You’re eager for your day trip to meet the gang and head to East Lansing, Michigan for a Spartans football game—provided you can get yourself to Tecumseh, southeast of Michigan State University. No big deal; it’s less than two hours’ flight from your home base and you’re in your trusty Cessna 182. So far so good, until you actually see what’s in store for you.

Welcome to Tecumseh

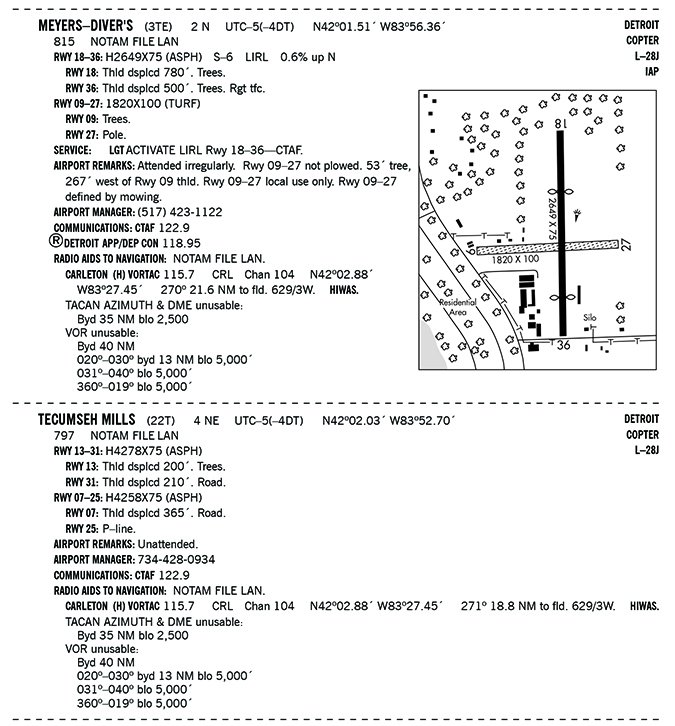

Tecumseh has just one airport offering an IFR approach, Meyers-Diver’s Airport. And it seems pretty basic in the amenities, but you won’t need much as your buddy will pick you up in his Hummer. Plus, 3TE is close enough to Detroit to advertise the SPRTN Three arrival via the DXO VOR to join an approach from the north, so you can expect a convenient, predictable route with lots of nice alternates.

You’ve never been to 3TE, so you dutifully start to “become familiar with all available information concerning that flight,” per 14 CFR 91.103. There is indeed just one IAP, the VOR or GPS-A. Right away you see that the airport sketch on the chart is, well, sketchy. You note with some optimism that there do not appear to be any worrisome marked obstacles close to the airport—another plus.

Then you see that Runway 18/36 is 2649 feet long, and both ends have the link symbols indicating displaced thresholds. You make a mental note to look into that. The sketch does show another runway—always nice to have—but 9/27 is a mere 1820 feet long and is not paved. Then you notice that the GPS-A approach 269-degree final course is lined up with Runway 27. It’s also a clear 5.0 NM from the intermediate fix, WAYNN, to the final fix, GERRI, and another 5.0 NM to the runway.

Despite your initial reluctance to consider it, you can’t help but wonder: Is there any reason to explore a straight-in for 27, or do you stick to 36 and take the longer of the short runways, winds be damned? You make another mental note to revisit that.

Just A Windsock

Now, back to the approach that, like the airport, definitely has a Spartan theme going for it. The top briefing boxes for runway landing distance and touchdown zone elevation are N/A, so all you get is the field elevation, 815 feet. The missed approach calls for a flight back to WAYNN for a hold using the course reversal. Circling minimums will be 1420 feet, about 600 feet AGL. As long as you’re in nothing bigger than a light piston aircraft, this is all pretty straightforward—until you’re ready to land.

Conditions on departure day have you looking mighty closely at those runways. A cold front that passed through Michigan left broken ceilings at 1800 feet and gusty winds from the northwest. How will you update airport conditions along the way? On the approach chart, you see a bare-bones frequency strip listing Detroit Approach and a CTAF. That’s it, no AWOS or ASOS.

This means you’ll want the Chart Supplement so you can scrounge up all the information you can. You confirm that Tecumseh lacks any weather reporting, save a windsock on the east side. (At least it’s lighted.) You’ll need to check stations at nearby airports: Ann Arbor to the northeast and Adrian to the southwest. Both are reporting marginal VFR with winds from 310 degrees at 18 knots, gusting to 24 knots.

The 27 Option

The Chart Supplement says that Runway 27 is “defined by mowing,” as if to confirm it’s grass. Landing straight in on Runway 27 avoids a circle-to-land maneuver with a lot of wind. You’re also reducing the gusting crosswind component to 15 knots (which happens to be the Cessna’s maximum demonstrated crosswind component.)

Disadvantages? The most obvious is the runway length. Weather conditions notwithstanding, would you land with 1820 feet of space? If you haven’t had to ask this question for a while, it might be time to get refreshed on your aircraft landing performance. Even if you’ve pledged never to choose runways less than 3000 feet long, you should still be familiar with required landing distance and anything you could do to reduce that. In fact, 91.103 notes that “takeoff and landing distance data” should be among the factors you’re familiar with.

