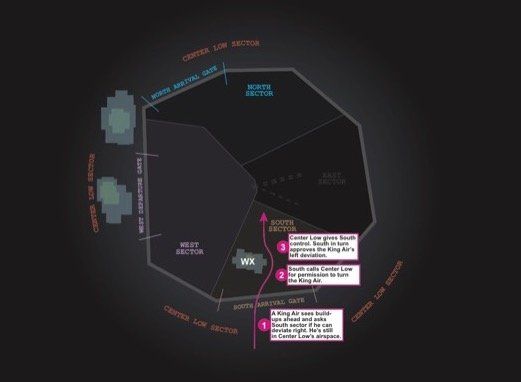

The King Air was descending out of 15,000 feet when he checked in with me. My radar scope was already peppered with growing blue and green areas of moderate and heavy precipitation, and I was buckling down for what was sure to be a crazy session. Storm season was here with a vengeance.

“We’ve got some buildups ahead,” the King Air said. “We’re going to need to deviate right.” My scope showed nothing in his path, but, then again, our radars only show precipitation. Rain. Snow. Hail. We don’t depict clouds, turbulence, or wind shear. There was something developing in his path, and he wasn’t liking it. Whether I could see it or not was irrelevant. He needed a turn.

We controllers are trained to do everything in our power to help pilots stay out of the worst of the weather. The atmosphere’s an unpredictable beast. NTSB records are full of accidents where pilots ran out of luck in nasty weather. No controller wants to participate in such a tragedy, either by action or by omission.

Of course, I wanted to give the King Air the deviation right he needed. Providing weather information and guidance around potentially dangerous conditions is a huge part of my job. What stood in the way of that? Coordination. Depending on where an aircraft is and where it’s going, getting a pilot what he wants can demand legwork, accurate communication, and time.

Coordination Concerns

ATC facilities adjacent to one another share more than just airspace boundaries. They have letters of agreement (LOA) that govern how and where aircraft cross those lines. Included within are definitions for arrival and departure “gates,” and the expected altitudes and routings for aircraft to transition those gates.

LOAs have sections specifying how much control a facility has over an inbound aircraft before it hits their boundary. For instance, if the King Air had come in from our West gate, our LOA with our overlying center states that, once he gets within five miles of my boundary, I would have control to turn him up to 30 degrees left and right. Our East gate grants me turns to the north and control for descent.

However, he was coming in our South gate. There, I owned airspace 12,000 feet and below. Once he descended into my jurisdiction, I could allow him to turn. Until he did, though, the LOA only granted me control for left turns, not right, as he needed. The time he took to descend the 3000 feet into my airspace might put him in the thick of whatever he saw. I didn’t want to wait that long.

I punched the landline to our overlying center’s low altitude sector. “Center Low, Approach South, ApReq.” That last word—short for approval request—means I’m asking for their permission to do something that’s not permitted in our LOA. In this case, it’s turn the King Air right before he hits my airspace.

The center controller answered. “Center Low.” Controllers don’t have time to be chatty; we’re terse by necessity. By announcing who he is, he’s saying, “I’m listening. What do you need?”

I said, “Request control, King Air 123AB, deviating around weather.” I’m asking if I can take complete control over this King Air—forget all turn, speed, or altitude gate restrictions in the LOA—and allow the aircraft to weave around the weather in whatever manner he sees fit. I also technically don’t have to throw in the “deviating around weather” reason. The center controller likely sees that weather on his scope too. However, by saying it, it’s a heads up that any aircraft arriving after the King Air may also be deviating in that area.

“Approved as requested,” Center Low says. He and I each state each other’s operating initials—that’s how controllers hang up landline calls—and I get back to the King Air. “King Air 3AB, deviations right of course approved. When able, fly heading 360 and advise.”

The King Air ducked right. A few minutes later, he told me he was headed northbound, and continued without incident. By telling me well in advance, he’d given me plenty of time to coordinate for him. Many times, pilots wait until the last second, leaving controllers scrambling as a pilot hurtles into bad weather.

