We all have a different way to go about our flight planning, but most of it is along the lines of where to go, how high, how much fuel, weight and balance, etc. You factor it all into the plan, but at some point you’ll add that “X” for some bad weather and a re-route. Maybe the weather is fine where you are departing but not good where you are going, or vice versa. Depending on the mission, what are your options? It all comes down to a “go/no-go” on what you’re comfortable doing and not doing. This is the typical process regardless of whether you’re filing VFR or IFR.

On the ATC side of things, we don’t pre-flight, but we do pre-plan. When it comes down to managing large amounts of traffic, weather, and many other things, there is the Traffic Management Unit (TMU). TMU sees the bigger picture from weather radar, PIREPS, and other tools to help them determine if you should be flying through a certain area. They also work with controllers and other upper-level agencies to determine cutoffs on arrivals or ground stops. They look at all these factors and make a determination whether an airplane can, in fact, go in a particular direction. Subsequently, all the facilities below (like a VFR tower) follow the leader.

Flight Plan Tetris…

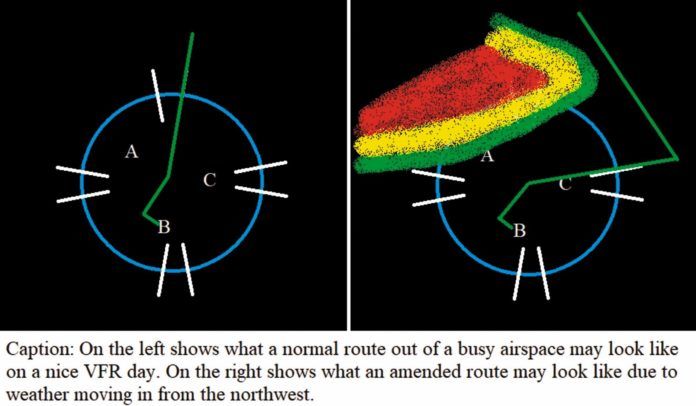

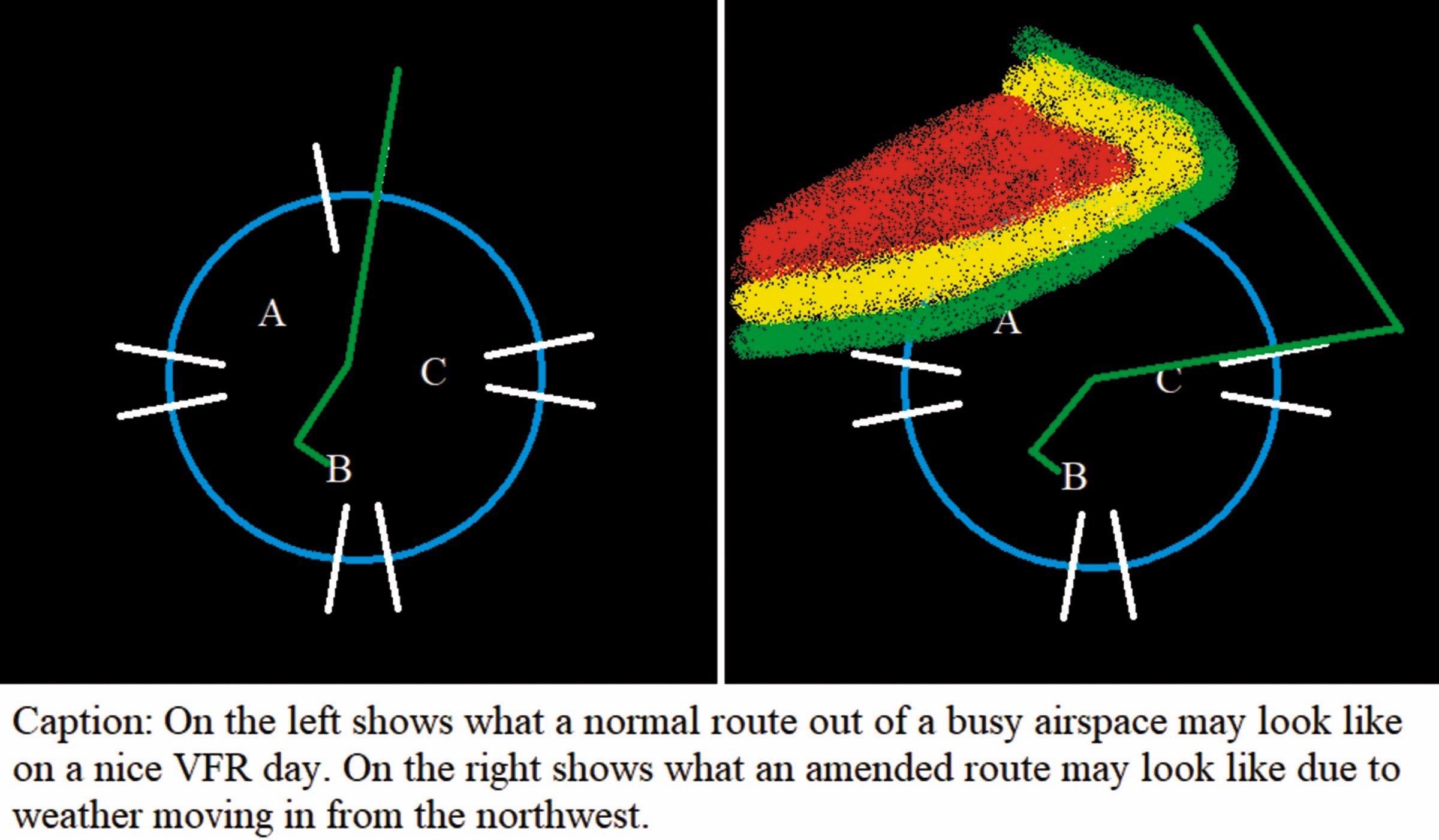

When it comes to flight planning, there are literally 360 different ways you can go. However, when weather sets in, your available routes fall away. Instead of going north, you might have to go west then north, or south then west, then north. It can quickly get complicated.

However, in some parts of the country ATC has a program specifically made for weather avoidance. Some facilities call it SWAPs (Severe Weather Avoidance Procedures); others don’t have a name and just work traffic a little differently—or the airport stops. The main intent is to keep a large amount of traffic moving safely despite that big thunderstorm in the way. If a pilot is familiar enough with the area, he might be able to anticipate the coming reroutes, but unless he is familiar with local ATC procedures, he won’t be able to account for every variable. There are a few things pilots can do, but before you do them you should consider if it helps or hurts ATC.

On a normal day, you go through all your flight planning and file like always. No bad weather to mess with. You file, get your clearance for the route that the system gives you. Nothing out of order—you get radar vectors to depart, might follow a departure procedure to a route (airway, direct, or a combination) possibly to an arrival into your destination. Piece of cake, right?

Okay, let’s add Mother Nature into your equation. There is a front approaching your departure airport from the north, but you need to go north. Let’s say you file direct and take what you get. What you get this day is a route 50 miles east, then north, a much longer route for which you don’t have the fuel. What do you do?