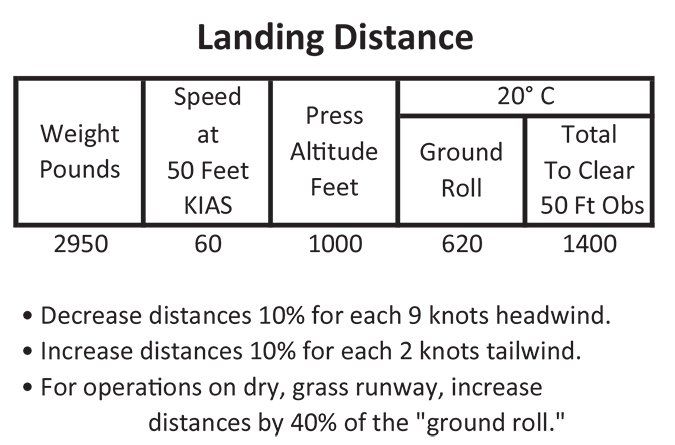

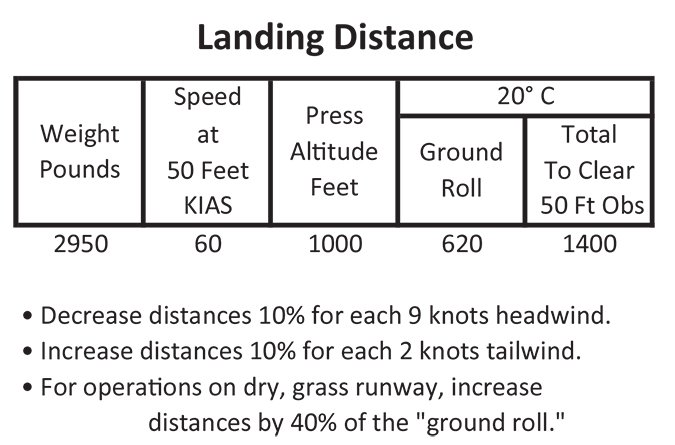

Of course, the 182 has a good reputation for adeptly handling short and unpaved runways, but you haven’t handled those yourself in a few years. The Landing Distance Table in the POH gives you a starting point. There’s a short-field table that accounts for full flaps at full gross weight, 2950 pounds, landing on dry grass. You’ll be a lot lighter coming in at about 2500 pounds, and there are no obstacles for this runway save an obscure note in the Chart Supplement about a “pole.” So you use the no-obstacle ground roll on the table.

There is standard pressure on this day and a temperature of 20 degrees C. Round up to a 1,000-foot pressure altitude and you have 620 feet. That’s roughly one-third of Runway 27, which seems to be reasonable. Based on the notes accounting for headwind component, you can even knock off a few more feet for the headwind component of four knots for a best-case scenario of about 590 feet.

But wait; there’s more! The table also calls for a 40 percent increase for a dry grass runway, bringing the 24-knot gust landing to 824 feet. That’s less than half the 1820 feet provided, but what will your short-field, soft-field, gusty-crosswind landings be like? If you round up the landing calculation to a cool 1000 feet to account for the inevitable variables in landing technique, winds and such, you could be looking at using up more room than you’d want.

A Better (?) Option

At this point you’re leaning towards Runway 36, which is relatively long by comparison and you’d be dealing with just another 10 degrees of crosswind component. You can plan to fly west down the GPS-A, then jog over for a right base to 36 with plenty of cloud clearance. Again, there are no significant obstacles to worry about except for trees noted at the approach end. Backtracking on the landing performance table with a tiny increase in headwind component, you’re back to about 590 feet.

Just to make sure you’ve got the whole picture, you look up a description of 3TE and study an aerial photo to confirm it’s clear of obstacles. The threshold for 36 is displaced 500 feet, with white markings depicting as much. So for landing, you get an official 2149 feet if you include the 780-foot displacement at the other end for landing rollout. The photo also shows a turf parallel runway for 18/36 (another common feature at rural airports that are often not published in chart supplements.) Chalk this up for emergency use as you prefer a marked runway when breaking out of the clouds.

Now, you have all the required information and then some, and have considered your assessments of landing performance, your questionable ability to land in less than 1000 feet, and the likelihood of adequate weather to circle for landing. You decide that Runway 36 is your best bet to make it in on time, comfortably, and with runway to spare.

Back To Basics

While it’s nice not to have to worry about radio towers, crowds of traffic or a long taxi at a place like 3TE, an airport that’s as basic as this requires just as much time to prepare and sometimes even longer. With little to work with, strategic planning is just as essential as those times when the options are plentiful.

The lack of information also means you might need to go beyond the official information to sources like airport web sites and photos, and the POH to get “all available information,” especially when it’s sketchy in the details.

Elaine Kauh is a CFII in eastern Wisconsin. She is not a Michigan State fan, but cheers for another Big Ten team.