Like bad breath at a cocktail party, no one tells you you’ve got a problem; they just won’t want anything to do with you. Follow these tips and you’ll never be “that guy” on the radio.

In the film The King’s Speech, the future King George VI stammers and fumbles trying to start a nationally broadcast speech in front of a packed Wembley Stadium. With obligatory camera shots of the red “On Air” light blinking in mockery, the prince gives up and walks away from the microphone.

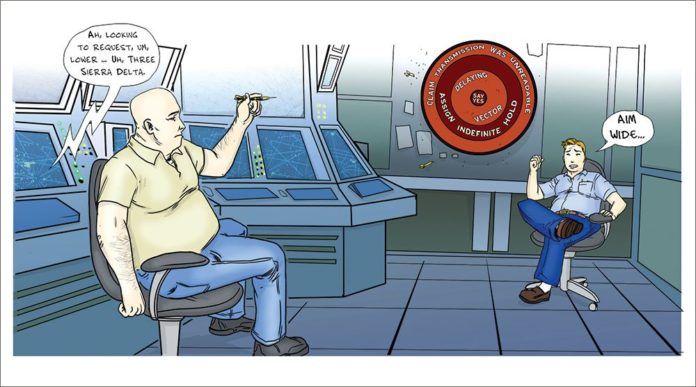

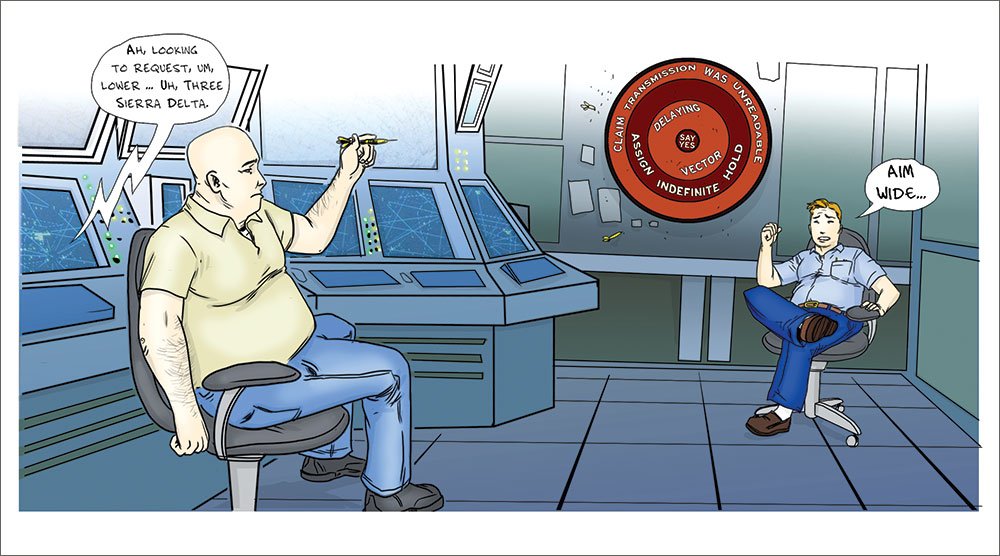

While it may seem overly dramatic, many pilots face similar trepidation when pressing the push-to-talk switch. Others suffer from the opposite malady, which I call “Overdubbed Movie Syndrome.” The hallmark of this syndrome is a moving mouth prior to any cohesive dialog being formed. All kinds of interesting vocal gymnastics and hopelessly non-standard phraseology come out instead.

Radio communications on air-traffic frequencies are not as standard as glossaries and training materials would have us believe. Yet it’s not really all that difficult to sound like a pro, even if you’re not flying nearly as much as you would like.

Tips For Hesitant

There are professional pilots and amateur pilots, but only professional controllers. If you let that intimidate you, worrying you’ll sound like a rookie asking for this different routing because you haven’t keyed the mic since last fall, then you’ll be like the future king and give up on even trying. It’s an understandable fear, but one that is instantly remediable.

Recite the following mantra: “Keep it simple.” Trite? Sure. Effective? Absolutely. The pilot-ATC communication relationship is kept on track by the wonderful concept of standard phraseology. Using as few words as possible, state your request using standard terms: “Gotham City Approach, Cessna Two Eight Tango requests pilot discretion descent to 5000.” That sure sounds better than “Aah … Approach, Two Eight Tango … ahh … can I get lower?”

When I hear this kind of call, I just imagine the controller thinking, “Well, by the looks of your Mode-C, you’ve already given yourself lower … and higher … and lower.” Sounding professional is a step toward being treated with respect—and getting your requests granted.

Don’t get me wrong when I say, “amateur.” Sure, it means anyone who isn’t making any money while they fly (insert regional-airline pilot joke of your choice here). The more relevant meaning describes how one conducts oneself as a pilot. I’ve known student pilots who conduct themselves with the utmost professionalism, all the while listening to “professional” pilots who sound like they shouldn’t be washing planes, much less flying them. I once read that professionalism is doing the right thing when no one is watching. On the radio, professionalism is saying the right thing no matter who is listening.

Spotting Hacks

You can spot a hack on frequency almost instantly. First, there’s the “I’m too cool for VHF” pilot trying to sound like Jack Nicholson with a frog in his throat. Moderate-to-severe non-standard radio phraseology is usually an accompanying symptom.

Another hack-tacular technique is when Conglomerate Express 545 answers ATC queries with “545.” Sure, there may be a dozen other aircraft in the area known as XYZ 545, but why bother differentiating yourself from them by stating your full call sign? You’re just so awesome that we should all know who you are.