You only really have a couple options. Wait until the front/storm passes or take the amended route. But consider that the amended route is not necessarily as limited as it first seems. You might get up and over the weather on the amended route and tell ATC you’re on top, with a “Roger, proceed direct” reply. Of course, you can’t count on this every time.

On ATCs side, that front has potentially closed the departure and arrival gates to the north. Arrivals into the area from that direction are routed around to the east or to the west. Since weather moves relatively slowly compared to your airplane, ATC’s use of such procedures help maximize the use of the airspace and airports. If the front is only on one side of the airspace, ATC will not stop the entire area (depending on size). Instead, they will continue to bring in and land/depart airplanes on the unaffected portion up until the last minute.

Now keep in mind that we are not assuming low clouds and some mist. I’m talking about don’t-fly-through-that-thunderstorm weather. As the weather moves through, the airplanes will be brought out of holding or released from the previously affected area. The best way to imagine this is to think of your hand as a thunderstorm and a bucket of water being usable airspace. Put your hand in a bucket of water, then move it from one side to the other quickly. For a brief time, there will not be any water where your hand was, but as soon as it moves, the water flows back in. The only time the entire airspace might close is if the storm encompasses the entire airspace and it’s just not safe.

What Can I Do About It?

We originally assumed that the pilot in the above scenario filed direct. Well maybe you’re thinking that the amended route doesn’t work with your fuel reserves, so you consider individual points to cut some time off the route. You calculate that you can potentially save 30 minutes of flight time, so you take a chance and file it. It comes back with the same DP and route that you got when filing direct.

I can’t tell you how many duplicate flight plans I deal with when weather moves in. (Duplicate = same aircraft, same departure, same destination. Route might be different.) You don’t understand why you got the same route since your second route with different points should work. If you got the same route twice, it’s basically the system not allowing it as it could add additional workload on ATC.

It’s accurately said that when weather moves in, Radar/Center controllers earn their pay. Having all pilots fly the same departure/arrival routes based on where they enter or exit, is how the airspace system is designed. This reduces controller workload and makes everything easier on everyone while maximizing airspace efficiency. Having one airplane try to “get around the system” might help you, but hurt the overall system.

Another way some pilots like to try to “get around the weather” especially at tower-controlled fields is to depart VFR and pick up IFR in the air. Maybe that weather is coming but it’s not there yet, and you see a clear path in another direction. Although legal, I personally do not recommend doing this for multiple reasons, mainly because I have seen it turn into an unnecessary emergency. (See the sidebar.)

