Some time ago, I wrote about what happens during an emergency in the tower. But wait. There’s more. Of course, few pilots have declared an emergency, and even fewer have actually had an incident or accident. Crashing an airplane is on nobody’s bucket list (I hope), however the probability of surviving a plane crash varies with the type of crash. If your gear collapses, you’ll probably survive. If you hit something while VFR in IMC, well, you might make the news. For the most part, the FAA has developed some pretty good response actions to assist pilots in need, and not just during an actual no-guano emergency.

Who Ya Gonna Call?

The number of people who find out about your distress starts with the controller you tell. From there it spreads to the whole room, which then spreads to a couple other rooms of people. Depending on location, the resources ATC has in place to assist in an emergency are good. Of course, if you are out in the middle of nowhere and start to have problems it’s best to let ATC know well before hand so they can monitor and send help.

I spoke to a few pilots lately just to ask them questions like, “What would you do if X happens and Y fails?” It was a small crowd, but half the room didn’t even plan to tell ATC. Of that half, 90 percent of them said they would not be on flight following, “just squawking 1200.” They believed their chances were higher by concentrating on flying the airplane and trying to get down safe. Getting down safe is one thing, but what about when you’re on the ground with your airplane in pieces, in hostile weather far from … anything?

Whether pilots believe talking to ATC is important or not is a big deal when handling an emergency that could potentially turn from incident to accident. Altitude can buy you time, but ATC can increase your chances. When a pilot squawks 7700, 7600, or 7500, lots of things happen behind the scenes and people all the way up to DC could learn of your plight. Crash statistics show that someone on the ground knowing what’s happening increases your chance of survival by decreasing response time.

For this discussion, we can say that statistically, the probability that something catastrophic will happen is very low. Nonetheless, anything could happen at any time. Want proof? A wing fell off a Piper Arrow at Daytona Beach a couple years ago. So, yes, “stuff” happens. Despite that sad day, ATC and other aircraft provided a quick location for authorities.

First Response

The first thing ATC listens for is the magic words “declare” or “emergency,” or even an ELT in some cases. Of course, I’ve also heard expletive-laced exclamations that were sufficiently informative that I declared for them. The controller in charge (CIC) and other controllers in the room are generally notified by the controller shouting, “I’ve got an emergency!” This normally ceases non-relevant conversation. The controller working can’t just stop everyone in the air, so he or she starts to move everyone out of the way and continues working the emergency, asking for fuel and souls on board, etc. Any information a pilot could pass is useful.

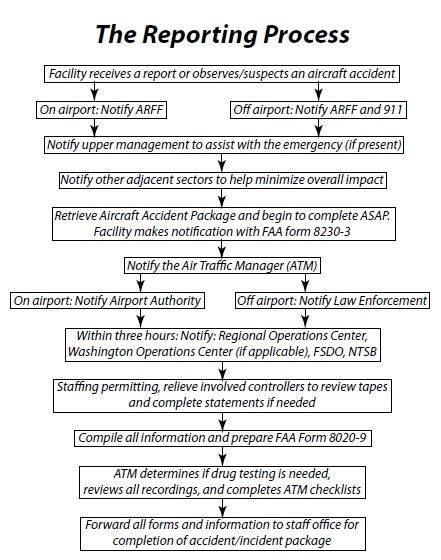

Someone in the facility is responsible for the crash phone and will gather information and “rolls the trucks” as soon as practical. The CIC then notifies management, whether they are in the building or at home, and calls for any assistance needed from other controllers on break or otherwise occupied. Adjacent facilities (including approach control) are notified by the first controller to get to it. It’s a team effort, and emergencies are time critical. Better that two people call than someone thinking “I thought the other controller called people.” The CIC then breaks out all the forms potentially needed and starts filling ’em out.

Now assuming all goes well and the aircraft lands safely, this process slows way down. A “non-event” is an emergency that has a good outcome (aircraft lands safely and no one is hurt and nothing is damaged). We still have paperwork to do, but not nearly as much as a worst-case scenario.

Once an emergency starts, the controllers working are generally not relieved until the event is over. However (if staffing permits) another controller will come to monitor the position. It’s great to have a second pair of eyes in a higher-workload, higher-stress environment. If an accident does occur, controllers can be held for drug testing and removed from their position for a certain time. This is not disciplinary; it’s just standard procedure.