Big Picture Balancing Act

In the situation above, the King Air’s requested right turn didn’t have any significant impact on other traffic or other controllers. That’s not always the case. A pilot’s well-meaning, requested solution may actually cause tremendous complications if controllers approve it without thinking about overall traffic flow. We must keep the big picture in mind and quickly think up alternative options.

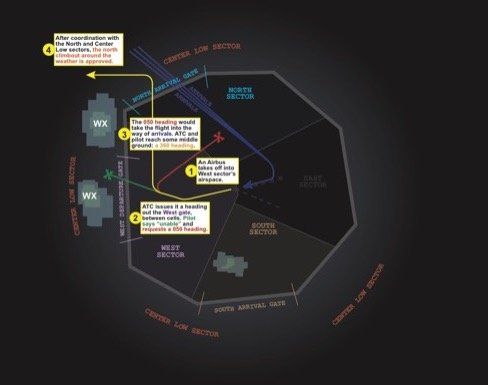

Later that day, I was working our West sector. An Airbus A320 departed, filed westbound. Two large cells of precipitation loomed outside the West departure gate. I assigned the aircraft a 300 heading aimed at a 15 mile gap between those cells, and told him the plan.

The Airbus crew balked. “We need a 050 heading.” This threw me for a second. Sure, yes, a 050 would indeed keep them fully away from the precip. However, it was basically a course reversal that would drive him into the descent paths from one of our main arrival gates, North Gate. Having a weather-deviating jet climbing in the face of descending arrivals had “potential disaster” scrawled all over it.

Instead of the 050 heading, I asked the Airbus crew, “Can you accept a 360 heading?” That would keep the weather off his left. A moment passed before they responded. “Yeah, that’ll work great,” the pilot said. I assigned him the 360 heading.

Through a Neighbor’s Yard

Alright, we’d agreed on a new heading. In-house coordination was next. The 360 heading would soon have him clipping our North sector controller’s airspace. “North, West, point out.” A point out means I’m going to be working and talking my aircraft through the airspace he owns. “North,” my friend answered. “Point out, Flight 654, northbound, climbing to 12,000. I’ll be giving Center control.”

“Point out approved.” North permitted the Airbus into his space under my control. He also accepted responsibility for missing them with his other traffic. Normally, he would immediately descend his arrivals. Now, he’ll keep them high until they passed my traffic.

Center was expecting that Airbus via the West gate, per our LOA, not North. I hit the landline again. “Center Low, West, ApReq.” When he answered, I continued, “ApReq, Flight 654 on a 360 heading, climbing to 12,000. Your control.”

Like he did earlier for me with the King Air, I was offering Center Low full control to maneuver the aircraft as he needed. He was doing the pilots and me a favor. I’d give him all the leeway I could.

Center Low approved it. I switched the Airbus to him. They flew around the weather, and, once they got north of it, Center Low turned them west into his space. North had to leave a couple of arrivals high for a few extra miles, but they still had plenty of time to get down. All in all, it worked out pretty well.

Trees for the Forest

Of course, controllers can’t only worry about general traffic flow. Deviations might at times be delayed, adjusted, or even outright denied by ATC due to traffic in the immediate vicinity.

One stormy afternoon, an IFR Piper Saratoga departed a satellite airport. I’d stopped him at 2000 feet; he was crossing underneath our main airport’s airliner departures. In another five miles, I’d be able to start climbing him.

The Saratoga suddenly requested a climb. He was getting knocked around by turbulence in the cloud bases. Unfortunately, there was nothing I could do at that moment. Passing 1000 feet directly over him—my minimum vertical separation—were a string of climbing airliners. I couldn’t bend the jets away from him, as I had another line of descending jets ten miles west of them. It would be an impromptu air show.

“Unable climb,” I said, “due to traffic passing above you. Expect higher in five miles.” This situation illustrates why FAR 91.123 explicitly states that pilots can deviate from ATC instructions in an emergency. I could not legally climb that Saratoga without busting my minimum 1000 foot separation between IFR aircraft. He couldn’t leave my 2000 altitude assignment under normal circumstances.