I will say that when ATC deals with weather and flow restrictions in or out of an airport, it is not easy to add the VFR guy to the mix when the IFR traffic has been stacked perfectly and many of those have been waiting some time. It’s the equivalent of cutting in line. Also keep in mind that workload and airspace permitting, ATC need not give you an IFR clearance right away. Although rare, if it is safer for the controller to tell you, “Unable IFR. Maintain VFR,” they won’t hesitate to do just that.

In some cases, your procedures might require you to file an IFR flight plan. (Company rules, personal preference, etc.) If you’re flying anything that cruises above FL180, you’ll absolutely be filing. If not, it might be easier for you to not file and go VFR, maybe with flight following for the entire flight. Minus all the intricacies of airplane efficiency, if this works safely for you, go for it.

Musical Airplanes

Once upon a stormy day, I was working clearance delivery with plenty of departure strips. I had about 20 airplanes all trying to get out and about half were filed to go south into the bad weather. It’s always fun trying to coordinate weather reroutes. So out of the mix, I had about five call me, one right after the other, looking for their clearance. Three of these were reroutes, so I started to rattle off clearances to the ones that did not have an alternate route, and called TMU for a reroute on the others.

After the first two clearances, I started to receive the amended routes for my last three. That’s when it got busy. First clearance was no problem. Second, the pilot had many questions, so I told him to standby and read the third one off before returning. All these pilots were trying to depart before the weather moved in, so I was working as fast and efficiently as I could.

I went back to the second pilot and got some odd questions. “Do you know when the weather is moving in? Can I get a different route? Can I go VFR?” I responded, “Well I’m not a weather expert, but the weather looks like it could be here within the hour. What route are you looking for and where are you trying to go VFR? Same place?” There was a pause, then he responded, “I’m trying to get off the ground and get to (airport) ASAP. Are there any other routes?”

As I’d already issued him an amended route (his original took him right through a 40-mile-wide thunderstorm), I responded, “Sir I already gave you what I received for an amended route. The original took you through bad weather.” I don’t think he liked my answers, but there is only so much I can say or recommend. He replied with, “So there is no other way or more direct route?” I said, “Not at the moment, Sir. There are 2 others trying to go to the same place who are holding short of the runway now. They have been waiting about 15 minutes.” Last thing I heard was, “Okay fine…” I passed the strip to the ground controller and that was the last I heard of it … until two hours later.

Coming back from a break, I got asked, “Hey did you give N12345 this clearance? Did he take it?” I said, “Yes, he took it but didn’t like it. He was trying to find a way to get around the weather and go more direct but I told him that’s where most of the bad weather was. Why?” The supervisor told me that he had departed VFR and tried to pick up his amended route in the air, but was initially denied. The pilot didn’t like that, so started flying his route anyway, and climbed above FL180. The controller he was talking to had to shuffle three other flights so he could radar identify him and gave him his IFR clearance.

Without being coordinated into the system, there was no space for him on the arrivals into the destination airport; he had the pleasure of holding for over an hour. By the time they had space, he was declaring a low fuel emergency. He did land safely, but the whole flight was put under a microscope. I can’t imagine that turned out too well for him. —EH

Get in Line

Let’s talk a bit about flow control. You might have heard of an EDCT (Expect Departure Clearance Time). EDCTs occur when a given route or part of one is traffic saturated—often due to weather—and can’t take additional aircraft without imposing some spacing. When you receive an EDCT, local ATC must (usually) clear you for takeoff within five minutes of that time.

When there are multiple airplanes with a SWAP clearance, getting them out is similar to having an EDCT. You go to the runway first, there are only a few airplanes going out the same departure gate as you, and there are five other airports in the area with airplanes ready to go as well. ATC does their best to get you in line, but that line of departures can be a yo-yo sometimes. The guy in front of you on the same route was waiting 20 minutes but you only waited five. It’s all case by case.

As soon as weather is no longer a factor, you can’t expect the Tower to clear one right after the other—minimum IFR separation still applies. There are some times you will see an airplane depart in front of you while you were waiting the longest. I’ve been questioned on frequency more than once, “Hey Tower why is that guy going first?” The most common answer I give is if it was someone on a different route that was not amended, or it was a MEDEVAC flight. One thing I like to do is remind the pilots I haven’t forgot about them. Priorities are somewhat dynamic.

Cleared for the Options

Okay, so knowing what’s happening when there’s weather might not soften the impact to you, but it might help dissipate your frustration. Just know your options and how they affect everyone else. When flight planning around weather, make conservative, safe decisions, and be careful when considering circumventing the procedures it’s taken ATC years to create and perfect so they can keep everyone moving. On those days, fuel efficiency might not be the best, but safety still will be. If you are being rerouted, there is an extremely high probability that several others will be as well, and it’s ATC’s goal to get everybody there safely.

Even though it only takes Elim Hawkins a few minutes to drive to work, that time can double if a single road is closed. He understands the pain a weather-related reroute can deliver.