In an emergency, they say that seconds could mean the difference between life and death. It doesn’t matter if it’s an airplane crash or just a bicycle crash. The logic is that the sooner help arrives, the higher are the chances of surviving any accident. Think of the Titanic for example…

I was talking to a buddy from a facility in Louisiana a while back, and we started talking about a Cessna that had crashed. He wasn’t working that day, but he told me what happened. A Cessna was on VFR Flight Following passing from west to east at 3500 feet. In most cases, Approach or ARTCC talks to airplanes just passing by, but in this limited scenario, they shipped the Cessna to a nearby tower (Class D below 2700). The pilot called the tower and told them he was just passing by, and they approved the transition. Minutes later, the Cessna starting having some kind of problem and went down.

The tower controllers never saw it as they were focused on their airspace. In this tower, all aircraft that call the tower have their call signs written down on paper to assist as a memory aid for the controllers. This controller wrote it down, but took several minutes to get back to it. By the time they did, the Cessna was down. They assumed he went back to Approach, but didn’t see anything on the radar, so nothing was thought of it. Then 15 minutes later, Approach called and asked if the Cessna had landed there. They responded, “Negative. We thought he went back to Approach and continued.” The approach controller responded, “He never came back and we don’t see him on radar.”

After another five minutes of scrambling to figure out where this airplane had gone, the tower supervisor looked up the call sign on FlightAware and saw its flight track descend to the ground near their airspace. With all the back and forth the emergency checklist was long delayed. It was a whopping 15 minutes after they realized the aircraft was missing.

The occupants of the Cessna did not survive to the time emergency responders arrived. They both made it out of the plane but perished. The facilities involved got a report from responders stating the pilots could have been saved if help had arrived earlier. All said and done, several facilities have been going though some audits to assess response time statistics and prevent this from happening again.

From the description I heard, I’d surmise there was a failure on several parts. In this case the pilot never told ATC there was a problem, and the controllers forgot about him. Why was this aircraft switched to a tower well below his altitude? Did Tower feel that since the airplane was not in their airspace, they were not responsible? Why did it take over 20 minutes to send out help? There are so many questions that arise here.

I’m very interested in reading the final NTSB report. Lives were lost due to lack of communication and positive control. If the pilot had simply made just one transmission to ATC saying, “Mayday,” or “Oh, crap,” or something, ATC definitely would have gotten the hint and those people might be alive today. —EH

There are between one and 20 forms that should be filled out. The number varies by facility type, airspace, what aircraft/vehicle is involved, etc. These are all incident forms that need to be filled out ASAP while fresh in everyone’s mind. They have all the details on them including weather observations, recent PIREPs, traffic workload, etc. It may seem like a lot of unnecessary info, but if bad goes to worse, these little details go into the investigations by NTSB and help determine what went wrong and the best way to move forward.

Secondary Crash Phone

All that initial flurry of activity is complete. Now what? We’re going to assume that you declared but didn’t make it to the airport. It varies by exactly where you declare, but if near an airport that has “Aircraft Rescue and Firefighting” (ARFF), the Tower is notified to ring the crash phone. If you are out in the middle of nowhere, the approach control or the ARTCC you’re talking to will run their checklist similar to above, and those will alert higher authorities. It starts with ARFF (if applicable) then moves out to the closest rescue station. If there are none, it goes to the ARTCC Ops desk and they get in touch with Search and Rescue (sometimes a Civil Air Patrol airplane) to dispatch immediately. Keep in mind that safety comes first. If it’s bad weather, they won’t send another aircraft out to find a downed one; initial efforts would be groundbased only. After all is done with search and rescue, the Regional Operations Center (ROC) is notified. This adds exponential resources to assist if needed. The ROC works with many other entities such as NTSB and FSDO, who are at the top of the notification list immediately. After that, the original CIC or supervisor then notifies the Domestic Events Network (DEN).

The DEN is an interagency teleconferencing system that allows certain agencies to communicate and coordinate their response to violations of restricted airspace. It was established just after 9/11 in response to the attacks.