What if he was experiencing a “distress or urgency condition”—the definition of an emergency in the Pilot/Controller Glossary? Perhaps the turbulence got so violent he’d hit his head on the ceiling and was struggling to control his aircraft. Well, then he could do what needed doing: deviate and climb without ATC authorization. It was unlikely anyone would fault him or me for that.

However, there is one very important part of 91.123 that must be followed in such an event: “(c) Each pilot in command who, in an emergency… deviates from an ATC clearance or instruction shall notify ATC of that deviation as soon as possible.” Had he climbed, he would’ve had to tell me, so I could pry other aircraft away from him before they became a collision factor.

Fortunately, the Saratoga pilot was able to tough it out for those five miles and then got his climb into smoother air. Weather deviations aren’t fun for either side of the frequency, especially when either party’s hands are momentarily tied. Flexibility, good judgment, and patience are the order of the day.

Talk the Talk

Few things disrupt orderly air traffic control quite like weather. To help, there’s set phraseology to help pilots communicate their needs, and convey how much deviation leeway controllers can give.

ATC: “Area of [PRECIPITATION INTENSITY] precipitation, [CLOCK POSITION], [DISTANCE FROM YOU]. Area is [DEPTH] miles in diameter.” That’s the basic weather call. Our radar displays precipitation intensity as light, moderate, heavy, and extreme. The clock position and distance get you looking in the right direction. The “miles in diameter” is the precipitation’s horizontal depth.

Pilot: “Request deviation [NUMBER OF DEGREES] to the [LEFT/RIGHT].” You want to skirt around what you’re seeing. You can say this many ways, but the important elements are the direction of the deviation, and, if you can figure it out, how many degrees you need to turn. “Request deviation left of course, 10 degrees.” Alternately, “Request to deviate 10 degrees left.”

ATC: “Deviations to the [LEFT/RIGHT] approved. No further [LEFT/RIGHT] than [HEADING].” You need a turn? No problem. Often, we’ll give you more than you want just for padding. However, we may not initially let you go too far off course due to traffic or airspace. “Deviations to the left approved. No further left than heading 180.” Do you need more than what we’re allowing? Let us know so we can coordinate or vector other traffic out of the way.

ATC: “When able, proceed direct [FIX]/fly heading [HEADING] and advise.” You likely won’t be deviating forever. Controllers need to know when you’re done deviating and are back on course.

Pilot: “Deviation complete. We are direct [FIX]/turning to [HEADING] now.” This is almost a pilot report. We know the chunk of air you’re flying through has acceptable conditions. This is handy information for other aircraft in trail that may be trying to fly the same path.

ATC: “Fly heading [HEADING]. Vector around precipitation.” ATC often takes preemptive action. Issuing an early, off-course vector that cleanly steers the airplane away from a storm’s vicinity is far better than letting you get too close and needing to deviate at the last second.

If your view out the windshield looks better than what the controller is describing, feel free to say that you can take your original course. Our scopes are two dimensional. We have no idea how high the precipitation actually goes. We’ll just keep vectoring around it until we get a pilot report. However, you might be well above it already and don’t need a deviation.

ATC and Pilot: “[PLAIN ENGLISH].” Eventually, there comes a point where the weather phraseology just becomes cumbersome. Sometimes, it’s best just to throw it out the window and talk out options and actions in everyday language. Such an exchange may go as follows between ATC and an aircraft that was racing towards a gap between two cells.

ATC: “N123AB, it looks like that gap 20 miles ahead of you is closing up with heavy precipitation.”

Pilot: “Roger, Approach. Can I go west towards [NAVAID], and then cut north towards [AIRPORT]?”

ATC: “That’ll work. Cleared direct [NAVAID], then direct [AIRPORT]. You may need to deviate about five miles west of [NAVAID] before turning north, but we’ll keep an eye on the precip for you.”

Pilot: “Direct [NAVAID], direct [AIRPORT]. I’ll be looking and wait for your call.”—TK

Tarrance Kramer prefers nice, beautiful days where he never has to say the words, “Deviation approved.”