on top, so you can breathe and look at Roxboro. Request the RNAV 24 with higher altitudes through UCORE, the northwest IAF. You’ll need more power and speed, and accept a faster descent to get down through the overcast.

Again, Center is helpful and you get direct Danville VOR, direct UCORE. At DAN you’re overhead the alternate, about 23 miles from UCORE, and you switch to Raleigh Approach. They give you pilot’s discretion to 4000. There’s a turboprop single on the same approach ahead of you and already on final, so you don’t expect any delays. Then, ATC tells you that turboprop blew a tire.; now it’s an indefinite delay.

Say Intentions

You request Danville for 5600-foot Runway 20. The diversion starts with a vector north while you regroup. Tomorrow you can fly the 10 minutes to Roxboro and pick up your passengers on time.

But flying the airplane first, you request staying at 7000. Then: “Cleared direct South Boston”—the closest IAF. It’s then over 13 miles for the base leg, at or above 2500 feet. You tell ATC you’ll keep it at least 4500 feet until inbound.

Don’t worry about slowing down either; do that later. You lead the turn well before HIVDO for the inbound and begin descent to 2200 feet to intercept the glidepath at ORDUH. At a groundspeed of 120 knots, you can descend at 433 feet per minute over six miles. Use that time to monitor speed, descent rate and flight controls to ensure the ice isn’t dragging you in. Refrain from using flaps, but then what’s the landing speed?

You use your abnormals training and add 10 knots to the flaps-down approach speed of 70 knots. Keep a touch of power while following the LPV for a stable approach with no changes until the 300-foot displaced threshold. From there, you slowly reduce power and with a gentle flare, roll it onto the runway. Accept the longer landing, but refer to the mid-runway taxiway on the right. All that and you forget to cancel IFR. Center tracks you down at the FBO, more concerned than annoyed, but you explain and thank them for the assistance.

You found out there’s more than one way to pick up ice—three ways, in fact. There’s no shortage of new challenges, each giving you reasons to keep extra tools in the toolbox, including the ones you’ve never used.