To break it down, it’s basically an open line that any ATC facility and a few other agencies can call and use to coordinate/communicate things happening across the country in real time. One thing that will put facilities on the line is if someone squawks 7500. Not only would my radar make a loud buzzing noise, they would hear it all the way up in DC. If ATC determines it’s real, the closest fighters will be airborne.

The DEN is also used for certain VIP movement. So, from beginning with one controller who heard the pilot say something, within 10-15 minutes, up to 50 people know about an emergency. If that emergency turns into an accident, that number goes up to the hundreds. FSDO and NTSB are at the top of that list because if the worst happens, they need to be first on scene right behind fire/rescue. Immediately after an accident or crash is when most critical evidence is present.

After the DEN is notified, the CIC, Supervisor, or Air Traffic Manager (ATM) continues along the list with law enforcement or a military authority if needed. Then the list goes to the

ATM and supervisors of the facility if they weren’t in the building. Next, the local ATC union president is notified. It may seem redundant, but the first thing management does is notify up their chain of command, and sometimes repeat the calls that should have already been made by the CIC or first person in charge. It’s similar to when an accident happens and everyone calls 911 for the same thing.

If the crash happened on or near the airport, the airport operations supervisor is notified, who then notifies airport authority and manager. Finally, if needed, the ATM will notify the Washington Ops Center. That call typically isn’t made unless another 9/11 or anything involving Air Force 1 happens.

Final Outcome

As you can see, there are significant resources for not just emergencies, but accidents. Walking away alive is a variable highly determined by the actions of the pilot before the crash. Of course, I am a firm believer in aviate, navigate, communicate. However, I also believe that “communicate” part is a must and should be included as soon as possible. This is also why I highly encourage filing IFR whenever possible, or at least utilizing flight following—you’ll always have someone to talk to.

In addition to your standard required ELT, tying your GPS to your ELT (or having an ELT with embedded GPS) will greatly assist in locating you, whether it is a personal beacon or installed in the aircraft. Sure, those things can be pricey, but any pilot knows that flying is not cheap. You might spend $100K on an airplane; would you up that to $101K to increase your chances of being found if the worst happened? It’s clear that the sooner someone knows about your distress, the sooner help will arrive.

My goal here is to change the minds of some pilots who don’t talk to ATC at all or are not very helpful with exchanging information. Since most professional pilots are flying on IFR flight plans, talking to ATC is not an issue. Where does that leave the rest of us? You aren’t taught “aviate, navigate, communicate” just to throw the last part out. Help us help you. Talk to us. You might even find that most of us are friendly and helpful.

Excellent article.

Thank you.

“I’m declaring an emergency,” said the Potomac Approach controller, in a sweet, calm voice. My reflexive demurral was quickly stifled, to be replaced with a “thanks.”

“Say intentions?”

No, Ma’am, I didn’t want to take my jammed full-nose-up trim Mooney 231 back into tiny College Park. But wait, there, at 12:00, not ten miles away was the longest, widest runway this side of Cape Canaveral.

“No, sorry, Andrews is not an option,” she said.

So. Emergency declared. Airplane barely controllable with two of us pushing hard against the mechanical jam. Next option is at least 45 minutes away with the power low and flaps deployed. We are both elderly, and arms were soon aching. Holding altitude was increasingly tough. At least we had very good vfr.

Question is, what is pilot’s prerogative here? Andrews AFB was an easy, safe out. No chance, she said, emergency or no.

Many second-guessers told me the controller, bless her, was mistaken, and I could have, should have, insisted on that beautiful military runway. Imagining this sweet granny and grandpa spread-eagled on the ramp, surrounded by twitchy MPs with machine guns, wondering what would be involved in disassembling my bird for removal, I didn’t argue..

As it turned out, we finally made it, more or less, to a good civilian airport, but what an ordeal! Should I have asked what part of the E-word wasn’t clear?

Amelia: yes. Land anyhow. A few years ago the AOPA Air Safety Foundation put together a very good true event after accident video. In that event the pilot allowed the AFB controller to wave him off. He died for being too compliant. I’m glad you survived.

So far I’ve only had one emergency (declared by the ATC controller when I told him I had a VERY rough engine and was making a 180 for the closest runway with lights — it was a very black night). Before my could roll out on heading I informed him my engine seized. I was very busy for the next 8 minutes and 45 seconds. The controller declared “E”, probably while I was still in the turn and before the plane became a glider.