At the risk of being too esoteric, I’ll call one style to avoid the Morris Albert Effect (this one extends to the controllers, too). For those of you fortunate enough to miss the 1970s, Morris Albert sang the cloying pop ballad “Feelings.” I should never be able to guess how you’re feeling by your transmission. Not happy about your sequence or the “Have a nice day” vector that ATC just gave you? Don’t get snotty. If you have an issue with a controller (or pilot), make a note of it and take it up later. Remember, tone of voice can carry as much weight as what you say.

You Don’t Say

I believe professionalism encompasses what you say as well as how you say it. We’ve all heard the pervasive “Any traffic in the area, please advise.” This is tempting when you’ve been dumped off just outside the marker with radar service abruptly terminated. You’re coming into a Class G airport without the benefit of monitoring the frequency (unless you’ve used a spare radio to do just that) and you’d like to get a picture of what’s going on before riding the ILS into the murk of the unknown.

Tempting though it may be, please don’t ever use this phrase. The AIM comes right out and says it in Paragraph 4-1-9 (g). I wonder if some pilots do it because they can’t be bothered with all that “monitoring the frequency” stuff.

Reporting your position is a good policy for other pilot’s situational awareness (but please include VFR terms, such as “VAPOR inbound on seven-mile final for Runway 23”). Besides, this is leading by example and is a better way to get the other pilots to simply report their position in the Marco Polo game way-it-works at uncontrolled airports. Besides, do I really need the student pilot—who’s nervously adding the last notch of flaps and trying to maintain airspeed—report that she’s six miles ahead of me? The only collision hazard she presents is at the FBO coffee maker.

Take this one for what it’s worth: The phrase “… is with you at …” has probably led to dozens of cases of carpal tunnel syndrome thanks to internet debates. Does it bother me if someone checks in and says, “Gotham City Approach, Jetprop Six Two Alpha is with you at 5000, direct Gotham”?

Not at all. I know what they mean, and so does the controller. However, it is a waste of bandwidth and strays from the Keep It Simple mantra. “Gotham City Approach, Jetprop Six Two Alpha, 5000, direct Gotham” is better. If you’re going to use up four syllables that aren’t part of standard radio phraseology, you might as well use them as you check in and say “Good afternoon.”

I’m going to pass on a request I know controllers appreciate. (I’m hoping they remember this when I’m a mile from the marker and they’re thinking of downgrading the reported RVR to 1600.) When you check in with the Approach handling your arrival, let them know you have the current ATIS at your destination. It might change before arrival, but it’s still good technique. If you’re going to a Class G airport, let them know you have the latest automated weather. They’re going to have to ask if you don’t tell them—trust me.

Yes, there will be days when cockpit duties preempt getting the ATIS early, but that’s the exception.

Kinder, Gentler Criticism

While you should have a plan when you transmit, and you should be well-versed in proper phraseology, don’t fear making a mistake or sounding like a newbie on the radio. We all have our moments, and sometimes a direct and primal statement can save the day.

One of the best ATC exchanges I ever heard was near Lake Winnipesaukee in New Hampshire between the trepidatious voice of a presumably young student pilot and Manchester Approach. He simply said, “Manchester Approach, Cessna Two Seven Five Seven Six, request … help.”

The controller was fantastic and quick on the draw, perhaps alerted by a VFR flight plan that he was dealing with a student on a solo cross-country. He quickly ID’d the aircraft and gave him his location and suggested heading. The relief in the pilot’s voice was palpable and I knew from the exchange that he was back on track. That pilot certainly kept it simple and wasn’t afraid to sound like a new guy, and it worked out great for him.

One afternoon years ago in my commuter-airline role, I was bouncing between two airports that were comfortably blanketed under a layer of advection fog that blended seamlessly into a thick, stratus goop. Even IFR, the legs were only 20 minutes long, culminating in an 1800 RVR approach at one end and 2400 RVR on the return—pretty standard fare for that gig.

Anyway, after about 14 single-pilot approaches in four hours, I started to get a little, shall we say, “intellectually challenged.” The ATIS was Lima and the clearance I had parroted seven times so far was direct BOGEY.

Sure enough, I keyed up that I was, “… at 2000, heading of 360, with BOGEY.” Without missing a beat, one of my coworkers, who was sequenced ahead of me into the same airport, chimed in over company frequency: “You better hope he doesn’t clear you direct Lima.” Fully aware that I lacked sufficient fuel for a clearance to Peru, the kind controller just issued my next vector and pretended as though nothing had happened.

I suppose radio technique can embrace the Japanese aesthetic of wabi-sabi, or “Beauty in Imperfection” (gross oversimplification alert). Mistakes will happen. That’s human nature. But fear of making mistakes should never affect your relationship with the push-to-talk switch.

Got Albert in a Can

Our friend Prince Albert eventually became King George VI. Thanks to the help of an eccentric speech therapist, he delivered a riveting speech on radio to a national audience at the dawn of the Second World War.

Most of us don’t need speech therapists, or to keep ATC riveted to the radio for that matter. We can build our confidence and skew the odds of getting our requests granted by sticking to these four simple rules: Keep it simple, keep it standard, don’t be a hack, and accept that when it all falls apart, just saying something clearly enough to get what you need is better than saying it like a pro.

Evan Cushing is a regional airline pilot and training supervisor for the ATR. He tries to get out enough to keep up his confidence on the air.